Dear Reader

On The Correspondent and letter writing

Dear Reader,

I recently read a novel called The Correspondent. It is written entirely in letter form by a debut author named Virginia Evans. Have you heard of it? I think it’s a word-of-mouth book that’s making the rounds. I didn’t love it, but it got me thinking—which may be even better than enjoyment—about why we write letters and how to use them.

For biographers, genealogists, and memoirists, letters are a gold mine and a gold standard for evidence. Not only do they often provide anecdotal life stories1 but they can display their author's unique voice and document their presence in some place and time. A letter from my father to his father reveals something about their relationship as well as when and where he was living during the year after my parents separated in 1970. A letter enclosed in its original envelope with a postmark is a wondrous find!

I’m sure you can see the structural problem though. The letter writer has mailed that letter, releasing it into the wild. So finding any trove of letters depends on someone else saving them. Unless you have both sides of a correspondence, which happens rarely in modern times, the senders tend to be documented by others. The savers may not be documented at all: we have only the letters they received. As evidence, it’s like using a photographic negative. My grandfather saved letters (so I have a sense of my father’s voice in 1970); my father did not (so I have no sense of my grandfather’s tone with my father). What does that too say about their relationship?

My mother has a paper folder labelled “personal letters” in her bedside table. It’s thick, but not fat enough to span a lifetime for a 91-year-old. I haven’t looked at them and won’t until my sisters and I inherit them. But I think the file may include some of her own letters that she saved when she had the chance. I think she once said something about her father returning her letters to him when she moved from home. I think. I don’t know. I hope. I barely knew that grandfather so even indirect, secondhand evidence would be very valuable.

I am lucky to still have my mother’s voice in my life, in person—but I am interested (as a biographer and daughter) in her prior moments, especially before my existence. I want that even though letters are usually a pose, a performance of self for a recipient or occasion. For my husband’s birthday this week I hand-wrote a card with a personal message, like I do most years; do I think someday someone will use this special event as a lens to interpret our whole marriage? It’s possible! I can accept that.

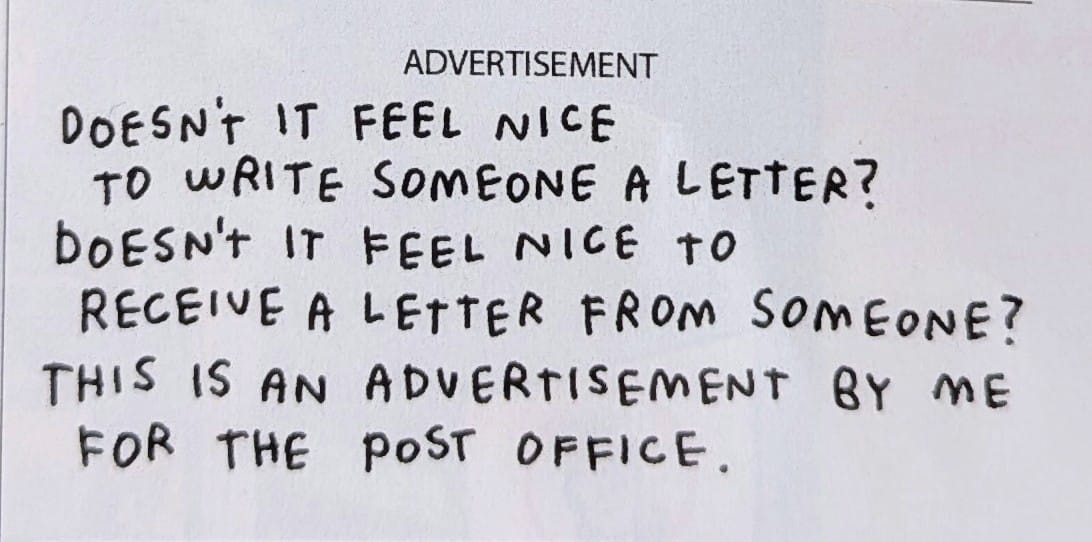

Maybe it was just to encourage us to think about writing as interactive, as reaching real people. Writing as letter-writing.

In The Correspondent I didn’t particularly like or trust Sybil Van Antwerp, the letter-writing main character., That’s as Evans intended: Van Antwerp was supposed to change over the course of the novel and she does. I was struck though by the inclusion of Van Antwerp’s correspondence with real-life authors. In a fictional context, this felt shocking. Van Antwerp-the-character writes to Joan Didion about grief, to Larry McMurtry about Lonesome Dove. Then Evans includes their responses; that is she writes back as Didion and McMurtry. This seemed like a remarkable sleight of hand, a magician’s trick! What was the point of it exactly? I wasn’t sure. Maybe it was just to encourage us to think about writing as interactive, as reaching real people. Writing as letter-writing.

When I taught expository writing the curriculum included a required essay to analyze “the essence” of an artist of the student’s choice. There was no right answer: each student just had to make a compelling case of their own about what made Scorsese Scorsese or Morrison Morrison. As an exercise on the way to the draft I would sometimes ask students to write something in the voice of their subject. To imitate. Sometimes it was just an in-class experiment, but it sometimes cracked something open. Like “oh, Woolf uses a lot of semicolons. That’s one reason she sounds like Woolf.”

Reading The Correspondent encouraged me to contact an author about her book, which I never actually do. I wrote to a Substack author I subscribe to about her most recent novel— and she did respond back, as the (real-life) writers in the (fictional) The Correspondent did. The exchange was satisfying, as both a reader and an author myself. I wonder how common that is. Do you write to authors with feedback? For no other reason than to start a conversation? (This too is a conversation with you!)

I am attending to all of this, I think, because I have to build a relationship with readers for Some Dark Force, the Victorian thriller I wrote with my co-author and friend

. It’s launching on Kickstarter now, then later in the year we’ll release the book to the public. Who is the I announcing the book, here or elsewhere? Maybe that I is really a she, a character, like The Correspondent’s Van Antwerp. Christina and I made an author video together but who were were trying to be? These questions seem important, if hard to answer. Those marketing materials are really letters to readers too— unknown and future readers.Thank you for being my reader! I enjoy being an author and writer here so much. Do leave a comment or share or write me and I will write back.

Yours, Victoria

P.S. This is not the first time I’ve written about letters. You can read about my birthday letter project below. That too was an exercise in interaction. What about you? How do you use or interpret letters, as genealogists, researchers, or just plain readers? What is the appeal of epistolary novels like The Correspondent?

The Birthday Letter Project

30 cards and letters (some handwritten, some typed), a collage of images from one sister and a book of memories from the other. Altogether, it’s an archive of about 3 linear inches.

I haven’t included a writing exercise in a long time, but this post seems made for one: write a letter to an author you admire about their book. Tell them something specific that you enjoyed or noticed about the writing. This is not an occasion to critique or to network but to share the magical experience of being a reader. Then, see if you can find the author’s email and send it. Or mail it to their publisher!2 Alternately, try doing like Evans: write a letter to yourself in the voice of an author you admire.

To be fair, not all letters are personal at all. Many letters, especially when that was the main form of communication, were just logistical. Most of the hundreds of letters I found by my biographical subject in Victorian England were just “about” arrivals and departures and train times….

Virginia Evans, aptly, includes her own contact information on her website. So if you’ve read her book, write to her! I should too.

Love the insight about the letters and why some may be interesting and some not, and for sure it's best to have both sides. This is helpful as I'm writing an "epistolary memoir" incorporating hundreds of handwritten letters, mostly from exes, and connecting them with my own memories. It's fascinating the different voices. Thank you for your post!

I really love getting emails from people who’ve read my books. I’ve set up a special email that I print in the back of all of my books. I encourage people to use it to share their feedback. I’m surprised by how rarely that happens, but delighted whenever it does.

It’s changed how I think about feedback too—I used to be very shy about sharing feedback, but now I go out of my way to share positive thoughts—when they’re genuine. I just think people deserve more positivity in their lives, so when I genuinely feel it, I try to share it.