This newsletter has been focused on my recent work on my father’s art career, but I started out as a Victorianist— and wrote a biography of the photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. My title here, From Life, echoes the title of that book, which in turn echoed the captions Cameron inscribed in a bold hand on her prints. Last week I made a lightning trip to London to see this exhibit at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), which pairs her with Francesca Woodman. This week I detour from my usual programming to tell you about it.

At first glance, it’s a curious juxtaposition. Cameron was a middle-aged matron, enmeshed in the literary and artistic society of mid-nineteenth-century England; Woodman made most of her work as an art student at Rhode Island School of Design in the 1970s. What inspired curator Magdalene Keaney to unite these two photographers from different centuries and continents? I admit that I went to the show feeling skeptical.

“I feel that photographs can either document or record reality or they can offer images as an alternative to everyday life: places for the viewer to dream in.” Francesca Woodman, 1980

The title of the show, “Portraits to Dream In,” argues for Cameron and Woodman’s shared theatricality. Both women resisted photography’s association with objective documentation to create images filled with props and costumes, staged scenes and dramatic poses. Both exhibited messy work, marked with handwritten notes, scratches, and tears. It is easy to dismiss Woodman’s self-portraits as adolescent posturing. It is easy to dismiss Cameron’s allegories as maudlin sentimentality. The exhibit’s organization doesn’t help: sections on angels, nature, muses, and doubling, concluding with a room called “Men,” seem like a jumble of themes and forms. Still, I found the NPG exhibit thought-provoking: despite what some reviews seemed to think, the show wasn’t making an argument about influence or equivalence; it was just trying to raise interesting questions, which felt brave.

Where does art come from? Whatever is at hand.

Both women made art from what was closest to them. Woodman used her own body (often nude). Cameron photographed Victorian celebrities she knew personally — like Thomas Carlyle, Charles Darwin, Alfred Tennyson, or Anne Thackeray Ritchie— and her own family, maids, and neighbors. Look at the pairing above: At left, Cameron poses the actress Ellen Terry (then married to her friend G.F. Watts) against a wall, calling it “Sadness.” The image is damaged at the bottom, where the collodion emulsion peeled off. At right, Woodman contorts herself into the photographic frame; her hands and feet are slightly cropped at the edges. Both evoke the Alices of John Tenniel’s famous illustrations for Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland (which was contemporaneous with Cameron’s work from the 1860s)— where a female body is symbolically crushed by a domestic space that can’t contain her.

What does art do? It transforms the subject, the viewer, and the artist herself.

But neither Woodman nor Cameron were interested in simply representing reality, as the show itself and Woodman’s quote above reveal. Cameron’s inscription “From Life” insists that photography starts with the real and transforms it. Cameron turned her maids into madonnas and her family members into characters from Arthurian legends. But her work also transformed herself— from a wife and mother into an artist and professional. Woodman too seems interested in that process of transformation: she seems to be asking, what can I make of myself? An angel, an odalisque, a pillar of stone…. Most of Woodman’s work is small in scale and hard to see clearly, but the exception is her monumental series of caryatids. In these images, young women pose as classical columns and bear some unseen heavy burden, Atlas-like. The images are faceless but lovely, stoic but vulnerable too, with torn and messy edges.

How does art work? Over time.

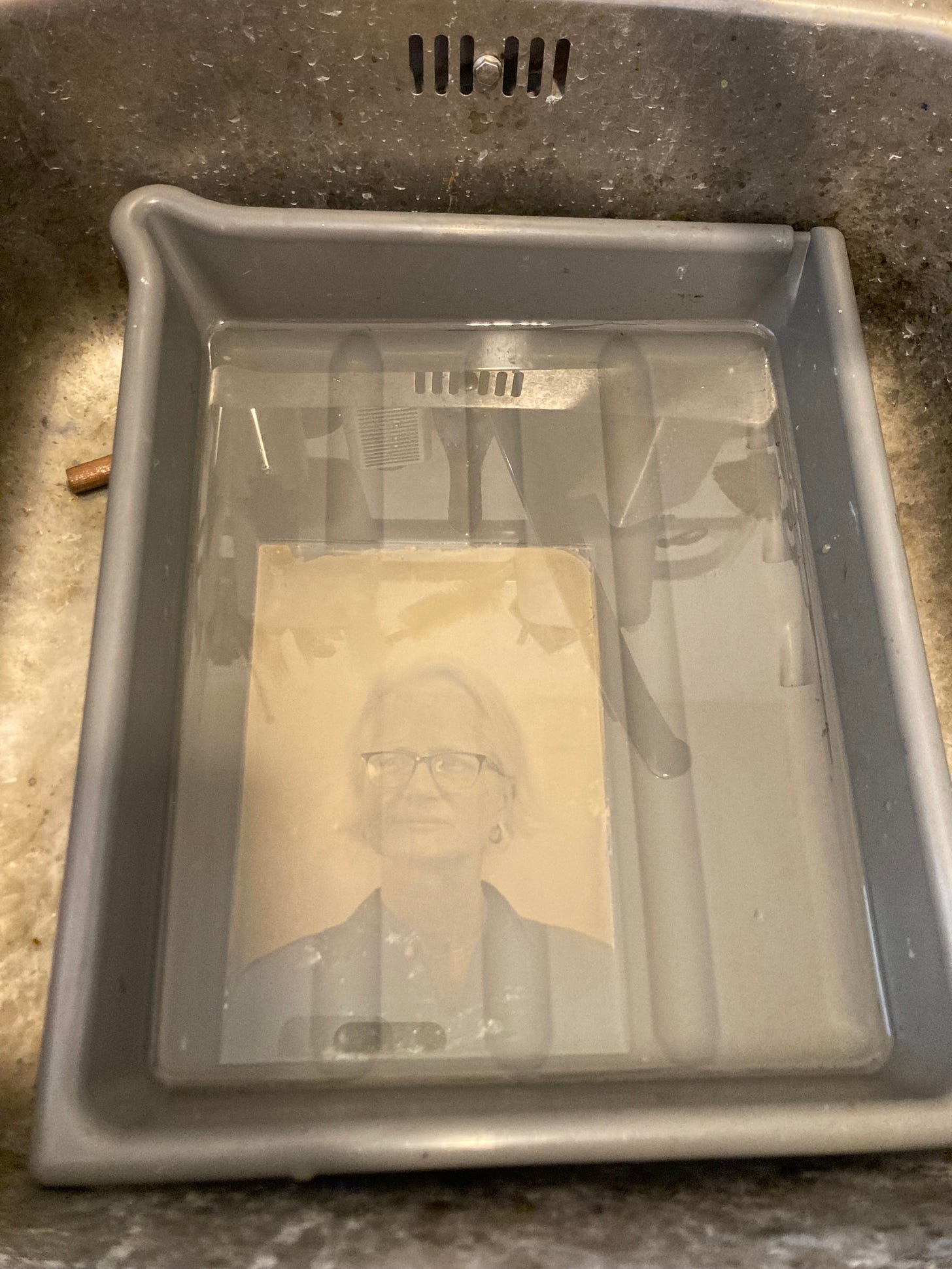

Transformation over time is the fundamental alchemy of photography, in particular. The exposure to light last seconds (for the wet collodion process) when the camera’s aperture opens; the image becomes a negative, then a positive. The wet collodion technique that Cameron used entails preparing a glass negative with special solutions to make it sensitive to light, exposing it in a camera while still wet, and then developing it immediately with more chemical mixtures. The printing— pressing the image against specially-prepared paper—takes place later in direct sunlight. Or at least, those are the basics. After seeing the exhibit I tried it myself for the first time at a workshop with two other women led by photographer Magda Kuca. The four of us took turns holding poses and manipulating the glass plates, wearing gloves and pouring the collodion just so to avoid blackening our hands with silver nitrate. We took frequent breaks from the darkroom to avoid dizziness from the collodion fumes. And then, we watched an image magically emerge, from nothing, transferred invisibly but now visible, a moment caught— not quite permanently, perhaps, but suspended from time. I watched myself becoming.

Suspension. That word explains the photos Woodman made of herself as an angel hovering mid-air, as if caught in the very moment of art-making. I am neither this nor that, she seems to say. It explains Cameron’s moving images, with sitters like Thomas Carlyle blurry with motion or scenes like the sorceress Vivien caught mid-spell, waving her hands. The wet collodion process slows down the immediacy of photography, especially for today’s snapshot culture. We spent hours with Magda to make four glass negatives— one for each of us, and each one unique.

I found this post challenging to write. How to balance the lift of angels’ wings and the weight of those caryatids? How to represent the teetering poise of a single moment in writing? Maybe the questions themselves are enough.

Thanks for reading! I appreciate all feedback — and if you see the show, please let me know what you think! Next week I’ll return to my memoir.

Resources

To learn more about Magda Kuca’s wet collodion workshops and view her own lovely and evocative work, see her website. She’s a wonderful teacher!

At the curator’s talk for the NPG show last week I met a critic writing about the exhibit for Aperture Online and had an interesting conversation about other women photographers in a potential Cameron-Woodman lineage, including Imogen Cunningham, Sally Mann, and Elinor Carucci. When his review posts I’ll add it here.

If you’re near New York City, Woodman is also the subject of a current show at the Gagosian Gallery until April 27th. The highlight of that show is the huge Blueprint for a Temple (II).

If you’re near Milwaukee this spring, watch out for this Cameron show, which has been touring around. I hope to see that too and will share my thoughts. It arrives there from the Jeu de Paume in Paris, where

viewed and wrote about it.

Fascinating! Thank you for alerting me to this exhibition, Victoria. It looks like I'll be able to catch it before it ends on my early summer trip.

…love Woodman’s caryatids. ✨