The Family Plot

Reckoning with death on an anniversary

In August 1980 I was surprised to find my father in the kitchen of my mother’s apartment, sitting in the corner and talking on the phone mounted to that wall. My parents had divorced years earlier—and interacted as little as possible. “My father died,” he announced, looking shaken, and the memory blurs with all the other important scenes from that kitchen, like my father, incongruously, comforting my mother when her father died in 1971. The loss of my maternal grandfather, when I was seven years old, had led to an early epiphany: “so when people die,” I worked out slowly with my mother. “They can’t tell us where they went. That’s why we don’t know what happens after death.” That felt huge. My mother gave me an odd look as she nodded. Had I been stupid or clever? I wasn’t sure.

When my father’s father Andrew died my sisters and I attended neither the funeral in Florida nor the interment at Oak Woods Cemetery on the South Side of Chicago. We were teenagers, and didn’t question that we weren’t invited. All of my father’s family lies in Oak Woods, where my grandfather had pre-purchased a plot when his own parents died. I still have that deed among the papers he left behind. Andrew even kept correspondence from his lawyer in the 1930s confirming that his wife Elsie would be entitled to be buried there; when she died in 1968 she was; when he died in 1980 he was too. In addition to the correspondence with the cemetery itself he saved a small piece of paper with a handwritten name and address, labeled “OAK WOODS CEMETERY GUARD.” Why he wanted that was anyone’s guess.

Founded in 1853, Oak Woods Cemetery is now best known as the resting place for famous Black Chicagoans like Ida B. Wells, Harold Washington, and Jesse Owens. My father grew up on the South Side but the Chicago of Richard Wright’s Native Son (1940) was foreign to him. He was uncomfortable talking about race, and never had any friends who weren’t white. In the 1950s, while Baldwin was excoriating American racism, my grandparents were part of the white flight that left the desegregating South Side for a northern suburb. My father never examined his own internalized racism: even when he visited my sister at the University of Chicago in the mid-1980s he never ventured back into his old neighborhood, about fifteen blocks further south. “It’s dangerous now,” he’d say.

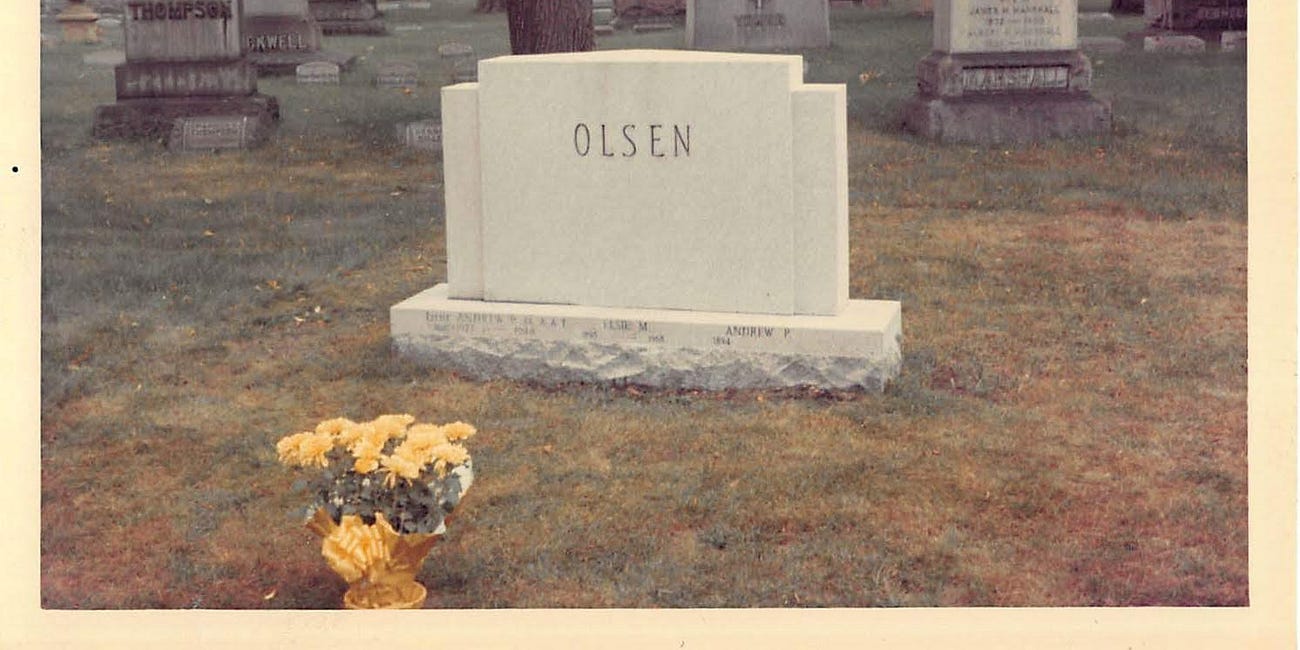

I first tried to visit Oak Woods in October 2019, during a research trip to Chicago. My husband and I had spent an afternoon in Andersonville, talking to artists my father had known in school, then driven an hour across the city to the South Side. By the time we got there the gates were locked. In February 2022 I tried again. I went by myself, taking a train to a bus, then walking through the bitter cold. I had been forced to buy some winter boots because I was ill prepared for the snow. The tombstone was a simple rectangle, much like the Kleenex boxes my grandfather had designed. The Olsen family names lined up on the long horizontal that faced front: Andrew Jr, Elsie, and Andrew — in order of their deaths, the youngest of them dying first. I had to brush away ice from the shorter side of the rectangle to read the name of the baby girl they lost between Andrew Jr’s birth and Earle’s: MARGUERITE JANE (1925). There were two blank sides that may have been reserved for Earle, but he had opted for cremation. I had arrived empty-handed, with nothing to leave there as a token of remembrance.

After Earle’s death in 2011 my sisters and I found a series of black-and-white studies he had made of his father on his deathbed. They must have been imagined because my father wasn’t present for my grandfather’s death in Florida. They all show heads in profile, some on a bed. They are sketchy and feel unfinished, though the life was over. In one a dark cloud or miasma seems to be leaving the prone figure, who stares up at the sky. They are a reckoning of some sort between son and father, with the paternal body, like Baldwin’s with his father’s in “Notes of a Native Son.” Like Baldwin, my father may have been using his father’s death to see an old antagonism from a new angle.

When my father was dying—the 13th anniversary of his death was yesterday—he looked much the same, with a drawn face and eyes uplifted. I took photographs of him like that, but won’t display them here, out of what we vaguely call “respect for the dead.” (Death is private and embarrassing.) Towards the end I asked my father what he was looking at and he answered, Emily-Dickinson-like, “eternity.”

This excerpt from my memoir about my fathers’s art career is also an experiment in representing grief. It builds on my previous post about James Baldwin’s representation of his father’s death. I intend it to be a study in black and white, like my father’s imagined death portraits. I want to leave it a little rough and unfinished too, like those. For another post about family plots, see here:

Please like, share, or comment below! I am interested in your thoughts, impressions, experiences…. Please note that I will be shifting to posting less often in August— to mark it as vacation and also focus on other writing. But I will be back! Thank you for reading!

I enjoyed the crosscurrents in this piece between black and white, and the way the specific images and ideas you include reference that...white snow, black/white racial divide, the black and white studies, your photos of your father (b&w?), and tying it all together, the 'roughness --visual, emotional, contextual.

Your exploration of your father's life continues to fascinate me.

I hope you have a lovely break in August.