Scroll all the way down to read about a new feature I’m rolling out for readers….

“Victoria? It’s Winston. I knew your father. I used to talk to him on my cell on my way home from [garbled]. I want to talk to you.”

The day I received that voicemail, Wednesday March 18, 2020, I had driven from Brooklyn to the Upper West Side of Manhattan and picked up my 86-year old mother and her rolling suitcase. Then I drove across town to the East Side and picked up my mother-in-law and her many tote bags and house plants. Then we drove for five hours to Cape Cod, where we reunited with my husband and our two children, our dog, and a van filled with our computer gear, coolers of food, and luggage. Then Winston called. I had tried to reach him six months before, to no avail. I had left a message on Facebook, which must have finally sifted through. And there he was.

Winston met my father Earle at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC)1, which they both attended on the GI bill after serving in the Navy during World War II. When I started writing about my father’s art career I combed his address book for possible contacts and found Winston. My father had died in 2011 at age 84; in 2020 Winston was 92 years old. On March 18th, as the novel coronavirus caused shelter-at-home restrictions across American cities, the independent living facility Winston lived in near Chicago closed its doors to visitors, canceled all events, and started delivering meals to rooms. Over the next three weeks he left me eighteen messages. “I’m in a very lonely state of mind,” he’d say. “I’d love to be talking to somebody.”

“Can you meet me?”

I called Winston back the next day but after ten minutes of yelling into the phone he still couldn’t hear me. We’d go around in circles. “Do you want to come up? I’m in room 222. Second floor. Do you want me to meet you at the front desk? I can’t hear you!” We would try again. Then again. In the driveway of my house I picked up a third time: “Victoria Olsen? It’s Winston. Can you meet me? I want to meet you. You like me? I like you too. I want to meet you.”

“I’M TOO FAR.”

“Too fat?”

“TOO FAR. I LIVE IN NEW YORK CITY.”

“I love New York City.”

He’d get about every fifth word. “You don’t have a car? Oh. What shall we do?” Silence. Then it would start again.

“You know me through your daughter?”

“MY FATHER!”

“What’s his name?”

I shouted some more then hung up, weary.

Eventually I did have actual conversations with him, though it was hard to stay on any track. I learned very little about my father and a lot about Winston. He talked about art books, offering me his extra copy of a book on Egon Schiele’s landscapes: “It’s a good size book. It’s well illustrated. If you would like it, it’s yours. It’s got plenty of illustrations by the Austrian artist. I’ve got that to offer you.” I sent him the biography I had written of the Victorian photographer Julia Margaret Cameron. He thanked me gamely. He often said my father was “a good guy,” but never got close to what I wanted to know: details about their art classes in the 1940s and insight into my father’s decision to leave Chicago for New York City in 1951.

In an effort to get more information I wrote him a letter with photos and questions. I considered trying to set up a video call. “You’re welcome to come over to my place, messy as it is,” he’d say. “Please come over. I want somebody to talk to.” He knew that his meals were in his room because of the virus, but he continued to expect his daughter to come Saturdays to take him to lunch.

Can anyone be lonely when we all are?

When I was still a full-time writing teacher I assigned parts of Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City to my students. In the book Laing discusses her experience moving to New York City alongside interpreting some contemporary artists of solitude, like Edward Hopper and David Wojnarowicz. Her questions resonated during the pandemic: for example, can anyone be lonely when we all are? Aren’t we always alone in relation to society as a whole? As COVID-19 infections escalated across the country, my therapist told me that anxious people can get less anxious when their anxiety is normalized (a new spin on the “generalized anxiety” diagnosis). When everyone feels anxious they feel validated instead of excluded and stigmatized. By “they” I mean “I” and “we.”

What is intimacy?

That March we brought our mothers to Cape Cod to hole up with us to protect their health and prevent their isolation. Six of us. Two from each generation, in some kind of parody of Noah’s Ark. My husband and I, in the middle, ran errands and the rest stayed in, working virtually or bored. We walked the dog off leash and cooked. I’d go running; once a lone coyote crossed my path. Sometimes we ran into people on the beach and waved from afar.

What is intimacy? Is it physical touch? Presence? I held hands with my mother, especially when she walked the dog with me, tapping her cane along the empty country roads. I tried to remember not to touch my own face.

My mother and I fell into a pattern of morning video chats with my two sisters, who lived thousands of miles on either side of us: one to our East in Southern France and one in the Midwest on a Great Lake. It was better than a phone call; we became a tight knit group, like we were in the old days. When my mother felt a flash of fever my husband and I mobilized quarantine protocols, donning face masks and rubber gloves. She had no temperature but we watched her carefully, isolating her in her room and interrogating her on her symptoms. “When are you going to let Grandma out?” my younger child asked, and the next morning Grandma was liberated. I didn’t tell my sisters, and the video calls resumed, as usual. Is intimacy verbal?

”This is Winston. Who are you and what do you want from me? Hello?”

Of course talking is powerful. Transference. Confession. The trading of secrets and the sharing of inner experience makes one vulnerable, which is an essential ingredient of trust, and through trust to intimacy. Winston told me about his sons, about his daughter, about his wives. I heard about his homes in Chicago, the watercolors he sold in the 1950s, the girls he necked with at the lake near where he grew up in Michigan.

“You wrote me?! I haven’t gotten it. I got your book. The type is kind of small. Your father was in the Navy right? I was in the Navy in Jacksonville for two years. I was an artist and did cartoons for the newspaper, then a billboard. It’s hard to talk on the phone. You wrote me a letter? That’s wonderful. I sent you pictures. Have you seen my picture? Where are you? Massachusetts?! That’s where my cousin is. He’s a brat. He started chasing me and my aunt spanked me for making him mad. If I send a picture maybe you’ll fall in love with me. I’d love someone to fall in love with me.”

During his calls I took notes, which stretched to six single-spaced pages, though the conversations and memories all ran together. Gradually the calls tapered off. Days stretched between voicemails. He never seemed to have gotten my letter—or at least he never responded to it. I never learned anything new about my father. Maybe that was never the point. Instead it was a tenuous connection to another person, almost random in their remoteness from me. I’d love someone to fall in love with me. One of my friends read my manuscript and said that sentence haunted him. It haunts me too. It reminds me poignantly of my father’s “coming out” scene in 1993. “Everyone deserves love, don’t you think?” he had asked me.

I never learned anything new about my father. Maybe that was never the point.

All through that pandemic summer I imagined driving to Chicago to visit Winston —just to make him real. I imagined talking to my father about the old friends we had never met or heard about. Eventually I searched online and discovered that Winston had passed away in January 2021. I still have his voicemails saved on my phone.

During those few months of contact my sister found a Facebook message Winston had sent her when our father passed away:

“I am very sorry to hear about your father. I knew him from the SAIC. I remember he visited the painting class of P. Weighardt, [who said] ‘So Earle are you a big shot New York artist now?’ I know he kept painting until recent years. He is rightfully proud of you and your sisters…. Winston”

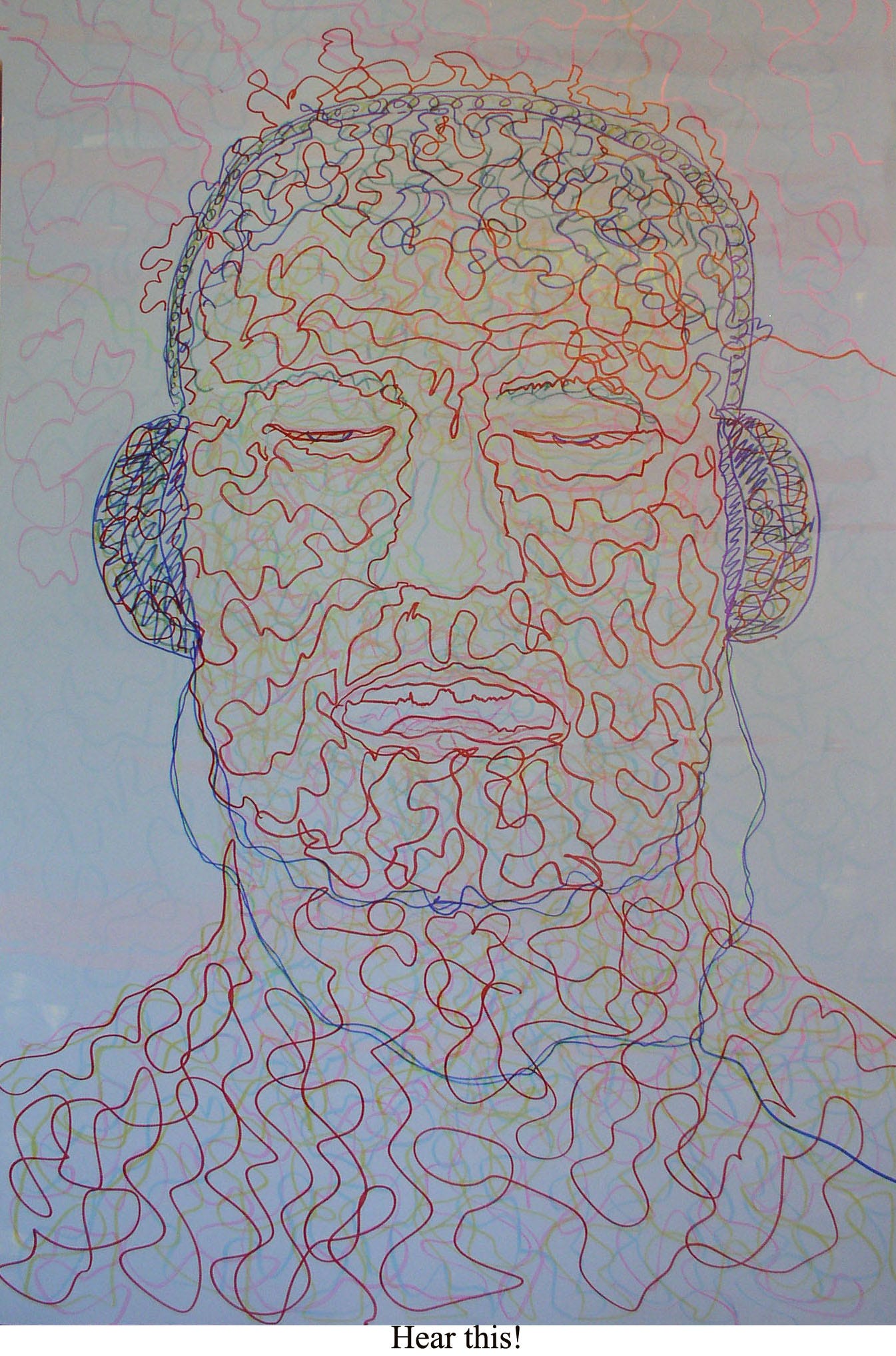

There’s so much pathos here— in this story about my father’s return to Chicago, in Winston’s loneliness, in the retreating memory of the pandemic itself, which we haven’t really “gotten over.” Now, the titles of my father’s artworks included here seem prescient: Hear this! Hello out there! Those faces, drawn in magic marker, anticipate our unraveling selves. Like this post, they are lines thrown out into empty space.

Thank you for listening! Please like, comment, and share. Sharing builds connections— online and everywhere.

Writing exercise: Imagine the negative space around something you didn’t do, someone you never met, somewhere you have never been, and draft a scene that describes it concretely, with dialogue and setting.

SPECIAL ANNOUNCEMENT!

In the spirit of connection and experimentation, I am adding regular Office Hours to this Substack so you can sign up to meet with me to talk about your writing— or introduce yourself. For now, they will be Friday mornings (ET) on Google Meet but I can adjust that. The sessions are free and I encourage you to use them for anything writing-related. In the future I will reserve these times for paid subscribers and offer longer sessions to work on writing pieces together. Working one-on-one with writers is a part of my teaching life that I really miss. Click here to sign up!

Hello out there! You have captured the yearning of lonely old age, which swamped so many during the pandemic. I saw it on social media, where people revealed their true quivering selves as never before; in a virtual presentation I gave, where the q&a vibrated with desperation; and in my own writing from that time, which I recently reread. In four years I had forgotten so much. It’s not simply that we don’t understand what happened and what the long-term consequences will be. I don’t think we want to remember.

I really enjoyed this post and found the story about Winston very moving. Thank you.