I was cataloguing my father’s art books when I came across an inscription on the fly-leaf of Art Treasures of the National Gallery of London (1955). It read “Nov 7th Earle, with all best wishes, Alan.” Who was Alan? I had no idea.

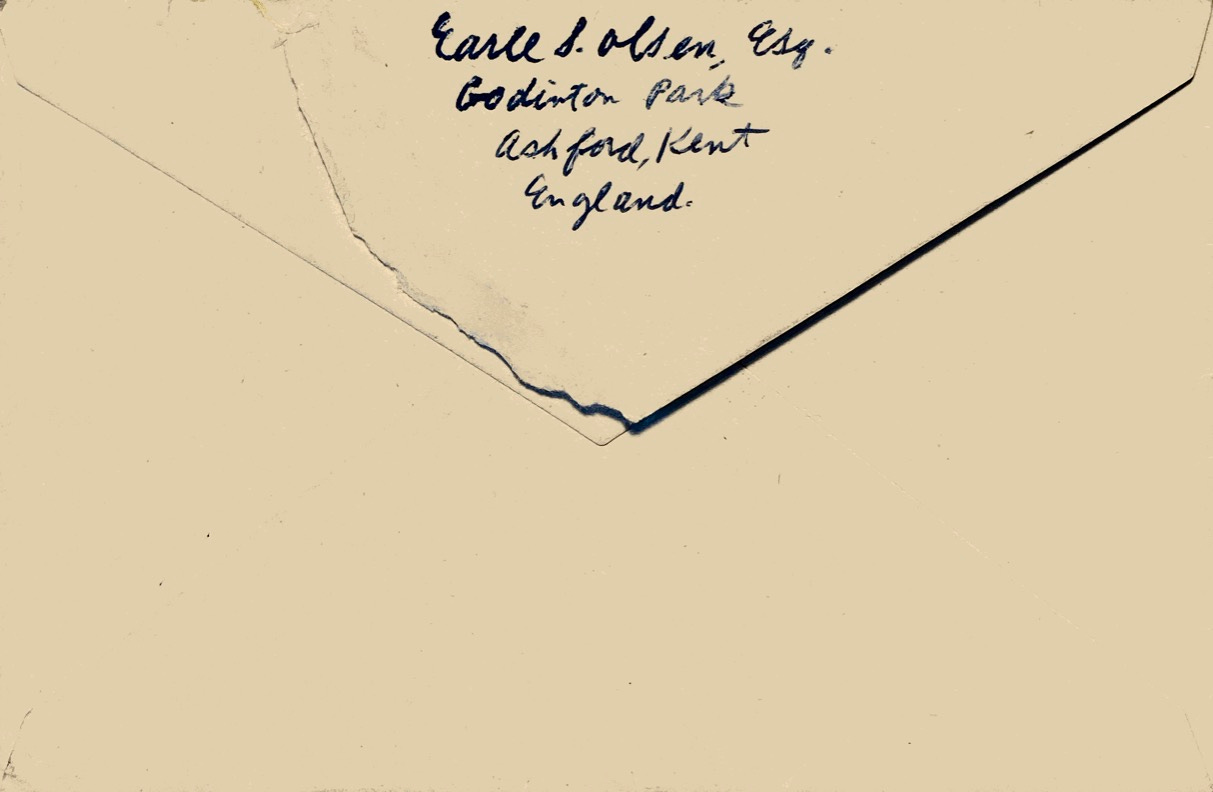

But my father had spent most of 1954 in Europe and my grandfather saved a few of his letters home. That July he wrote exclaiming over his visit to his friend Alan Wyndham Green, who owned an estate in Kent. He used Godinton House stationery and regaled them with his tour through Copenhagen (where the Olsens originated) and Sweden. I had never heard him mention any of this, except for the months he spent in Positano, Italy, which were hugely formative for him. When I looked up Godinton House, I discovered it was a 900-acre estate that had been established as a private trust in 1991 by its last owner, Major Alan Wyndham Green.

In the letter Earle meets Alan in London and orders a “heavenly” suit on Savile Row, then continues on to Kent:

“We drove down here in [Alan’s] wonderful green Jaguar car and now I am in another home that is also a magnificent estate!! I can’t begin to tell you of the divine gardens— (the trees and buses are clipped in different shapes— and there are thousands of flowers everywhere) and the house is so pretty with Sheraton and Chippendale furniture— and again wonderful paintings. There is a vista of rolling green hills from my bedroom— and I can see the Kent countryside for miles.”

My father sounds so young — and so happy.

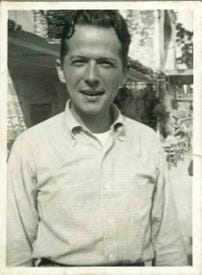

Later I found a passenger manifest for his return journey to New York on the Liberté, leaving Southampton on January 11, 1955. On it he had listed Godinton Park as his UK address. When I wrote to the estate, wondering what kind of archives or sources they might have from the 1950s I received three photos they had found, labelled “Earle.” One of them was my father, looking very young (see above). They had no other record of him— not as a guest nor as a friend of Alan’s. The archivist did find a reference to a postcard my father sent Alan in 1994, but it had disappeared. The timing was tantalizing — that is just when my father came out as gay to me and my sisters.

There was no reason to go to Godinton House, really. I had found everything there was to find already: there were no letters or diaries at the house, or in the Kent County Archive, no guest book to flip through. But I wanted to go, so I flew across the Atlantic and spent several hours there at the end of September, right before it closed for the season. It was charming, with twelve acres of landscaped gardens and a tea room.

Godinton House’s Great Room was built in the 14th century and passed into the hands of the Toke family during the reign of Henry VIII. The Tokes expanded the building piecemeal and held onto it until the late nineteenth century. It changed hands again before being bought by Lillie Bruce Ward, an heiress who collected art and antiques and renovated the gardens. Ward was close to her grandson Alan Wyndham Green, who served in World War II and then inherited the estate in 1951. Green died without family in 1996 and bequeathed the house and property in trust for the public; it has remained largely as he left it.

I walked the grounds on a uncharacteristically hot autumn day, then took a tour of the interiors. They didn’t allow photographs inside but the website has many good images of the carved wood staircases and cabinets of china, the family portraits and crests. It’s a Tudor mansion with add ons, so the architecture is more cozy than elegant. Still, it’s a helluva house. I understood why my father would have lingered there. It was less clear why he never would have mentioned it, or how he met Alan in the first place.

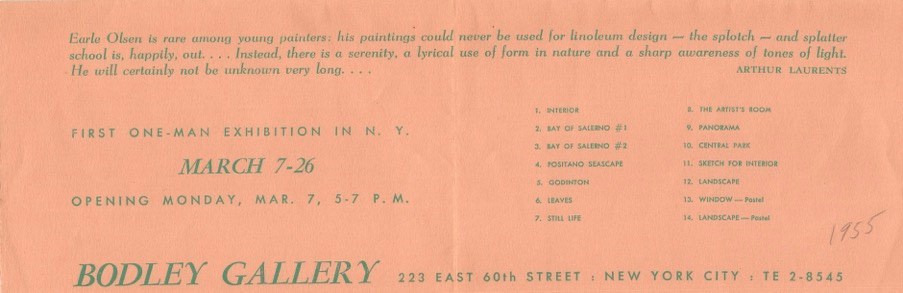

That year in Europe, when Earle sounded so happy, must have been productive and inspiring. He came home to New York with a slew of new paintings, which he parlayed into a one-man show at the prestigious Bodley Gallery in March.

Notice the painting called “Godinton.” I have images of many of those early 1950s works, but not that one.

What’s the takeaway from all this? I loved the trip, but there were no ghosts there. Or, more relevantly, there was none of my father’s art there, which would have been the best possible outcome. Here’s one imagined scenario, in the manner of the Three Stories I posted last week:

In 1954 Earle was an art school grad indulging in something like a Grand Tour, funded by his parents. He spent the spring in Italy painting and teaching at the Positano Art Workshop. He may have met Alan there (the photo above looks vaguely Italian to me— is that a Cinzano umbrella in the background?) and decided to visit him on his way home to the States later in the year. He and Alan were both World War II veterans, restarting their lives and newly freed from family surveillance. It could have been a romantic idyll.

Earle stayed at Godinton for months: maybe he painted some of his abstract landscapes en plein air in the gardens. He had, perhaps, gifted one to Alan. On the house tour I would turn a corner and be struck, dumb, by a familiar-looking painting. I’d gasp and lean in to identify the signature on the lower-right side. Earle with an e! Or just E. Olsen, with an e! My surprise would be obvious and the other tour attendees would clamor, “Really? Your father made that? How lovely!” “You had no idea it was here?” “1954? My goodness that was x1 years ago—”

Do I actually want to be a character in that scene though? Often when I get to this point in a fantasy, I balk. I don’t really want the attention after all. I just want some proof that my father’s work mattered. (If he left his family to pursue his art, then that art better matter— which means I’m slipping back into his cover story. After all, he left the family because he was gay— or rather, it’s complicated.)

I do get that reassurance that my father’s art matters sometimes, in some places, but those are other stories. If you’re new to this newsletter, welcome! Consider browsing my archive for other posts about my father and his art career, to put this one in more context.

Remember, I will someday turn on paying subscriptions and put some of this behind a paywall. I am not sure when or by what criteria. No writing exercise for this one, which is a bit of a road trip/detour from my usual posts. In the meantime, here are some other2, and frankly better, descriptions of visits to historic homes with famous gardens. These authors do an admirable job of linking the houses to their owners, creating an architecture of personality. I couldn’t quite seem to do that here, perhaps because my father stood in the middle.

Ann Kennedy Smith’s post Memories of a House, about Lucy Boston’s home and garden near Cambridge, which knits life, architecture, and writing together.

Alexander Chee’s post about visiting Knole, Vita Sackville-West’s estate, which isn’t far from Godinton in Kent. It’s a wonderful way to see the house through his eyes and I like that its queer history is visible.

In my fantasies I don’t have to do math.

When I refer to other posts, am I supposed to @ people on Substack, which would notify them that they are mentioned? I’ve done that in other posts but am not sure of the etiquette. Here I’ll try links instead. If I trip up, I hope someone will gently let me know.

"In my fantasies I don’t have to do math." 😂

That painting is beautiful. I'm looking forward to finding out what happened to all of your father's artworks - and if he was able to make a living as an artist?

We just found this story! My mother is 92 and was a friend of Alan's. She and my grandmother met him in Positano. Your father taught my grandmother to paint! He had a sister as well, right?