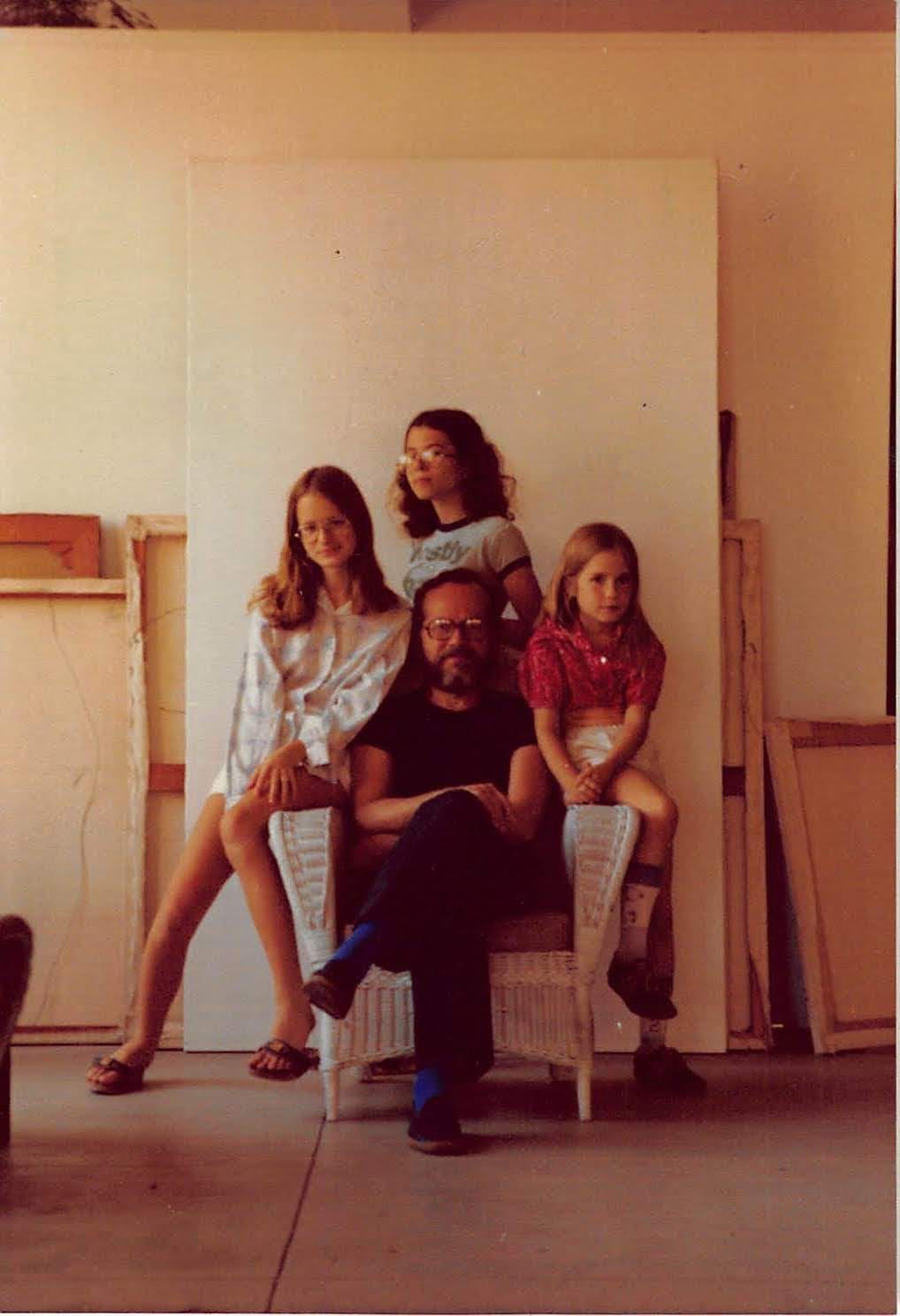

My father sits in a wicker armchair, framed by his three daughters, like a modern King Lear. He moved that armchair, part of a vintage living room set he had spray-painted white, from home to home. The arms had a built-in ledge and that’s where M and I perch, at his left and right hand. T stands behind, in profile between us, so we appear in age order, clockwise. It’s 1976 in my father’s midtown Manhattan loft. Those are his paintings in the background, some stretched canvases, still blank, and others turned around, hiding.

We three girls are grouped carefully around his central figure, like satellites, but each distinct. As in a Renaissance tableau, the outfits differentiate us: my Dr. Scholl’s slides, which I used to wear all the time, with one of my favorite button-down shirts; M’s Snoopy knee socks; T’s Mostly Mozart tee shirt, which identifies her as part of an Upper West Side tribe. Our expressions differentiate us as much as our outfits. I seem to be smirking, a know-it-all. T looks askance. M clasps her hands tightly together; her face reminds me of the central princess in Velazquez’s informal royal portrait Las Meninas. My father Earle is very much the “proud papa,” as he described himself in a letter from around the same time.

Who are we? Or rather, who were we—because my father has been gone for over a decade. In the portrait we seem both open books and closed off, both a single unit and entirely distinct, with each of our faces slightly turned at different angles. Except for Earle, the paterfamilias, who stares out directly at the camera. He looks as neutral as a judge, but I lean into him, as if to signify my firstborn, favored status. Now when I look at this photo I see the tightness of our bond, his centrality, and the ever-presence of art—in the blank canvases behind us, even in my reference to Velazquez. Art was such a common backdrop in our family that I hardly noticed how different it made us.

Earle kept that framed photo on display in all his homes. Going through his sketchbooks to write this, I found a drawing he must have done from it. Labeled “The 3 Graces,” it shows each of his daughters in their distinctive poses, but in the middle is only his own empty hatch-marked chair. He was both central and absent; art put him in the middle and art took him away from us.

I wanted to tell the story of my father Earle Olsen’s art career and its impact on my family, but where should I start? I had never written a memoir, so I’m figured it out as I went along. When you write a memoir you already have expertise in your subject because you know your own life. But you may not be a writer, or have never written a book. You may have been told never to write with the “I” pronoun, which poses a problem for a memoirist. How do you insert yourself into your own life? Where is your voice on the page? What are you trying to say? Why are you writing it in the first place? These are all questions I tackled in writing my own family memoir, called Daddy-O. The Substack you are reading now will share some of my answers, then critique them.

Memoir is a challenging form because it doesn’t have a formula: it doesn’t need a happy ending, like the romance, or a surprise twist, like a mystery. It doesn't need characters, exactly, or plot, though that’s an assumption we'll examine. It lives with one foot in the public realm (you are writing a book, after all) and one in the private (the story is your own). But the slipperiness of the genre can be freeing too, and the memoirist has some built-in advantages, which is perhaps why it is a booming genre.

For example, memoir doesn’t need to be researched or even entirely factual. Memoir relies on memory, which is notoriously subjective. Your memoir will focus on your memories, which may not be reliable or objective. That’s fine. You can also bring your whole self, and all your other skills, to bear on this project. Maybe you’re a genealogist who knows research or a receptionist who’s good with people. In my case, I’ve published a biography of a photographer and I taught expository writing to college students–mostly actors, dancers, and filmmakers–for eleven years. I was never an artist myself, nor even a creative writer. I’ve studied autobiographies as a graduate student of literature; I’ve read a lot of personal essays.

We covered essay structure in my college-writing classes and I taught my students to begin with something concrete. Open with a piece of evidence that you can read or interpret for your readers. Describing an object or a place can anchor your story, set up your themes, and introduce your voice. That’s why I began with the photograph above, an object evoking my family’s past. Writing guides advise you to “show, don’t tell” and visual description achieves this: the portrait above reveals some of our specificity and complexity at a glance. It gives my family a coherence we didn’t necessarily have in daily life—and that would be impossible to paraphrase.

The opening of your book should set a stage; in my case, the photograph evokes the theatrical stage of King Lear. Evoking that play in the first sentence sets up some expectations, consciously or unconsciously: my father will be a powerful but flawed character, maybe even tragic. There will be a loyal daughter, and a daughter who betrays him (might she be the same person?). The opening stage should include props and settings that you’ll need later as you tell your story: here, a home but a specific home, an artist’s loft. Include a cast of characters who will return later; my central character is literally posing in a chair, face forward. The others are both generic types (oldest, middle, and youngest daughter) and themselves. Use the opening to introduce a through-line: here, the theme of art and family. It’s all there, already, on the first page. And establish a tone of authority: I know what I’m talking about. I was there. I am not the central character of my family memoir, nor am I the photographer of this image, but I am in the picture from the start. Where are you in your story? Position yourself.

But most importantly, tell a story that leaves something out, that raises questions the rest of the narrative will answer. That’s what keeps readers engaged and turning pages. Everyone knows that. So where is the story in my opening? What question do I ask, directly? Who are we? You don’t know, but do you care? We aren’t famous people and nothing interesting or surprising has happened to us yet. All I have to entice you with so far are my writing skills. What question do I ask, indirectly? How did art take my father away from us? That is the main question I raise in that opening. Any question that gets raised in a memoir should have an automatic corollary: And why does that matter?

Let me backup to show you how I got here: in my first draft this photograph appeared later in the manuscript but my very first reader understood it belonged at the beginning. It was an entry point. There is always more than one way to enter a story, and the one you choose will tell your reader where you intend to go next. Which door will you open? That depends on which room you want to enter. Here the room I enter is filled with art and literature references– Shakespeare, Velazquez, Mozart– but also pop culture like Snoopy and Dr. Scholls. My world is a little contradictory, maybe.

This is where I’m going with that last sentence: “He was both central and absent; art put him in the middle and art took him away from us.” Central and absent are not actually opposites, but askew. The semicolon joins two similar points, made in two different ways. It moves my father from subject “he” to object “him,” which effectively kills him. The first half of the sentence is simple: the adjectives central and absent both two syllables and equally emphasized. The second half shifts the rhythm toward monosyllabic thumps, like a drum, with short repeated words like “art” and “him.” The parallel structure of “art put him in the middle and art took him away from us” makes opposites of “put” and “took,” which again aren’t quite a matched pair. The sentence as a whole–the paragraph, even–leads the reader from my father/he to us.

Who is that us? Introduce your characters. I describe myself and my sisters and what can you tell already? “Know it all” tells you that I am uncomfortable with my expertise, with telling all this. I use the word “paterfamilias:” I am a snob. But “smirk” undermines the authority I have as the “firstborn” in the first person. Like me, T is described with some ambivalence (“askance” even sounds like ambivalence), whereas M is unreservedly idealized, a princess, if a little hidden. How will this unfold? You know my father is dead. What happened to him? Why is he so important to me? If there is an element in this intro that isn’t well enough developed it is probably the element of suspense: there is little drama here yet, and no motion. Narrative momentum in fiction or drama comes from scenes, where characters interact with each other or their environments. My opening is not a scene at all. It’s a still photograph, so it’s static.

Did I think of all that as I drafted? No. In fact, I usually advised my students to write their introductions last, when they knew the most about where their piece was heading. I write well but that’s not the point here. The point of this essay is to show you how I got here, transparently. That means including the mistakes within the successes, because they are intertwined. I made many choices in that opening piece of writing: I dropped in a few orienting facts like a date, a place, some names, but I focused on the evidence in front of me, the photograph itself. Soon, I will tell you more about those people and that art; I will explore the idea of art and family.

But here’s the other thing.

I’m proud of that opening, the analysis of the family portrait. I worked hard on it. I sent it as a writing sample to literary agents and editors at publishing houses that accept un-agented submissions in hopes of finding a publisher for the completed manuscript. I turned it into a standalone essay and pitched it to online journals and literary reviews. And no one took it. Which is not to say that a/ it’s not good after all, or b/traditional publishing is broken. I didn’t exhaust my options. I could have kept sending it out and might have found the right fit for it eventually. Instead, I chose this path: sharing excerpts from the book while showing you how I shaped it on the page– and where I went wrong. They can be read in any order. I critique my own efforts so you can learn from my false starts.

Eventually I intend to keep the memoir itself free here, but put some of the other material behind a pay wall. For now, everything is free and I encourage you to try the exercises that follow the critiques and see if these posts can help you structure your memoir, clarify your meaning, or just generally tune your writing skills.

Exercise: Choose a photograph related to your memoir project and describe it carefully in about a paragraph. It could be a self portrait at a pivotal age, an image of an important place or location, or any other visual artifact relating to your project. Make sure to spend some time on close description, but notice how your description can contribute to an interpretation, a reading of the image. Then draft another paragraph interpreting that image. What does it mean to you? Make sure to link the interpretation to specific parts of the description. Consider too, how does this image fit into the whole of your project? The completed exercise should be only 2-3 paragraphs long.

Some memoirs that are structured through visual analysis include Janet Malcolm’s Still Pictures and Sally Mann’s Hold Still. Share your exercise below in the comments— if you want feedback please say so and I will respond to it. I appreciate any likes, shares, or comments!

Somehow I've only just started reading your marvelous blog. thank you, I'm enjoying it so much.

Your analysis of the portrait is so nuanced and enticing!

Also: what a gift from your father! --the drawing that has “his own empty hatch-marked chair.” That’s a crazy good prompt for your thinking.