When you don’t know where to start, start wherever you are. So today’s post is a tour around my desk. Prepare yourself for some clumsy amateur photos— this is an improvisation one morning, one day, today.

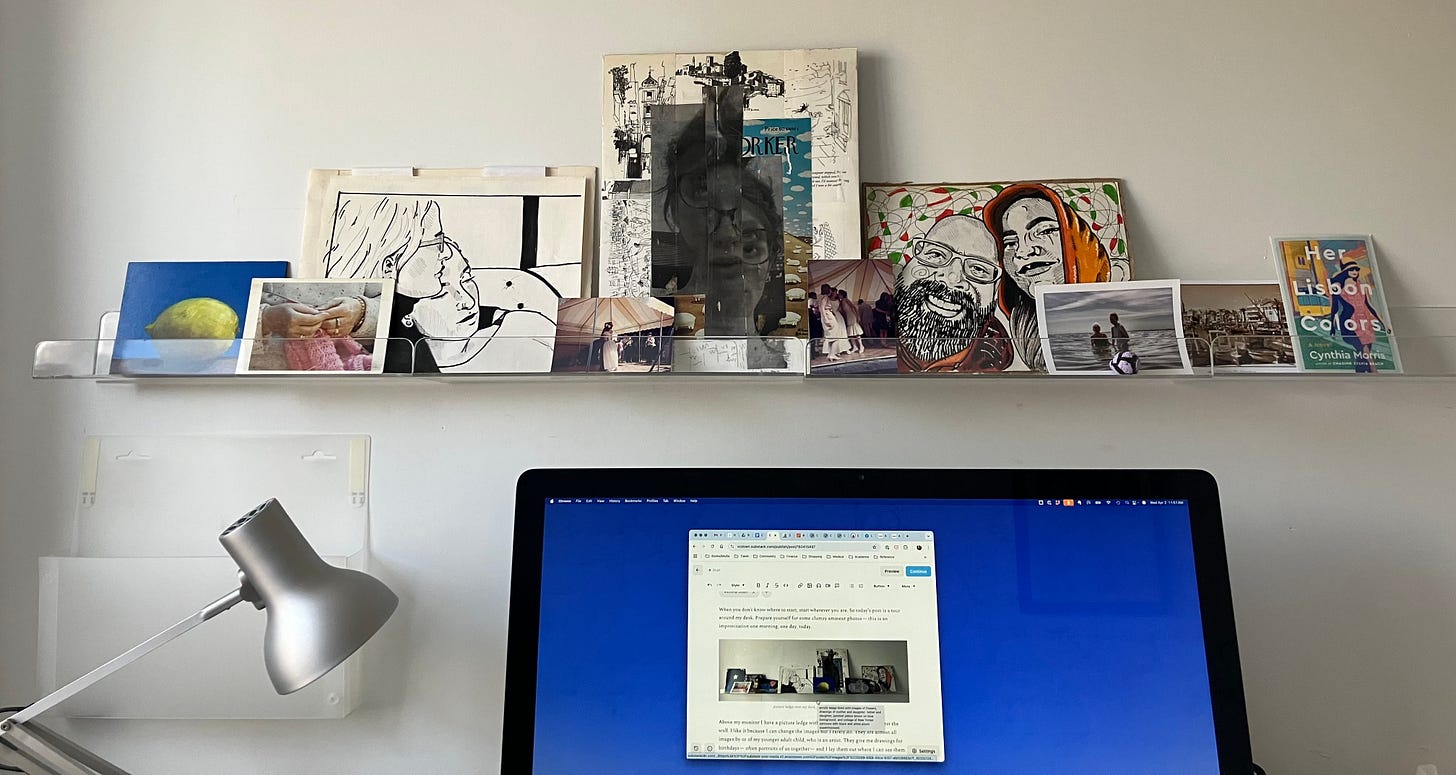

Above my computer monitor I have a picture ledge with scattered works leaning against the wall. I like it because I can change the images but I rarely do. They are almost all images by or of my younger adult child1, who is an artist. They give me drawings for birthdays—often portraits of us together—and I lay them out where I can see them. The ledge also includes an image by my photographer sister and a small still life of a lemon by a former college professor of mine. Each piece is meaningful to me.

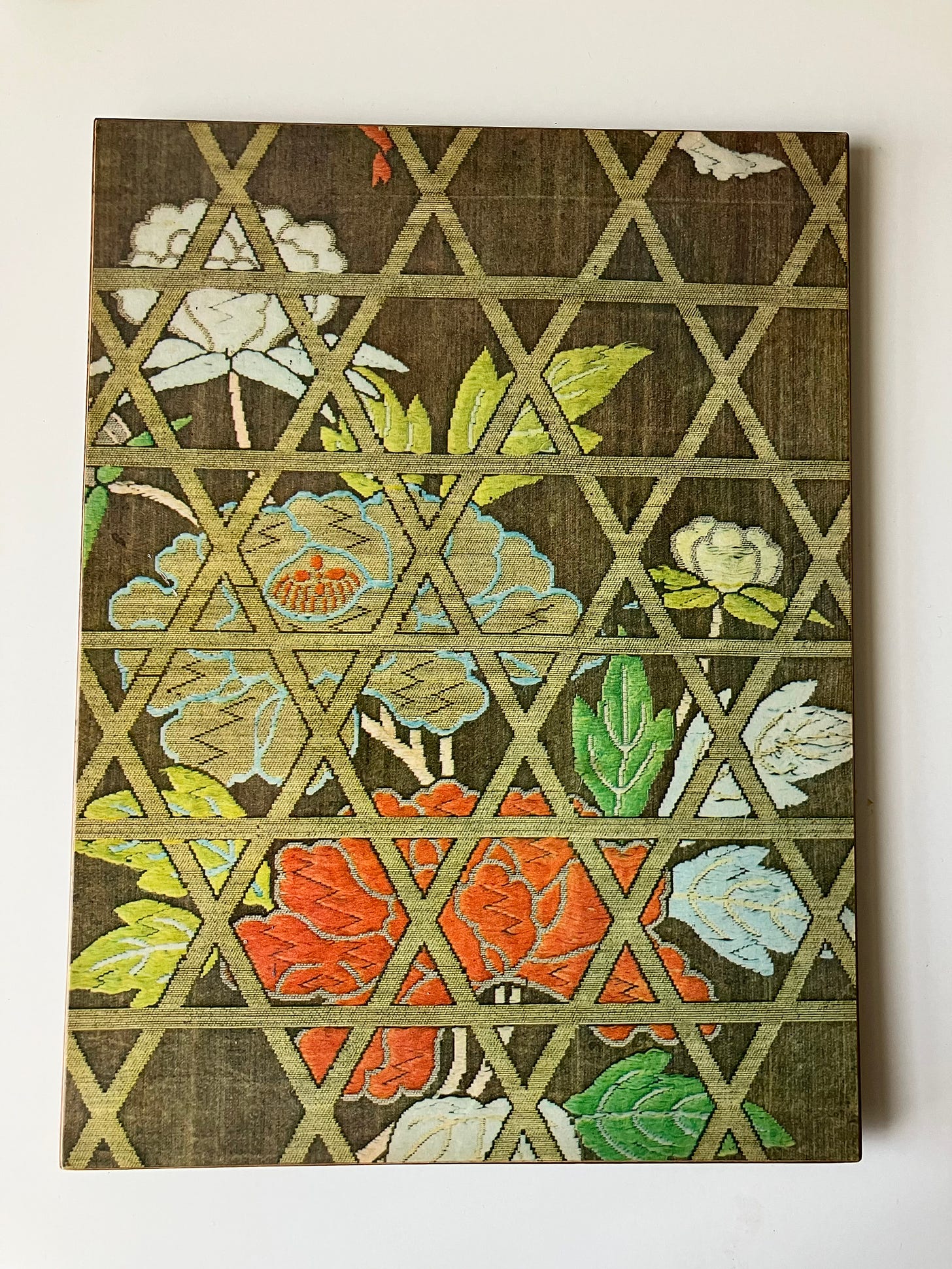

At the very far left side, though, are two floral works I propped up there. They are reproductions mounted on hard board and designed to either hang on a wall or stand by themselves. They have an ingenious paper backing that can pop out to form a stand. I found three of these in a box of stuff from my mother’s apartment and just sort of claimed them. I don’t own them; I have them.

All three are labeled KULICKE, copyright 1970 on the back, with the company’s then address in the East Village.2 My father worked for Kulicke Frames from about 1963 to 1979. (I wrote about his career there here.) The company, a pioneer in art framing led by artist Robert Kulicke, moved around a bit and I remember as a child visiting my father at an office on lower Broadway. The firm specialized in innovative mass market frames, like plexiboxes and plastic-wrapped posters, ready to hang. My parents were friends with Bob and Barbara Kulicke until both couples divorced in the early 1970s.

Where am I going with this? I am not sure. I started out wanting to return to close reading and visual analysis. In future posts I would like to return to closely examining some of my father’s work, but for today I’m less ambitious. Just starting here, at my desk. The three floral pieces are not exactly special for me— I have no specific associations or stories for any of them but I have many general impressions. They used to live in our kitchen, which is visibly evident with some splatter and grime on their surfaces. They go way back.

Let’s look at each one, briefly.

I haven’t cleaned any of them. I’m embracing mess.

This one is very similar to a blue-purple enameled brooch of a pansy that my mother has worn for years. Bob Kulicke ran a jewelry studio for decades that specialized in cloisonné jewelry. I looked at the pin more closely recently and asked my mother if Bob had designed it. “Yes,” she said, “your father gave it to me.” Come to think of it, these floral pictures are probably some of the last things my father left in our apartment when he moved out. They were left behind.

This one looks like an image of embroidery, doesn’t it? The cropping of the flowers behind the trellis-like grid is surprising. I wish I knew where these images originated.

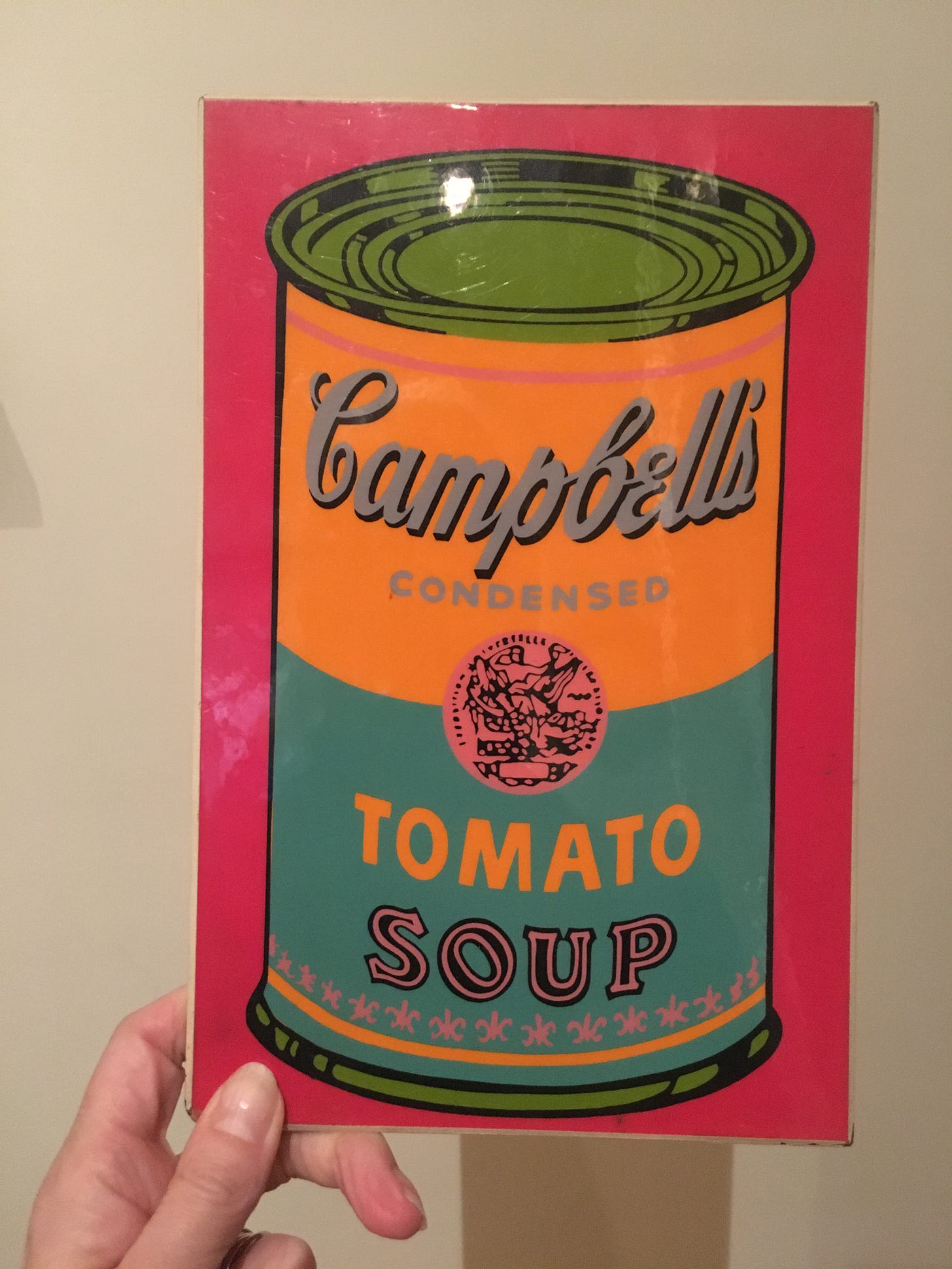

And here’s another Kulicke reproduction not on my desk. This one still sits in my mother’s kitchen. I took three photographs of it and will include the middle-messiest here. My fingers are showing, but my hand looks unusually well manicured. You can see a little gleam of clear nail polish, as well as a smeary spot on the picture and a burst of reflected light. I hadn’t bothered to wipe this one off either. I didn’t position it on a table. My polish is growing out.

This is Warhol, of course, another artist who—like my father—came from the midwest to New York City in the early 1950s to make it in the art world and succeeded wildly, another gay man who navigated the closet very differently. My father took a different path, disdaining Pop Art and ambivalent about the limelight. These soup cans were Warhol’s first foray into Pop Art in 1962. Tomato Soup was Campbell’s first soup, sold in 1897. Both my father and Warhol would have grown up on those canned soups, as I did until Progresso’s minestrone eclipsed them in my house. Warhol said, “I used to drink it. I used to have the same lunch every day, for 20 years, I guess, the same thing over and over again.”

Repetition. His soups. Our grilled cheese sandwiches. Art objects, well used.

I think I’ve processed these archival pieces enough. It’s time to make something new of them, for the new month and season. So here’s a rehanging of my picture ledge, using only objects I found in my office. It’s more of a stepped pyramid shape now, instead of the skyline it was before. I added a postcard received from a subscriber that I haven’t acknowledged yet (thank you, Suzanne! my response is late because I’m working on it) and a postcard for

’s forthcoming novel— in a fresh spring palette. Bright colors anchor each end of the display.I moved my spawn’s bird drawing onto the window so it can hover over a tree. I added a photograph to the ledge of me and my mother in Cape Cod Bay, like a double baptism. And two photographs from my wedding in 1990— of me and my husband dancing under a tent and of me and my two sisters, whispering together. There’s no need for more of my father on this picture ledge. He’s visible everywhere in the house *except* my office, and invisible here in so much writing.

This is enough for today. But I’ll end with another meta moment about my writing itself, the kind of section I used to include regularly but haven’t recently. I’ve been thinking about my teaching though— because a former student contacted me out of the blue and because my husband recently asked me about how I taught “idea'“ for essay writing. “Idea” was a big word in NYU’s Expository Writing Program when I taught there, and a necessary element for an essay. In this context, an Idea is not a topic like Climate Change or a theme like Colonialism in Literature. It’s not a position, like being pro-choice, or an argument, like asserting that “photography made representation in painting unnecessary.” It’s bigger than a concept or a claim (ie. “numbered lists drive clicks”) and smaller than a generalization (“information should be free”). But it overlaps with all of these. We taught Idea as a set of interlocking concepts that knit together external facts, research, and observations with internal impressions and feelings. It’s what makes an essay cohere. Your idea is always YOUR idea so it makes an end run around the typical student anxiety about coming with “something new to say” about Hamlet, for example. You can always find something new to say about anything if you combine objective and subjective elements persuasively, without skimping one or the other. You just (just!) need to work on choosing interesting pieces and connecting them.

The essay above is a first draft, written in one morning. It intertwines some external evidence (confined to the art on my picture ledge) with a bit of storytelling (about my childhood and parents) and associative thinking (about memory and art). It doesn’t flesh out the connections well enough, but there are seeds of ideas here. About repetition as a way of connecting past and present, and providing emotional comfort. About embalming memory in everyday objects. About lowering expectations for creative work to get something messy out there. Like this.

Thank you for reading and sharing and commenting! I so appreciate it. Do you have objects that go way back that you never really look at? Is your desk clean or messy? Mine really isn’t messy in the usual sense. It’s my mind that feels cluttered right now.

This child called themselves “SPAWN” in a letter to me so I’ll use that name for them here.

There is no credit or copyright for the artists of these pieces, only the framer. Maybe Kulicke also produced the art.

I loved this meander through your desk art even before I saw my novel’s postcard in it! It’s so fun to peek into someone else’s world through their art and ephemera. Plus the craft tidbit at the end about the ‘idea’. Thank you for this ‘draft’ and the ‘amateur’ photos. Fresh and interesting as always.

I need a ledge like yours, for beloved images stained by life.