A family memoir in art and artifacts

The making of meaning starts with evidence, the data points that stretch like beads along a thread of thinking. In this metaphor pieces of evidence are like shells on the beach: three-dimensional objects of various shapes and sizes and origins that one might look for actively or come across by accident. But evidence can also be abstract, like a memory or a sensation, an experience that becomes a poem for an artist or an insight for a psychologist, a bodily symptom that leads to a medical diagnosis. It can be a story, a song, a smell, or a taste, like Proust’s madeleine. It’s easy to believe that when evidence is strung together into an interpretation — a theory of relativity or a version of history, for example — that the thinking, the thread, is the subjective part. After all, another thinker could take the same pieces of evidence and assemble a different necklace altogether, though the beads are the same. Evidence does not work like a jigsaw puzzle then, where the pieces only fit together in one way and produce one true picture, one solution to “whodunit.” The thinker who does the work of inferring, organizing, and assembling the pieces is doing creative work, even if it’s in a legal or scientific domain.

But pieces of evidence are not exactly like beads or shells either — or if they are, they don’t hold their shape. The decisive apples that Eve bit into and fell on Isaac Newton’s head are not around to re-examine. The bones of one epoch become fossils in another. A fertility figure once handled in a ceremony can become a statue behind a glass vitrine in a distant museum. Time, location, and context don’t just affect the interpretation of physical evidence (we know that), they affect the objects themselves (we can see that with our own eyes). Which makes it difficult to distinguish evidence from interpretation, the dancer from the dance from the audience.

This is a roundabout way of introducing a new research project, which attempts to make sense of evidence in front of me, whether I sought it out or it was thrust upon me, whether it was found in a library or a battered briefcase monogrammed APO. This pre-story provides a brief rationale for my method, which is both academic and personal. In short, this potential family memoir will be my attempt to make a coherent story out of certain artifacts relating to art and advertising that I inherited (from my father and his father) or stumbled across (in my research into nineteenth- and twentieth-century visual culture). It centers on those two men — Earle Olsen, artist, and Andrew P. Olsen, graphic designer — to investigate their particular relationship and more general cultural assumptions about art. It spans Europe and Chicago, as well as New York City in between. It enters department stores in 1920 and visits art galleries the 1960s, but begins with me in a basement in present-day Brooklyn.

Biographers are used to the historical record’s gaps; working in archives, we are used to pages that crumble as you turn them, as well as signs of mold and decay. But historical evidence is not only in libraries and not only on paper. The end of the nineteenth century saw the burgeoning of a collector’s culture. Wealthy art patrons like Isabella Stewart Gardner or Henry Frick began to amass the collections that bear their names today in the mansions transformed into museums. Successful industrialists like Henry Ford bought up furniture, farm equipment, even outmoded machinery, creating a three-dimensional archive of Americana. Mass production allowed even average Americans to collect ephemera like baseball cards, postage stamps, or vintage toys. For most of us this vast heap of stuff may seem random, but historians can see a pattern in it. They can read all the beads and shells, the photographs and scrapbooks as well as the collectibles, for the signs of an individual’s values, a culture’s obsessions, a society’s priorities. They can read what’s there and what’s not there. My father’s house overflowed with stuff he picked up at yard sales and antique stores, in trips to Europe in the 1950s and on Saturday nights at the country auctions in upstate New York through the 2000s. He left very few letters, the biographer’s usual gold. His ashes were dispersed years ago but his material self is still, weirdly, buried in my basement.

My basement is both a physical place and a metaphor, of course. It is the basement too, an imaginary place for repressed memories and emotions one would rather avoid or deny. There is evidence there that I still haven’t confronted — like the lists Andrew Sr. kept of the money he gifted his son through the 1970s, supporting my father after my parents’ divorce. During that decade my father turned fifty, bought a summer house on Long Island, and regularly reneged on his childcare payments. Inevitably, the basement leads to other basements, creating a trail of connections forged from a single mention in a newspaper article or a first name dropped into a letter. My father’s letters have led me to “Fred” and “Flora,” who presumably have basements of their own. A conventional studio portrait of my father in 1952 is a slim connection to the artist Walter Pach; another photo links him to Hans Namuth, who famously filmed Jackson Pollock painting in Springs.

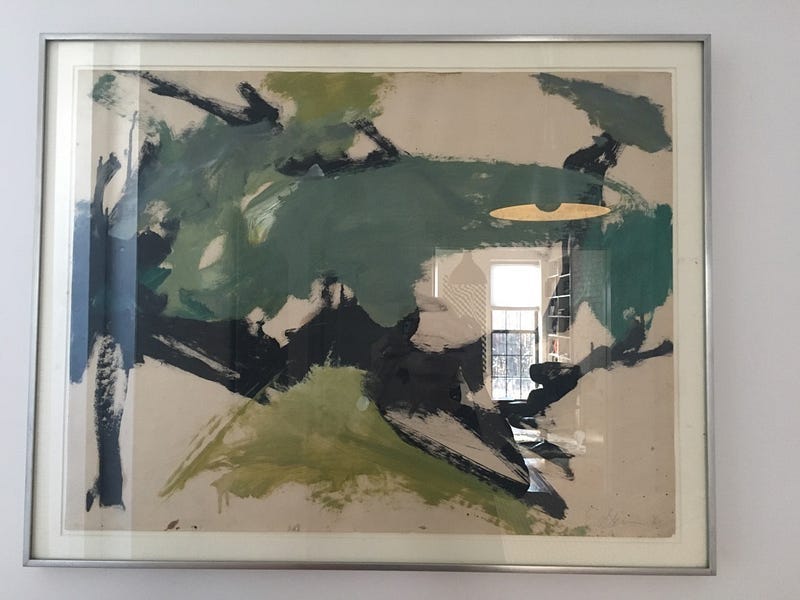

My father lived on the peripheries of abstract expressionism, which is back in the news with a major exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City: he was there in the rooms, in New York City, but never central to the movement. Wandering through that show yesterday, I felt the echoes of all the times I went to the Met with my dad (did I actually see that Clyfford Still retrospective with him there in 1979? I would have been fifteen and it’s possible.) My father’s abstract canvas from 1960 (shown below as it hangs in my bedroom, reflecting the window near my desk and crooked like all my snapshots) resembles the Franz Kline in the Met’s exhibit (“Black, White, and Gray,” 1959), but the implication that his work was derivative would have stung my father. He exhibited in the 1950s, then stopped painting in the 1960s when my sisters and I were born, then started again after divorcing my mother in 1972. He continued painting until his death in 2011, leaving behind hundreds of early canvases and thousands of foam core boards that he produced nearly every day after his early retirement. (“Early” a pun on Earle!)

So here’s what to expect from this project: there will be too many Andrews and Andys and ands. It will take pieces of evidence, seemingly fixed in place, and move them around into new configurations, adding photographs, sketchbooks, school records and army discharge papers, signet rings and costume jewelry. It will chase down dead ends and long-dead relatives. And it will try to make a personal story into something historical. Stay tuned. You’ll find more bits of writing here and on my website.

Originally published at www.victoriaolsen.com on March 14, 2019.