This post is a swerve from the usual excerpts I share from my memoir about my father’s family and art career. It aims to honor a matrilineal line for Mother’s Day—and expand the verb “mother,” maybe. There’s a lot to squeeze in so bear with me.

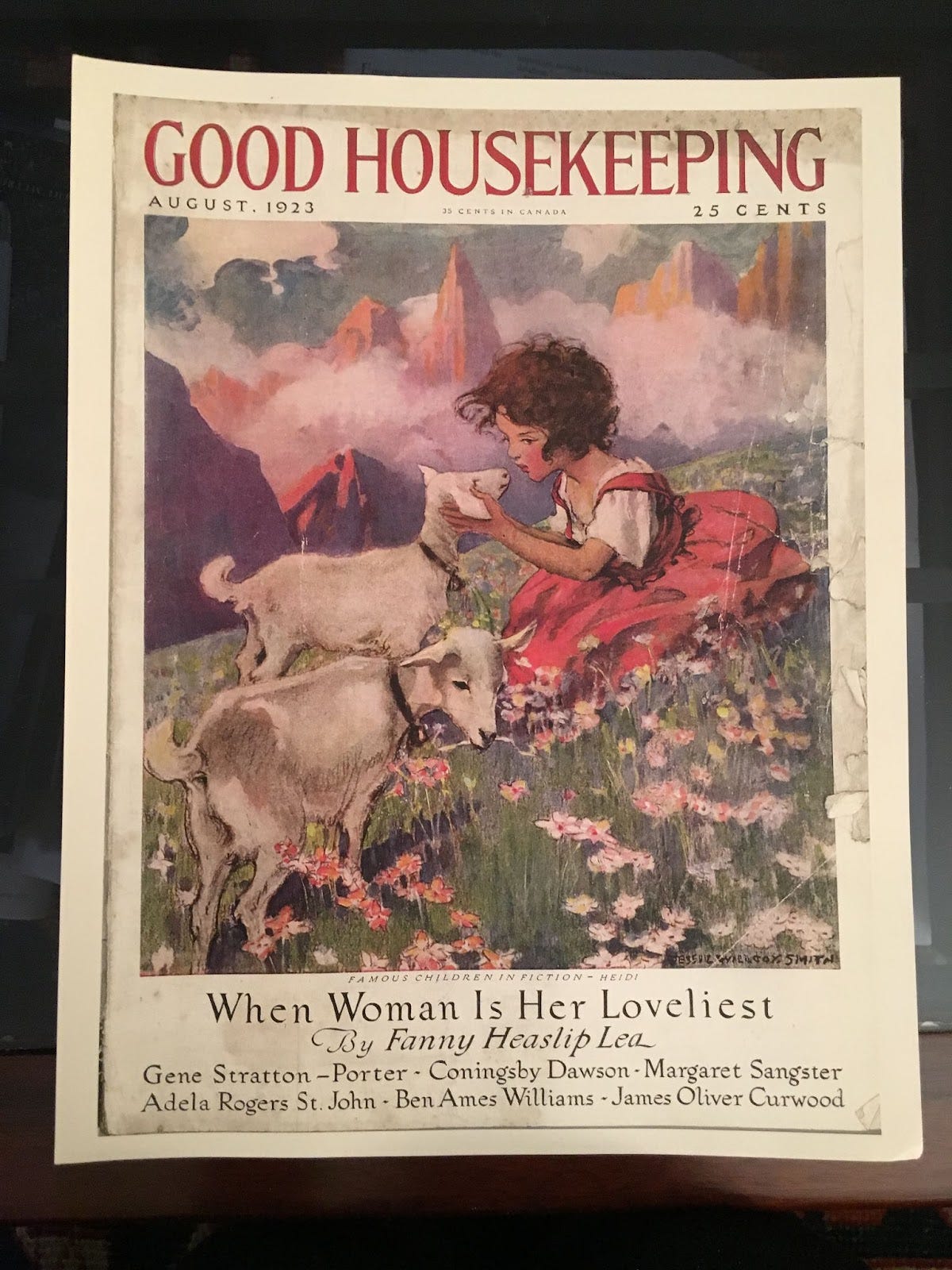

A rosy-cheeked girl with wind-tousled hair communes with baby goats in a field of flowers. There are picturesque mountains in the background. The palette is particularly eye-catching, with the red of the dress echoed in the pinkish Alps above and the scattered petals below. The angle too, on a hill, gives the artist a lot of room for an interesting composition on a sharp diagonal. The girl and one goat are in close conversation, eye to eye, while the other goat looks toward us viewers, bringing us into the intimate trio. It really is masterfully done.

This image was drawn from an illustrated edition of Heidi, the 1881 children’s novel by Johanna Spyri, and reproduced on the cover of Good Housekeeping in August 1923. The artist was Jessie Willcox Smith, a famous illustrator of children’s books and a frequent contributor to women’s magazines: that cover was one of 184 she drew for the magazine between 1917 and 1933. The model was my mother’s mother, Carolyn Jordan, aged 12. She told her daughters the story that she was in school one day and got called out of class to the principal’s office. She was afraid she was in trouble but it turned out that a local artist needed a female model with curly brown hair. Smith took many photos of Carolyn as studies and produced the illustrations the following year. My grandmother loved to tell her Heidi story. It was quite a claim to fame: to have been on the cover of Good Housekeeping magazine, to have worked with a famous illustrator, and to have appeared in a mass market book, to have been a heroine.

She was a beautiful child, my grandmother, as this studio portrait of her a few years later shows, so I can see why she was chosen. Those sausage curls were a signature look and that little pug nose made her look younger than her years. While I was growing up the guest room at my grandmother’s house was filled with Heidi portraits like the one below. There was Carolyn in a white nightgown, Carolyn hugging a tree, Carolyn reading a book, Carolyn sitting on a grassy lawn…. She wasn’t paid; when the book was published Smith gave Carolyn’s mother an inscribed copy, which is still in the family.

Smith was, then, maybe my grandmother’s alter ego. Both women were born and educated in Philadelphia. Carolyn even attended classes at Smith’s alma mater: the Philadelphia School of Design for Women (her daughters would remember their father calling it the Philadelphia School for Designing Women; later it merged with the women’s Moore College of Art and Design). Then their paths diverged. Carolyn married a Penn graduate just after the 1929 stock market crash. She raised four children and spent her life cultivating a taste for arts, crafts, and antiques.

Smith was one of several women artists called the Red Rose Girls by their teacher and mentor Howard Pyle. The women called themselves and their home Cogslea1, an amalgam of initials from their names: Henrietta Cozens, Violet Oakley, and Elizabeth Shippen Green, and Smith. They had met in art school and they lived together for most of their lives, sharing studios and homes. Smith and Cozens became lifelong partners. My family included female-dominated households too: from my own childhood after my father moved out to my Great Aunt Marie, who made a home and a life with another woman. The Cogslea women made professional success out of home-making and traditional “femininity”— becoming artists who specialized in children, gardens, and family life, though they chose differently for themselves. In a famous group portrait Green, Oakley, and Smith sit on the floor in artists’ smocks, each holding a long-stemmed rose. Above, Cozens “waters” them with a flower pot. They are cultivating a myth. Smith may have celebrated domesticity but she was an assertive professional: can you zoom in on the signature at the lower right of that magazine cover? It’s ALL CAPS in black lettering, bold as can be.

When I was growing up, my grandmother had a room in her house she called “The Doll Room.” It was filled with the china-faced, waxy-haired dolls she collected, along with her sewing machine and crafts supplies. Carolyn made each of her twelve grandchildren a crafted gift every Christmas. Once I got a metal bucket hand-painted with violets and embroidered with yarn along the handle. There must have been some present inside the bucket but I don’t remember now what it was. Another memorable year we all got brimmed hats crocheted out of colorful yarn and inset with tin cut from popular soda cans. There’s a famous photo of most of her granddaughters, ranging from three to twelve years old, in front of a Christmas tree wearing our cola, root beer, and ginger ale hats, and looking miserable. (Where were her two grandsons, by the way?) It was a bonding moment we can laugh about now— but I won’t embarrass my cousins by reproducing it.

In the essay “The Aesthetics of Blackness— Strange and Oppositional,”2 bell hooks opens with a long epigraph of memories of her grandmother’s home in Kentucky. Like my grandmother’s house, it was full of curated objects, reflecting a strong personality. She writes,

“Her house is a place where I am learning to look at things, where I am learning how to belong in space. In rooms full of objects, crowded with things, I am learning to recognize myself. She hands me a mirror, showing me how to look.”

I did not need my grandmother to teach me how to look because I had my father for that. But her house was memorable anyway. It is now that I realize one of the few objects I took from it when she passed away was the round American Empire mirror from her living room. I hung it in my living room. hooks concludes her essay laughing with her sisters about the gap between the words used to describe an interior (like “minimalist”) and the experience they have of a home. My sisters and I laugh together like that about our father’s house; my cousins and I laugh like that over that embarrassing photograph. Were the Red Rose Girls amused as they posed for that group photo? In other group photos the four women seem merry as they sit at a round table, lifting glasses. We are all knitting connections.

I’d like to write more about these matrilineal lines through art and family and how they transcend biological and legal categories of marriage and family. Maybe that’s my next project, thinking back through my mother. It would trace a line through women who weren’t biological mothers as well as those who were: me and my mother (neither of us artists) and her mother to women artists and writers, a continuous line of women making art with and for each other, from their own lives, bodies, and sometimes from the very conventions that constrained them.

Heidi was an orphan. In the novel, she was mothered by her grandfather and her friends. My grandmother Carolyn was raised by an indulgent aunt and uncle. Smith found her own family. “Mothering” is multidirectional and lifelong. I honor the recent loss of my mother’s older sister, another woman in my family who cherished art and beauty— and the mothering her son and daughter did for her until her last breath. I honor the mothering my husband is doing now for his mother, my beloved other mother, at a hospital every day. I honor my dear friends who take their moms to ultrasound appointments and pick them up from colonoscopies. I honor my sisters who brick by brick lay the solid foundation with me for supporting our mother (“am I only ninety?” she wondered recently, causing more of that restorative laughter). She and my mother-in-law are still taking care of their communities as matriarchal “kinkeepers.”3 I honor my children’s early efforts to take care of us, as they watch us taking care of our own parents. It takes practice and having a mirror helps.

Please like, share, or leave a comment! How have you mothered or been mothered? What does the word mean to you, beyond gender or biology or commercial holidays? I’m interested in your thoughts.

Resources:

A digital version of Smith’s illustrations for Heidi (1923). Courtesy of the New York Public Library.

Catalog entry for the Smith collection of photographs at the Library Company of Philadelphia. In 2022 I visited those archives, hoping to find documentation of my grandmother’s sittings one hundred years earlier– how exciting if I found extra images! Outtakes or letters or…. I spent a sweltering July day skimming Smith’s photographic studies of bonneted children and draped adults without finding anything like that.

A Calendly link for office hours so readers can schedule 15 minute introductory calls with me on Google Meet. No agenda needed, except to talk about research and writing— mine or yours. I’m just interested in getting to know you.

Here is a photograph of Cogslea from the Smithsonian’s Violet Oakley archive.

I can’t find an online version of hooks’s essay that isn’t paywalled, but the one on JSTOR allows for free reading if you make an account.

Fascinating. Jessie Willcox Smith and the Red Rose Girls are well represented at the Museum of the American Arts and Crafts Movement in St. Petersburg, Florida. Perhaps ypur mother is too, as a model. I thought I subscribed to you some time ago, and would have missed this post if not for Ann Kennedy Smith.

This is a great piece that has me thinking of all the interconnected women in my family, and in others. Some women did (and do not) have the opportunity to put their stamp on the world but have lived on through those they have raised, mentored, or educated. A great topic for a family history project. And these are incredible photos.