Into the Whitney

On art, family, and entering the archive

On February 11, 2020 my youngest sister M. and I showed up at the Whitney Museum of Art’s huge offsite storage space in Chelsea for an appointment to see our father’s most obviously successful work: the pastel called Orange Flowers that the Whitney bought from the Grace Borgenicht Gallery in October 1956. It has been in their permanent collection ever since, which made it the top line item on my father’s resumé. M. had flown to New York City from her home in the South of France for our mother’s birthday and we took advantage of her trip to see this work in person, though it had never occurred to us to do so before.

To view both the artwork and its paper records required three different appointments, made months in advance, but the Whitney staff had managed to make them all sequentially on one day. It was intense. By mid-February New York City was aware of the novel coronavirus and everyone was rattled. We didn’t yet know that it was already circulating around us. M. returned home a week later; by mid-March travel to Europe would be suspended.

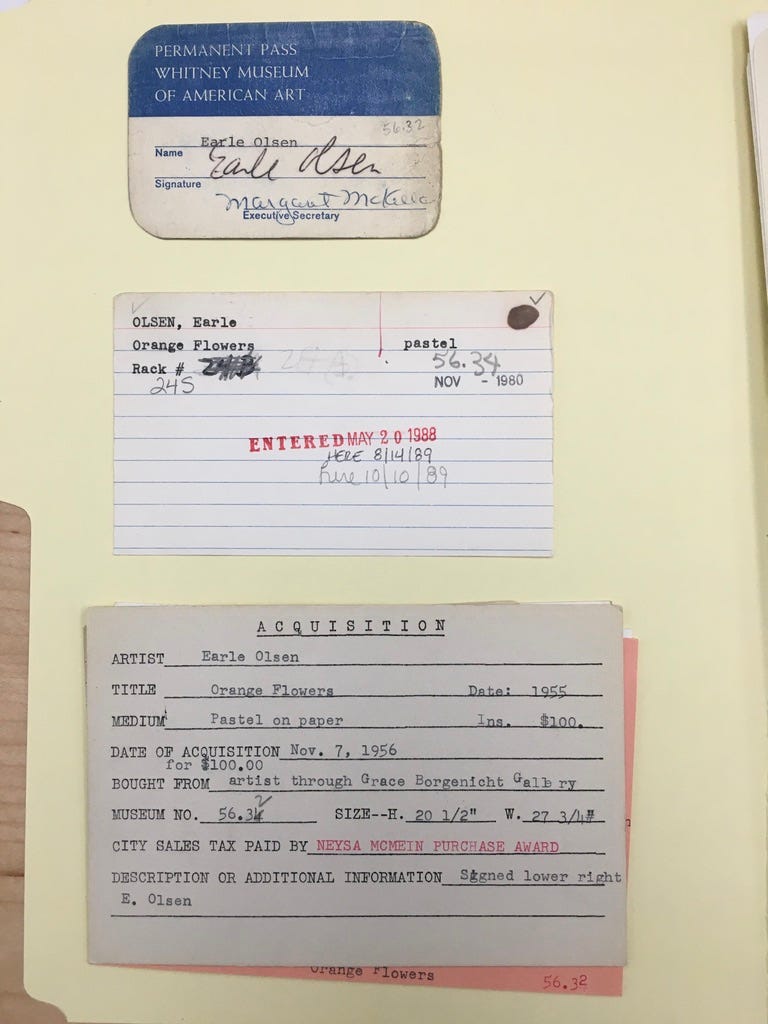

At the Whitney we started with the papers documenting the acquisition. M. and I checked our coats and bags in the narrow room and settled next to each other at a table with one folder at a time, pencils and laptops ready. It was probably the first time I had ever researched with anyone else, and I loved being able to compare notes with her about odd bits of random information, assessing them together. We studied the handwritten index cards and made notes of familiar names. We spent the whole morning there, finding nothing particularly new but reveling in the concreteness of the physical record. There he was, alphabetically located under O’Keeffe.

To see our father’s artwork itself, we were escorted upstairs to a different floor, through lime green containers on wheels and moveable shelving marked with bright masking tape. It reminded me of my father’s lofts, with concrete floors and exposed pipes. Then, anticlimactically, there was Orange Flowers, laid out on a drafting table, signed in the lower right corner. The conservator admired it as she flipped it over for us. We took photos and she showed us a pencil sketch on the back, where my father had drawn something that looked vaguely like a street map. We couldn’t read the words. And that was that. The two-dimensional work in three dimensions. The original. In person.

For our last appointment of the day, we walked a mile south against the winter wind off the Hudson River and entered the back door of the Whitney Museum on Twelfth Avenue. It felt both illicit and glamorous. We were ushered up to the documentation office, where records relating to the permanent collection are held. A file documented the purchase of Orange Flowers for $100 from the Neysa McMein Fund1. There were few items, but they were poignant:

• a card, signed by my father in the late-1970s, which allowed artists in the permanent collection free entry to the museum

• an index card with exhibition dates for when the Whitney loaned the work back to the Grace Borgenicht Gallery for his solo show in 1958

• a framing sticker for Robert M. Kulicke Frames, taken off the back of the work when it was put in storage

• my father’s obituary, which I wrote

• an email from my sister T., updating their records

• my own email, setting up this appointment for me and M., and the Borgenicht Gallery ledger page from the Smithsonian’s Archive of American Art that I had attached.

The Whitney visit may have unearthed nothing new about my father’s career but it revealed something new about archives: my sisters and I were now a part of them. Our emails, our interactions with curators, M.’s and my presence that day were now part of a permanent record. We were incorporated into it, in that etymological sense of “embodied.” Afterwards, I forwarded some tidbits to my father’s surviving artist friends by email, which would send more ripples into other archival currents. We are all already living our biographies.

I always enjoy research process pieces, where writers lift a curtain to show how the sausage gets made (to mix metaphors). Not everyone does, I know, and my memoir only does this a few times for a few trips—to Chicago, to the Smithsonian Archive of American Art in D.C., to the Museum of Modern Art, to interview some of my father’s old friends, and here to the Whitney. This story comes late in my memoir, as a sort of apotheosis. By then I’ve traced the relationship of art and family through my grandfather’s design work in Chicago, my father’s move to the New York City art world of the 1950s, and my father’s decision to leave his family and rededicate himself to his art in the late 1960s. This scene at the Whitney is meant to reintegrate those parts by showing, not telling, how art and family grew back together, how they were never really separated. I think it does that part well, but it’s also supposed to show off my father’s greatest success. And that part feels anti-climactic.

For one, I didn’t and don’t know how to respond to the art itself, once found. Orange? —yes, it’s very bright. The pastel looks pretty but I can’t think of anything to say about it. I knew my father had “a work in the Whitney,” but I had never seen it, even in reproduction, and never heard him mention it. Was it his best work, to account for its placement at the top of this hierarchy? Not to me, but what do I know? Overall, the visit was both a highlight—I loved researching alongside my sister!—and a disappointment because the artwork didn’t seem to matter after all. It should have been important, but it sort of wasn’t.

Instead, it was making this pilgrimage with M. that was deeply moving. As adults, we three sisters have been close except in geography, and we have always spent a lot of time together with art. When we’re in New York City we meet at exhibits, as we used to do with our father and still do with our mother too; that’s normal. In fact, I now see all of that time in art spaces as a kind of healing. The family had divided over art and now we could bond around it. The trip to the Whitney was a major milestone in that process (for me, I can’t speak for M.), though I’m not sure the excerpt makes that clear. I left out other parts of that day that made up its connective tissue— our lunch at Chelsea Market, our stops at other galleries along Tenth Avenue.

As it turns out, that trip represented the high point of my research, just as it represented the high point of my art father’s career. Over the next few months, as COVID-19 spread and my extended family relocated out of Brooklyn, my research trips dried up. Our family reunion, scheduled for June, was canceled, like everything else. I didn’t know this yet, but I wouldn’t see my sisters in person for over a year. I would see my mother every day, as we isolated together in a pandemic bubble.

Now, when I reread this excerpt it seems to be about presence—mine, my sister’s, the artwork. My father’s art had been nearby all along (or nearly—the Whitney had moved from the location of my childhood on Madison Avenue. Perhaps the storage facilities moved too.) The presence I sought then, of course, was my father himself, because he had been gone for nine years by then. Emotionally, this scene is really about loss, not finding or searching. The real finds were the traces left behind that I didn’t know to look for—those handwritten index cards, the annotated catalogues from exhibitions long forgotten, the insurance claims and shipping receipts. These point to the everyday business of the art world, moving stuff around from place to place, in and out of storage, invisibly. Orange Flowers remained invisible too—it never made it onto a wall at the Whitney. But I felt as if my sister and I, by showing up, disrupted the archive—if only a little bit—to insert our family into it. Then, the last step of reintegration, for me personally, is always this—writing about it.

As always, please like, share, or comment. I appreciate and respond to all feedback. At some point I will put the exercises behind a paywall but for now I encourage you to write your own version of a research process story, if applicable to your project. If you share any of it in the comments, I will respond to that too!

Exercise: Tell a story in a few paragraphs about a research journey in which you are yourself present in the scene in the first person. Focus on the action: where did you go? Who did you meet? What did you find, but also what did you not find? How does this piece change what you thought you already knew about your story or subject? Remember, you don’t have to include this in your larger project. It can just stir your thinking in a new way.

Resources: Two memoirs that follow a daughter as she researches her father’s creative work include Lilly Dancyger’s Negative Space about her artist father in the 1980s and Ada Calhoun’s Also a Poet about her art critic father’s interrupted biography of poet Frank O’Hara. In both cases we tag along as the researchers uncover and evaluate evidence about their fathers—and tell their own stories. Recommended!

Like my father, McMein was an alum of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She was a successful illustrator for Saturday Evening Post and McCall’s magazine covers as well as ads for products like Palmolive and Betty Crocker. When she died in 1949 she left money to the Whitney for annual purchases of art. The museum purchased 72 works with her funds in 1956, but own none of hers.

Less than six degrees of separation. Oh my. My father’s pinnacle is also a painting in the Whitney. And he studied at the art institute of Chicago

I loved this essay and I also liked the painting. And I am fascinated by how you and your sister became part of the archive. I've not done any archival research myself and this made me want to start now!