My Mother, on Paper

(In which I destroy evidence)

When my father died I was the only daughter living within one hundred miles of his house upstate. I was executor of his estate. I had traveled back and forth by train and car when he had surgery for kidney cancer, then during his final months in a VA hospital in Albany. My sisters flew in and out from either direction—Portland, Oregon and the south of France.

I had written her out there so I will write her in here.

At the end of that tough summer of 2011, when he died, we all spent much of August emptying his house. My mother helped, packing boxes and watching our kids while we sorted through stuff we wanted or not. Then, when we arranged a memorial in his town, she suddenly refused to attend. “He erased me from his house,” she complained. “There was no evidence of my part in his life.” I was baffled. True, there were no photos or objects from their life together, but a huge canvas of her face hung on his dining room wall. And what did she expect? They had been divorced for forty years by then. But she had her own version of this story (which she told me after reading mine): she was hurt that I had forgotten to mention her in my father’s obituary. And, astonishingly, I had indeed omitted her. To me, she hadn’t been an important part of my father’s life. My parents had been so utterly separated in my own experience of them that I had forgotten her role– even though it produced me. I had written her out there so I will write her in here.

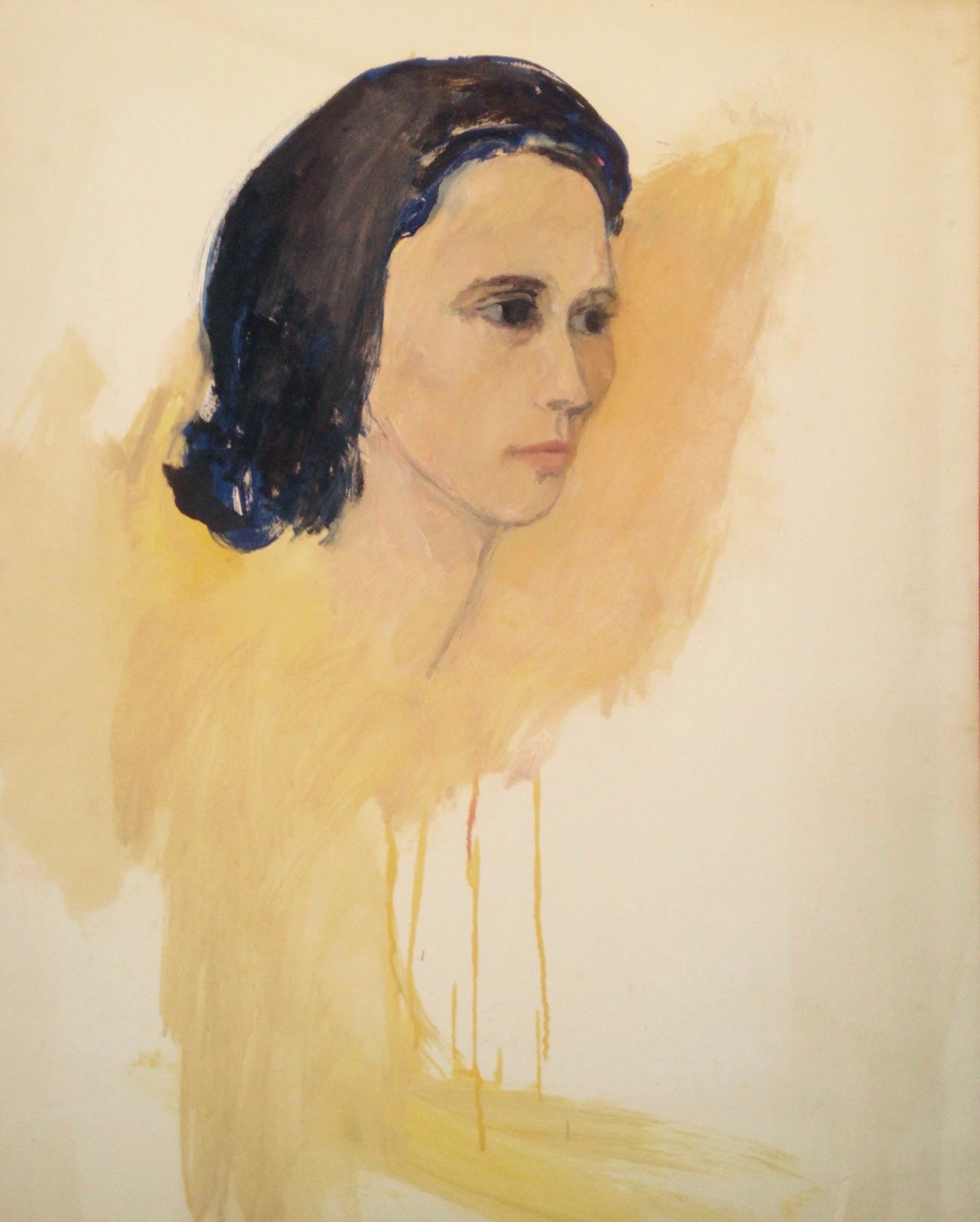

But my mother is hard to represent, though my father painted her a few times. He made two huge paintings of female heads that we assumed were my mother, though she says she doesn’t remember sitting for them. They are monumental. In another painting that is more recognizable her composed face stares out, slightly guarded, from a roughed out figure. (My mother still keeps this portrait on her bedroom wall.) In another unfinished sketch she is in profile, with very dark hair styled à la 1950s with an upward curl that she never had in real life. Yellow paint drips from her neck.

Unlike my father, my mother is still very much around— while I wrote this memoir, during the pandemic, she was often in the other room, conducting phone sessions with her psychotherapy patients. I saw her last week for dinner at her apartment, and over the weekend for lunch; she’s coming over tomorrow for Thanksgiving. She subscribes to this Substack (hi mom!), though I doubt she reads it. She is 90 years old and has short-term memory problems, though she’s just as sharp as ever about everything in the moment.

Last week I sorted through four banker’s boxes full of her papers, which we had stored when we emptied her office for renting. As the monthly charges for storage grew and grew my sister and I decided it was time to sort and purge it all. We had a few items delivered back to my house (the rest was donated to a charity). But I knew that, in my mother’s case, “papers” might mean confidential notes from her private practice in psychotherapy — or the family histories she took from parents and children as a social worker in New York City’s public schools. I was right. Looking through those documents, I found names and address of her patients, insurance claim documents, and detailed handwritten notes from sessions. Confusingly, many of the session notes were written in the first person so at first I thought some were her own journals. “Felt good at dinner,” she wrote (I paraphrase). “It was the right thing for me to do. Stay in the moment. Then run off some place to discuss.” She carefully used initials in her notes, though it would be easy for me to reconstruct identities if I wanted to.

Of course I want to! My mother spent sixty years of her life seeing patients— these records went back to before I was born. They document the private hours my mother spent away from me and my sisters, the secret part of her life that I never knew about (we used to tiptoe past her closed door when she held sessions in the apartment we grew up in. “Be quiet!,” she’d say).

And they are therapy sessions! I imagine them filled with family dramas and personal revelations. I would see how my mother navigated emotional terrains and confirm her impact on the people she met with. Among the stacks of official papers were also drawings from children she evaluated for what was then called the Committee on the Handicapped (“I love you, Mrs. Olsen!” scrawled in a fat marker with a big red heart, before she changed from my father’s last name) and Hallmark holiday cards from adults she saw for decades. It was very moving.

So last week I took 16 pounds of my mother’s professional life to a shredder….

But of course it all had to go. They were identifiable and protected by privacy laws. So last week I took 16 pounds of my mother’s professional life to a shredder. It went against every impulse I have as a biographer (what I would have done to have that much documentation of my father’s career! On the other hand, how would I have felt to have a psychologists’s adult daughter reading the records of my therapy sessions??) I brought several of the handwritten notebooks uptown to my mother’s apartment, in case she wanted to browse through them before we shredded those too (“these should bring back some memories,” she told me, flipping through them).

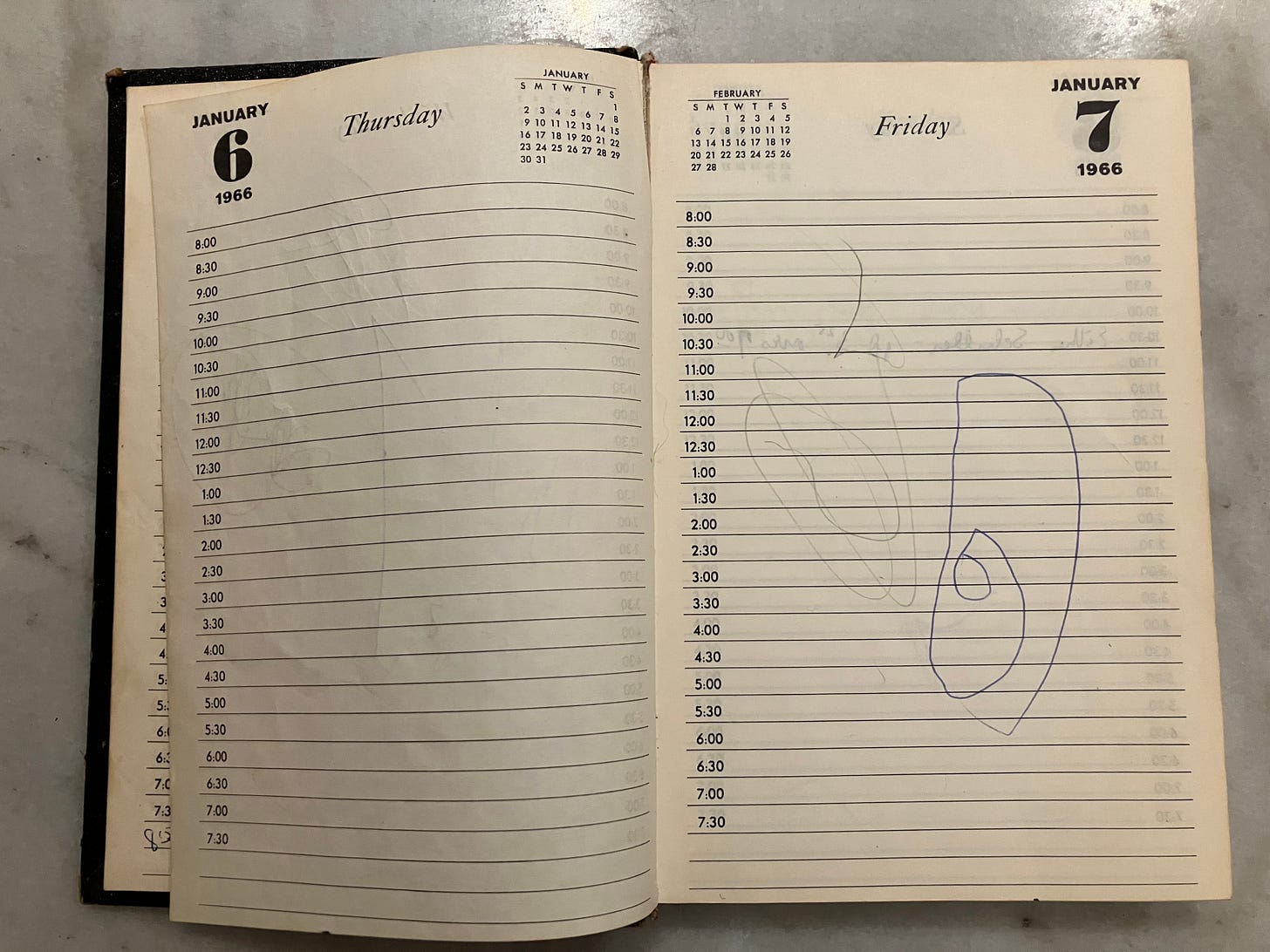

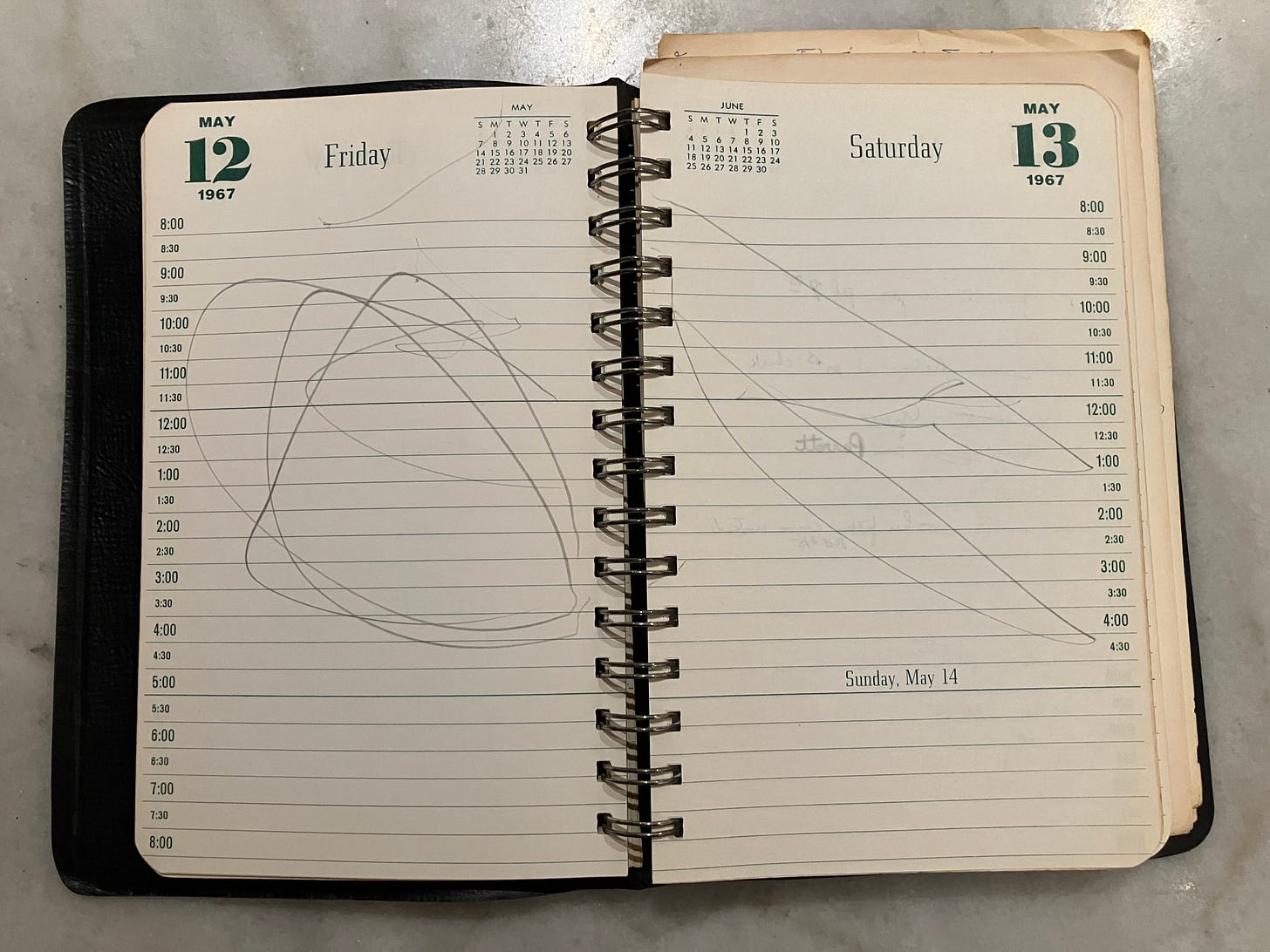

For myself, I saved my mother’s calendar agendas, which refer to her sessions but only with initials. They were too precious as documentation of her daily life (and I wanted to search them for signs of my own presence). Flipping through the standardized pages, I found a few defaced with scribbles. Could those have been my own toddler marks? My sister’s? It made me dizzy. I asked my mother if she thought one of us had invaded her datebooks and she laughed. “Probably!”

This essay is full of parentheses, I realize, as I try to tell two parallel stories— a professional and personal one, a mother’s and a daughter’s, a writer’s and a researcher’s. I’m also trying to show my process itself— the sorting and thinking and feeling that goes on behind the words. It’s a clumsy process, occurring here in real time and place— this week in my house and my mother’s apartment, by hand. Now, it is most fully integrated in my memory, where I still know the names and bits of stories of those patients whose records I’ve destroyed. Even that abstraction feels dangerous— but it’s an act of transference too: my mother’s memories becoming mine, my writing representing her. The two of us, merging back together, in the moment.

Have you ever had to destroy evidence, so to speak? I look forward to any thoughts or comments. And I always appreciate any shares or reposts that help me reach new readers. In this week of thanks-giving, thanks, as always, for reading. I’m very grateful for you all!

How could you not be curious about the stories told in those files? How could you not destroy them? Your mother’s compassion and searching intelligence shine in the portraits.

In the summer of 1950, my mother spent the summer in her grandfather's village in Ireland, where she met a girl her own age. They were friends the rest of their lives. The two girls, later two women, had a correspondence that lasted almost 70 years. When my mother died, we cleared out her house. I went looking for the letters-- I wanted to return them to her friend, who was now almost 90 and suffering from memory loss and might have treasured them. But my mother had destroyed the letters. I couldn't believe it--70 years of their lives committed to paper and now gone! I had no intention of reading them, but she couldn't know that. She also destroyed a handful of letters my father wrote to her before they were married, along with a lot of personal memorabilia from when she was a young person, including a photo album when she was in a Saint Patrick's Day beauty contest and rode in the Saint Patrick's parade float. She no doubt thought that it was all meaningless to anyone else, and, in the case of the letters, nobody's business. Such a loss.

I am sorry there is no way of preserving personal stories like these, or those of your mother's clients, for future generations, in a way that would ensure that everyone's privacy was respected, and the stories in them were used for the right purpose.