Found and Found and Lost

In search of my father's paintings, part 1

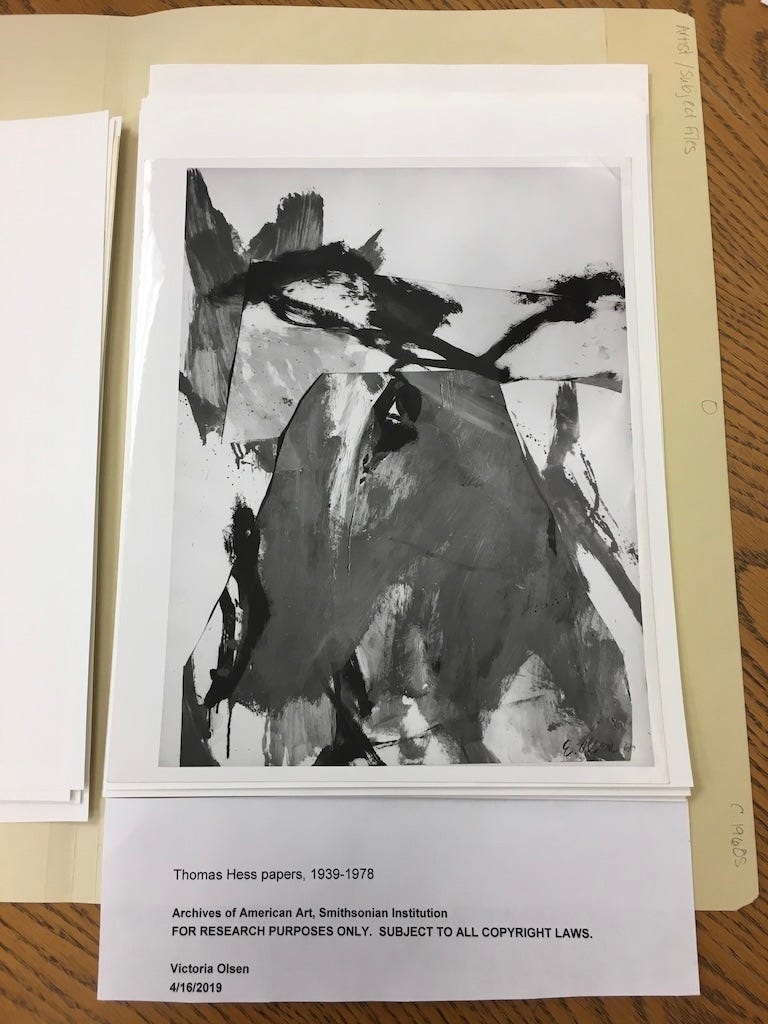

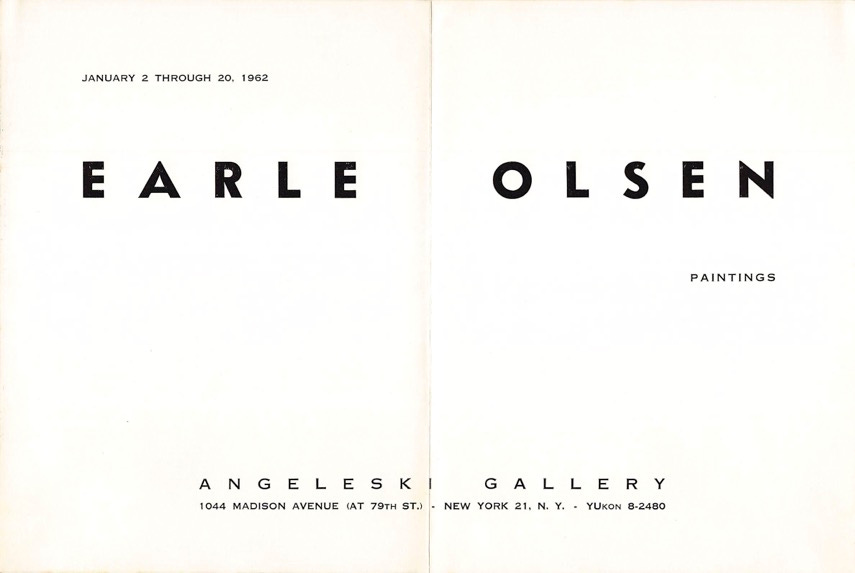

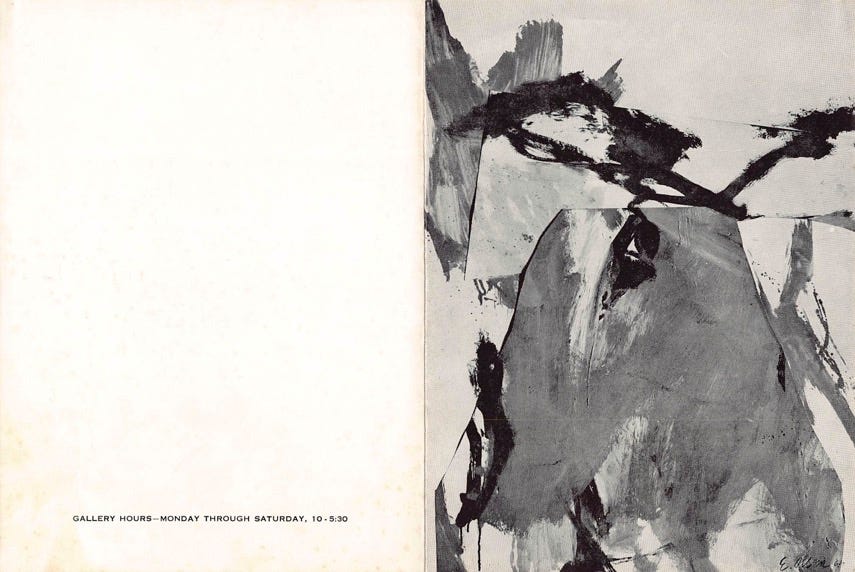

On an early research trip to the Archives of American Art in Washington, D.C. I stumbled on an untitled reproduction of a painting by my father among the miscellany filed under O in the Thomas Hess papers. Hess was the influential art editor of Art News in the 1950s and 1960s, but there was no explanation for why this reproduction was there. Later, I’d recognize it on the cover of an exhibition flyer for a 1962 show at the Angeleski Gallery, the last one-man show my father had in New York City. Eventually I found it again—after a search of my father’s name on eBay, of all places. When I saw it listed for sale—original work on paper, $1,500— I was shocked. How did it get there? It was being sold by a gallery in Hudson, New York, across the river from where my father had retired, but this work was from well before he lived there. I thought it looked familiar but it was hard to tell from the reproductions.

I checked the spreadsheet I had labelled “estate inventory” after we cleared my father’s house in Athens and there it was, though clearly I had forgotten all about it: “collage painting” found in “attic” and sold to “Patrick” for $300 in 2011. I do remember Patrick Terenchin, a curator and gallerist in Hudson, New York who bought several abstract works from my sisters and me. Eight years later, this was the only work he still had for sale on eBay and the discovery was unsettling, raising questions that were hard to answer.

Why did we sell those early works?

Because we had no room to store or display all the work we inherited and we had to choose. The early work was the most marketable.

Why didn’t we document that work better, by taking photos of everything we sold?

Because we forgot. My sister, a professional photographer, wanted to but we didn’t get to it.

Why didn’t I anticipate what I’d want later on?

Because I didn’t.

Should I buy it back?

This was the toughest one. My first reaction was dismay at having to pay five times what we sold it for to get it back. My second was anger at myself for everything that slipped through my fingers in those months: the file cabinets of business records I wish I had now, the oversized canvases we can’t find, these early abstract paintings.

But artists’ estates have particular challenges: unlike writers or musicians, the work visual artists leave behind typically takes up a lot of three-dimensional space. The Joan Mitchell Foundation has recognized this and started doing outreach to help artists plan their estates in advance. Even though my father never made sculpture or installations, the sheer volume of works on paper, canvas, and foam board was overwhelming, especially at the time. Later in my research process I would talk to another daughter of an artist my father knew in the 1960s: she had her father’s work organized in a climate-controlled room in her basement and was completing a catalogue raisonné of his work, while fundraising to mount exhibits. It was admirable—and way beyond my abilities.

The winter after my father died we spent hundreds of dollars a month on oil to keep the empty house minimally heated through the winter. To clear it for sale, we sold or gave away his Victorian furniture sets; we sent nine boxes of art books to a local auction; we stacked his poured paintings on the front porch and told neighbors to take what they wanted. I remember wanting it all gone. It was all so painful and so much to deal with. I had never dealt so closely with any death before and tried to just keep going. My sisters and I made choices and moved on, which is exactly what is so difficult about loss in general—the balancing act between holding on and letting go.

In the end, I decided to let my father’s 1961 collage go, even though it had some additional significance now that I’d found it in the archives. But my father’s work should circulate in the world. It deserved to be displayed and it was supposed to enter the public sphere. When I first drafted this that painting was still on eBay, waiting for its public. In August 2020, when I checked again, it had sold.

This is the first of a series of occasional posts where I track down my father’s art works. Creating a series like this is one way to organize your material and punctuate it with a rhythm, like returning to a heartbeat. In this case, it creates some suspense as well— what will I discover, and how, and where?

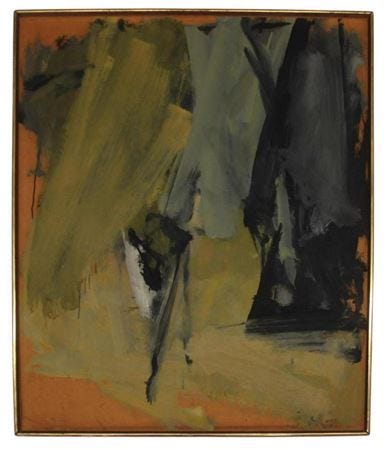

I’ve already published a photograph of another one that “got away” in auction, though most of these works are found, not lost, because we never knew about them in the first place. Every once in a while we locate others, like this one from last summer, which also had a label from the Angeleski gallery:

In future posts I’ll bring you along to a private home in upstate New York and to a college library, where two of his paintings are still on display. In the 1960s my father paid his bills by bartering paintings for services with therapists and doctors so some work spread without any “provenance.” I’ll tell you how I found some of those too.

Remember that I’ll eventually turn on paid subscriptions for access to these writing exercises as well as one-on-one editorial meetings with me. In the meantime, please comment and share around. Thanks for your attention!

Exercise: Is there anything that happens over and over again in your memoir or life story that you can make into a series? It could be celebrating a holiday or a trip that is made regularly— even to a local diner. It doesn’t matter so much what repeats as long as it gives you an opportunity to play with similarity and difference, which is a building block for art. To repeat, with variations, is to notice change over time, and show growth. It’s an experiment run in real-time and real-space— to investigate why the results might diverge. It’s inquiry and entertainment simultaneously. Enjoy!

Your family’s dilemma strikes a chord. My sister and I are now in our 70s; our children have limited appetite for our father’s work. We don’t have a plan and never took care of the art for reasons that ranged from simmering resentment of him (in my case) to sheer busyness. While our mother was dying, a gallerist in eastern Canada mounted a show and absconded with the work. I should have tried harder than I did to recover it. It’s not easy to inherit the estate of an artist, even a minor one.

What wonderful "finds," Victoria, but also what a cautionary tale, especially coming from a biographer herself. I look forward to hearing about the next legs of your "hunt!" You're setting up a suspenseful story for us.