Hello and welcome to May! This month I’ll be sharing several pieces about the life and death of my father’s older brother, Andrew Jr. Here, you’ll first meet him through a piece I pulled from my archive. Enjoy!

At The Hare with the Amber Eyes show at the Jewish Museum, tables filled with small Japanese figurines were laid out in each room — warriors, animals, mythical creatures, all carved in porcelain. Called netsuke, the objects were an integral part of the book that inspired the exhibit, Edmund de Waal’s 2010 book of the same name, in which he traces his family history from 19th-century Odessa, through Europe, to 20th-century Japan. In 2022 the original objects that his ancestors carried from country to country were put on display in New York City.

In the book, the netsuke collection provides the thread, like a physical connection, between the people and places de Waal writes about. A ceramicist himself, de Waal uses the objects as literal representations of the family lineage as they are handed from person to person: bought in Paris by Charles Ephrussi in the 1870s, given as a wedding present to a nephew in Austria, hidden by a servant when the Nazis invaded in 1938, brought by a great-nephew to Japan after World War II, and finally inherited by a great-great-nephew, de Waal himself. The objects circle the family and bring coherence to their story.

They remain objects though, and de Waal writes a lot about the feel of them. They are small enough to keep in a pocket or close in a hand, like a talisman. As children, his grandmother and her siblings played with them on the floor of their mother’s dressing room in Vienna. It was a special treat that bonded them all together.

The Ephrussis were a very wealthy Jewish banking family and the netsuke collection is very valuable. Most of the objects the extended family owned in the 1930s were seized by the Nazis and dispersed. The unexpected survival of the netsukes provides most of the suspense for the book. My family has nothing like that in our history, but I did inherit boxes and boxes of things that my grandfather, a commercial designer, and my father, an artist, left behind after their deaths. My sisters and I divided them up, but most are in my basement still, ill preserved.

When I saw the exhibit I was planning a research trip to Chicago, where my father’s family lived for three generations, during the same years that the Ephrussis were criss-crossing Europe and Japan with their netsuke. I had read de Waal’s book, but I was really there to see the objects, to be in their presence. I loved that they had eventually circled back to their origins in Japan, though they were now dispersed again. Some talismanic objects, I thought, seem to pull like magnets back to their homes. I wondered, was there something in my basement that I could bring back to Chicago?

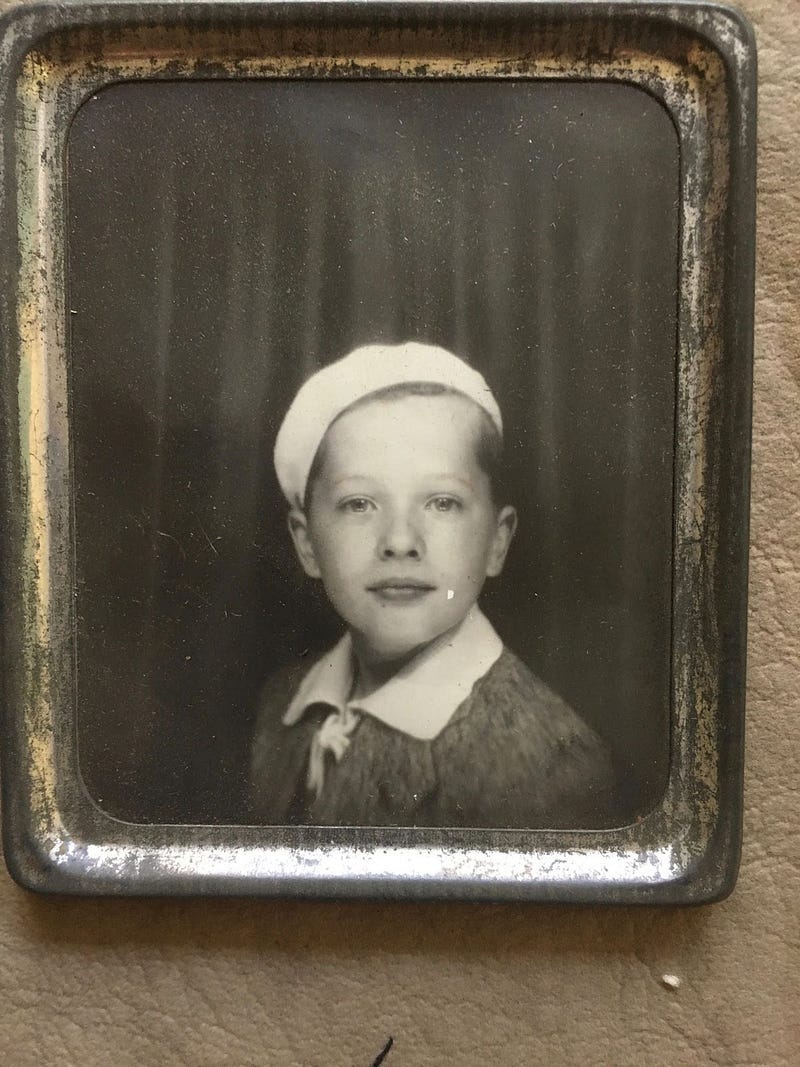

Like these photomatic portraits, taken in 1937, perhaps? The two images are the “thingiest” of the many photographs in the albums and boxes my sisters and I inherited. Like the netsuke, they are pocket-sized, about three by two inches, but made of a soft metal like tin. Produced in photomatic booths popular around the United States in the 1930s, they document my father and his older brother on one particular day (May 25, 1937) in one particular place (Union Station, Chicago) in three dimensions.

My father, Earle, is boyish in his sailor cap, his face open and eager. He was ten years old but seems younger. His older brother, Andrew Jr., seems happy too, and much more mature at fourteen. May 25th was their father’s birthday so perhaps the family had traveled downtown from their home on the South Side, and celebrated with a meal at Fred Harvey’s Union Station restaurant, then documented the day with a photo. These portraits seem to commemorate a family unity that I know didn’t last long. The people are all gone now.

That itself is very poignant—that these photos exist at all when the people and places have disappeared. Union Station is still there, but those old-fashioned photo booths are mostly gone, though I remember them from my childhood and some still exist as nostalgia items. A quick Google search shows they can be rented for special occasions. I was used to seeing the paper strips of five shots that would emerge, mysteriously, from the inside of the box-like room, but I had never before seen any like these, single squares printed on metal. They fascinated me in a way that’s hard to convey in two dimensions here. I held them in my hands, running a thumb along the sharp metal edges. I’d take them back to Chicago, I thought, and bring them to Union Station. I’d walk around with them in my pocket….

The notion made no sense. I could lose them, and they were irreplaceable. I left them at home.

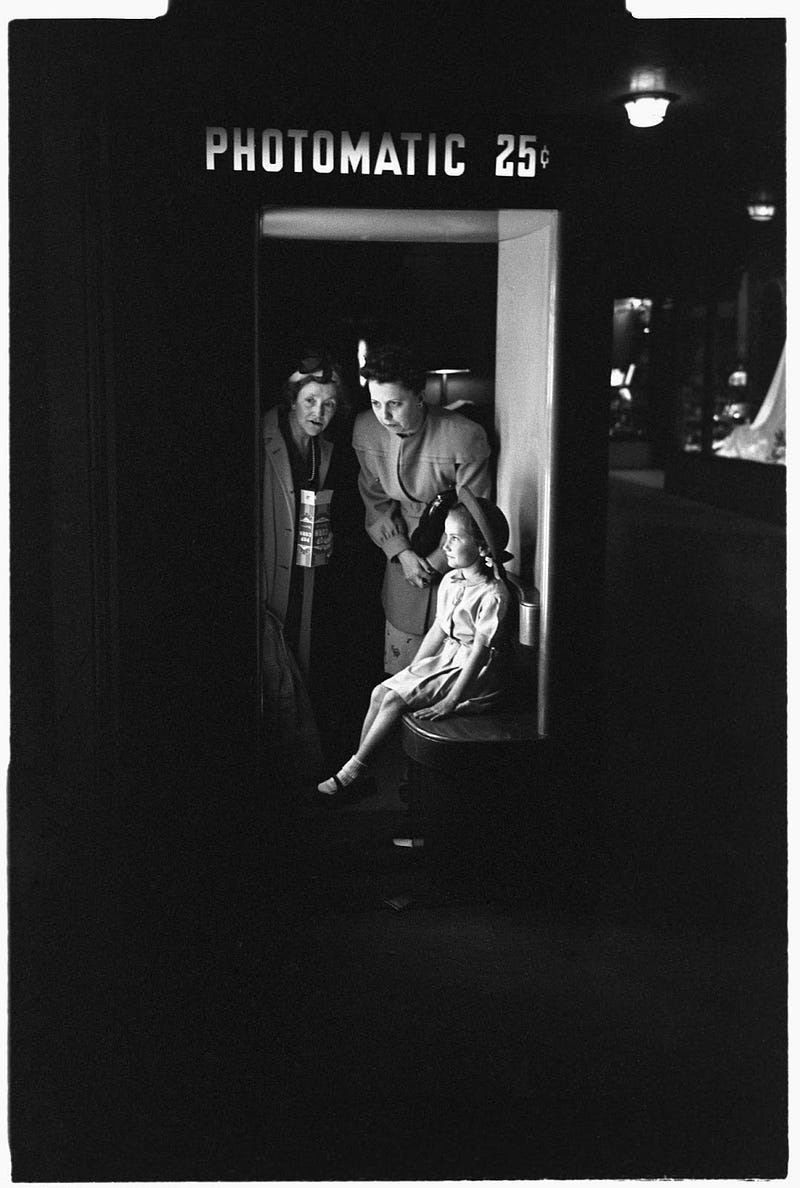

Researching those photomatic booths I came across this wonderful image by Esther Bubley, a photojournalist of the 1940s. The dramatic lighting on the child makes the scene feel theatrical and mysterious. An ordinary family outing suddenly glows with the sacred. But unlike the tin objects I held in my hand, or the netsukes in de Waal’s family, this paper/pixel version flattens the reality. It’s no one’s memory any more. There’s nothing to hold onto.

What do you remember about those old-fashioned photo booths? Please like, share, comment! And stay tuned for more about Andrew Jr. later this month.

Writing exercise: Find and describe a three-dimensional object that matters to your family story. Hold it in your hand, if you can. Write about both its concrete form and its abstract significance in your family life. Another example of an object story from my own archive is my post about my grandmother Elsie, whose portrait was made into a wearable button. If the object serves as a relic, what does it signify?

REMINDER: I’ve opened a Calendly link for office hours so readers can schedule 15 minute introductory calls with me on Google Meet. Bring your writing questions or just say hi!

I loved The Hare with Amber Eyes - but I agree, better to leave the objects at home! Wonderful portraits of your dad and his brother, I especially love the way your father looks at the camera so confidently. My grandmother passed away last month, and I found similar photos-on-tin of her and my grandfather in their things. They are treasures. But they also remind me that I should be printing out some of the photos from my phone! All of these pictures that we're all taking these days are likely to just disappear into nothingness.

Thanks, as always, for sharing your father, Victoria. The love really comes through in the portrait that you're painting...