Andrew Jr, 1923-1944

A photo album as biography

Today marks the 80th anniversary of my father’s brother’s death during World War II. I’ll write more about the death itself for Memorial Day, but here I’d like to celebrate his life, which I only know through a photo album he left behind.

No one occupies more of the Olsen family archive than its missing member: Andrew Jr. My grandfather kept every scrap of his eldest son’s memorabilia— from his watches and his wings (posthumously awarded) to every handwritten gift card. A folder labeled Andrew Olsen Jr. still contains an itemized accounting of the funeral expenses as well paper slips for every payment to the quartermaster at the Citadel while Andrew Jr. was a student there. Hauntingly, Andrew Jr. seems to have shared this urge to save for posterity: while training as a pilot he forwarded his active duty notice to his mother with an uncharacteristically offhand note “Worth saving to look at after the war. Put in my album will you. Better than throwing away. Love, Andrew.”

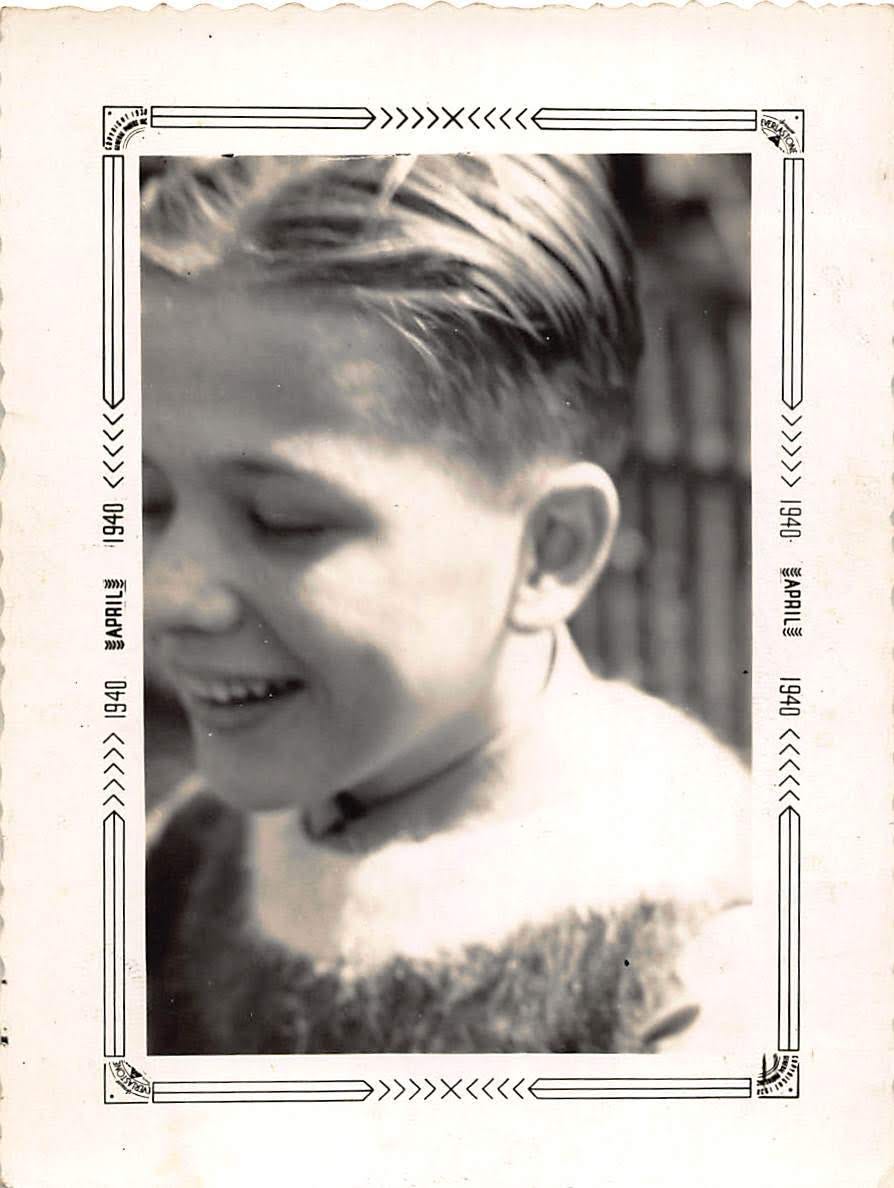

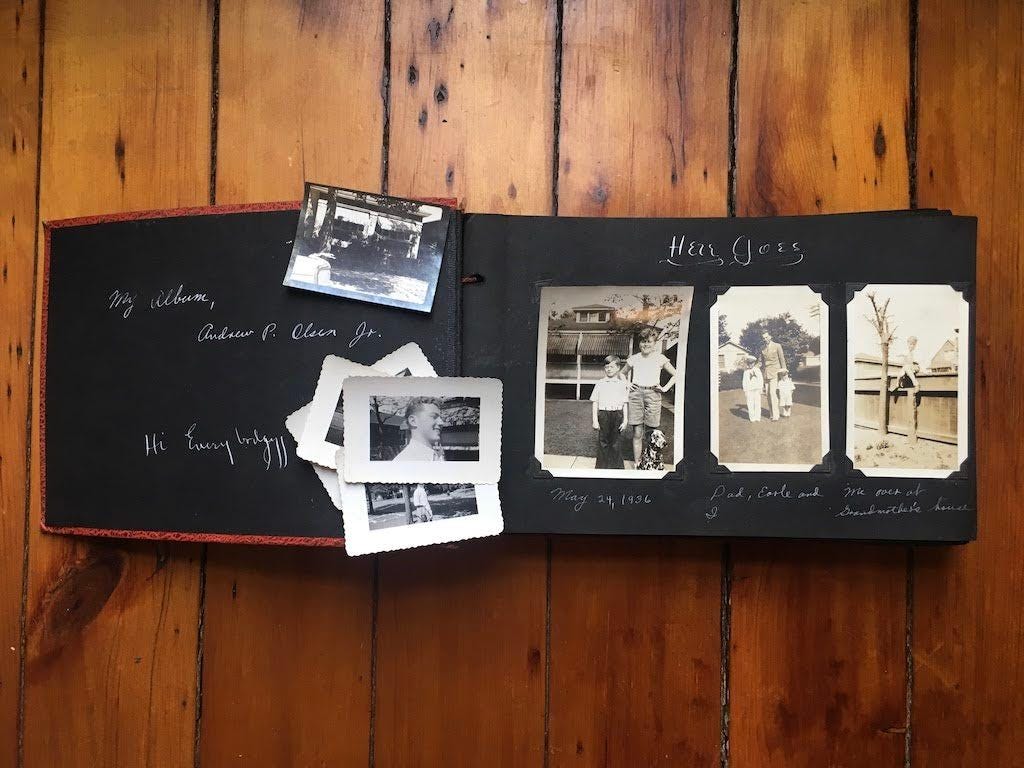

The album Andrew Jr. refers to was probably the elaborately detailed photo album he assembled when he graduated from high school in 1941. It has the quality of a yearbook but constructs a story of Andrew’s whole short life, starting with his birth, and virtually every photo is captioned. The first page announces “My album, Andrew P. Olsen Jr. Hi Everybodyyyy!!!” and opens with portraits of himself, his younger brother Earle, and their father Andrew Sr. The sequence is roughly chronological, with the first half devoted to dogs and summer vacations in Michigan, as well as a 1932 trip the extended family took to California.

Throughout the album, Andy Jr. appears as something of a joker: he captions photos at the beach with “Tarzan!” and includes goofy self-portraits as an FBI agent. But the album is creative too: that Tarzan image is traced with curvy lines to create an illusion of muscles. The muscles are even labelled “Muscles!” in more energetic script. He is the star of this show but, unlike other family albums, he names the individuals in the pictures and makes a few joking references that reveal something about them. He comments on his bare head and notes that his mother didn’t like him always wearing hats.

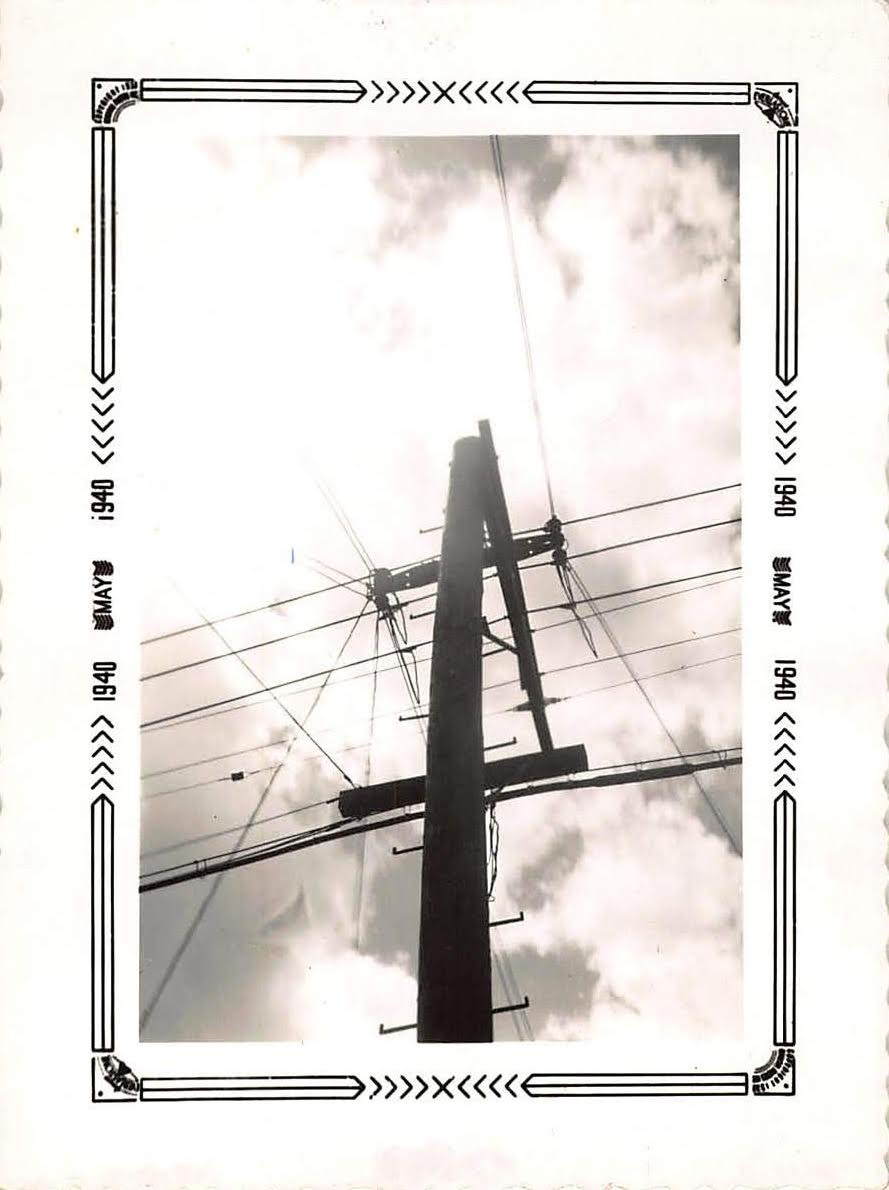

Over a few intensive months in 1940 the seventeen-year-old Andy experimented with still life shots. The prints have crimped edges and carefully document a vase of budding flowers, a grid of telephone wires, a globe and binoculars. The focus and lighting is uneven but he’s clearly experimenting with angles and composition.

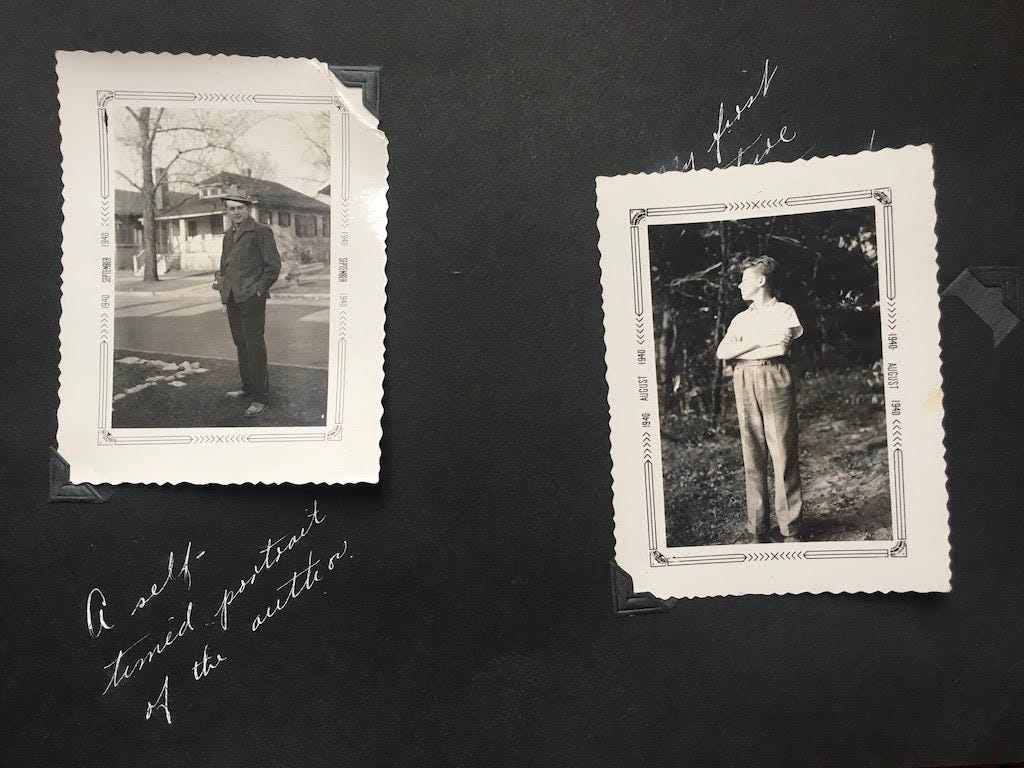

My father Earle, three years younger, is everywhere: mostly “me and Earle” but sometimes “Earle in action” running down the street or climbing over fences. It’s a new view of my father—as an energetic child—and it makes me wonder how much his life stalled and slowed with the loss of his older brother. Almost every page has a study of my father and as he grew older they were taken by Andy himself. One, stamped August, portrays my father at thirteen, arms crossed and head turned in profile. Andy Jr captions it “My First Picture” and places it next to a self-portrait of himself in September, looking casual with hands in pockets and captioned “A self-timed portrait of the author.” One of his “best shots of Earle” is taken from an angle beneath him so he appears like a diagonal line pointing to the sky.

There are also candids of the two boys at ease in a family room. That same month Andrew Jr. climbed up to their roof and took aerial shots. Some are pasted into the album; others are loose throughout the family archive. In one a camera hangs from his shoulder. Another page is labeled Landscape and divided into Sunset at Pennelwood, Berlin Springs, Michigan, Scene I and Scene II, though the black and white photos make it hard to discern the changing light. This theatricality reappears in other pairings, like his cousin Beverley shown in 1932 and 1939 with a sketch of a grim reaper between them saying “Whew. Time marches on.” His high school yearbook picture, with tie and jacket, is juxtaposed with a smiling self portrait (“P.S. I took it myself.”)

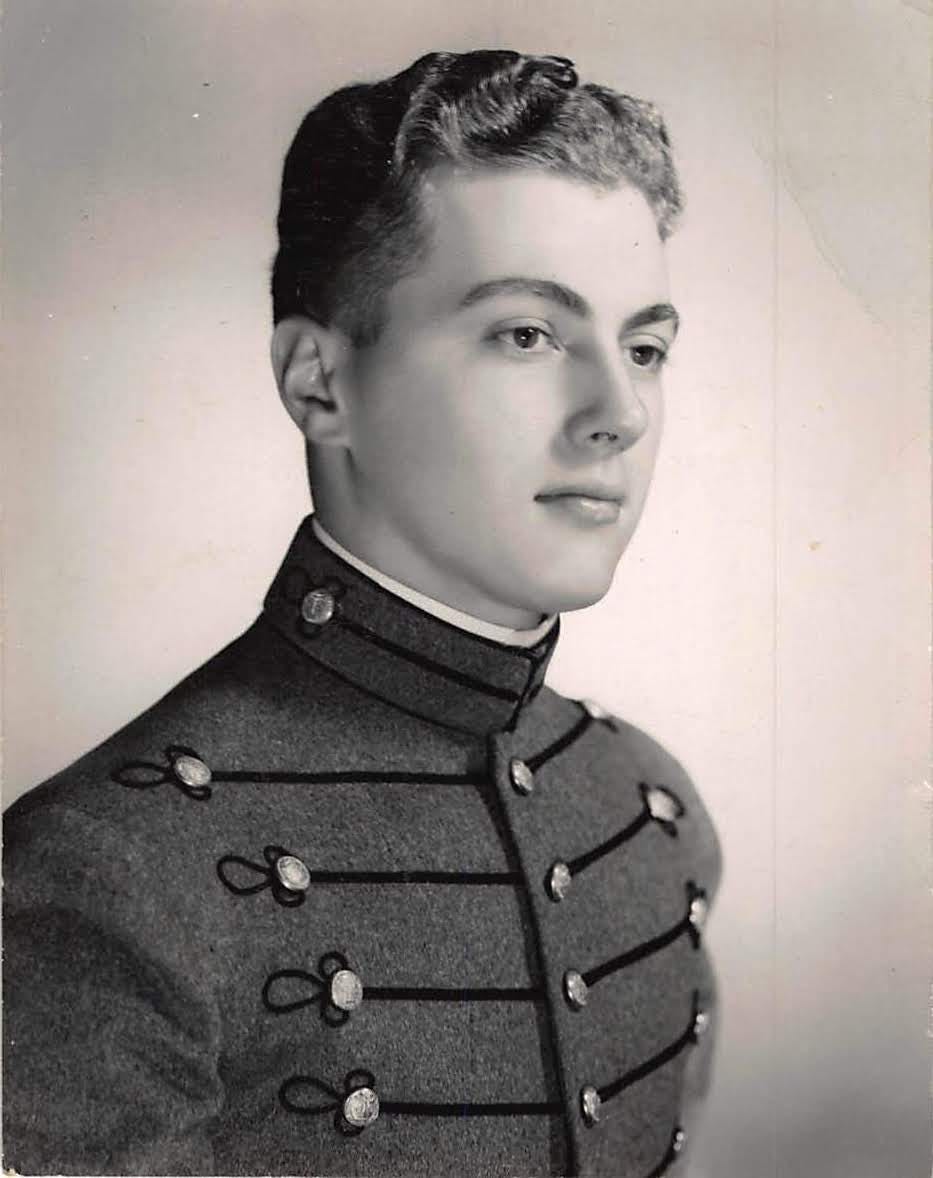

A few months later, Andrew Jr. was recording his life as a new student at the Citadel, where he enrolled as a cadet in the fall of 1941. Throughout, he is both cheery and serious, naming all the buildings he photographs and commenting on his own appearance: “Oops: sort of stiff, eh?” He goes on a furlough into Charleston and documents the streets as well as the ocean beach. He singles out an antique store that his mother would like. Many of these still feel artful, taken at angles and attentive to line and shadow. In August 1942 he’s back home in Chicago, taking pictures of himself and Earle again.

At the Citadel Andrew earned solid Bs and Cs and the occasional A in Civil Engineering or Drawing (his father kept every report card). He reported for active duty in February 1943, completed Basic Training in Miami, and saved the transport receipts for his train trips as well as the letter calling him up. He attended Army Air Force flight school at Foster Field, near Victoria, Texas and sent his parents photos with jaunty messages inscribed on the back like:

“Hi Folks, Here I am in my chute, but it is a different plane, a private one, but better for pictures. I’ll take a lot of pictures before I leave of me and my instructor. Notice the cable on chute and flap. That’s the important part! Tally Ho!”

“Just after my solo flight. Into the showers I went. Striking picture, eh?”

“Yours truly—the H.P. as they call them (Hot Pilot).”

“In my dress outfit. Needs pressing though. When I get my camera I’ll take some better ones.”

It’s not clear who took some of the self portraits. At least one is labeled “Artistic.”

Though Andrew Jr. often photographed Earle, I don’t think my father ever painted his brother. In fact, my father rarely talked about Andy. When asked if Andrew Jr. was interested in art, my father said no, that his brother wanted to be a civil engineer. Engineering seemed far from art to me at the time, but now I think of Andy’s interest in architecture, and his photographic studies, as another piece of the family’s connection to design.

I will tell the tragic story of my uncle’s death in a training flight in 1944 in a guest post on Sunday for the Members’ Corner on

. That death exploded their family, then haunted them. Among the minutia that Andrew saved are a pair of receipts from the late 1970s for wreaths placed on his son’s and wife’s graves at Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago. By then, Andrew Jr had been dead for thirty-plus years and Elsie for ten, but my grandfather was still paying homage, quite literally. Meanwhile, Andrew Jr’s photo album was mouldering in my father’s attic somewhere; we found it after my father’s death in 2011. Now, his photos curl at the edges, coming loose from their sleeves and falling out of order.I’ve written elsewhere about how death drives narratives: E.M. Forster’s famous distinction between “‘The king died and then the queen died’ is a story. ‘The king died, and then the queen died of grief’ is a plot” shows how death can set a plot in motion. Andrew Jr. was only ever dead to me, but his album resurrected him. I’m a biographer by training and this album is the best kind of primary source material: full of personality and personal data. It shows me both his daily life and the arc of his life story, as he moved from high school to air field. It makes visible parts of my father’s life I could never have seen and he never talked about. The captions provide a posthumous echo of his voice. I am very lucky, and grateful, to have it.

Please like, comment, or share to support this newsletter and my writing. I appreciate it! I’d love to hear about your family photo albums in the comments.

My father had a handsome older brother who died at Vimy Ridge, age 19 and probably a virgin, given the family faith. We have a photo and the transcription of a letter. My father never spoke of his brother. These losses cut deep and cast a shadow.

I enjoyed learning about your uncle. I particularly connected with your opening thought "No one occupies more of the Olsen family archive than its missing member: Andrew Jr." I recently came into possession of some of my great-grandmother's documents and artifacts. She outlived her husband and all but one of her children. Among her collection are the papers and clippings related to one of her sons who died as a young man. It's sad to think of those tangible items as the way in which she stayed connected to him. But, as a family history researcher, I'm thankful that they were preserved.