Plexi Man, Part 1

In which I share an excerpt about my father's art on plastic

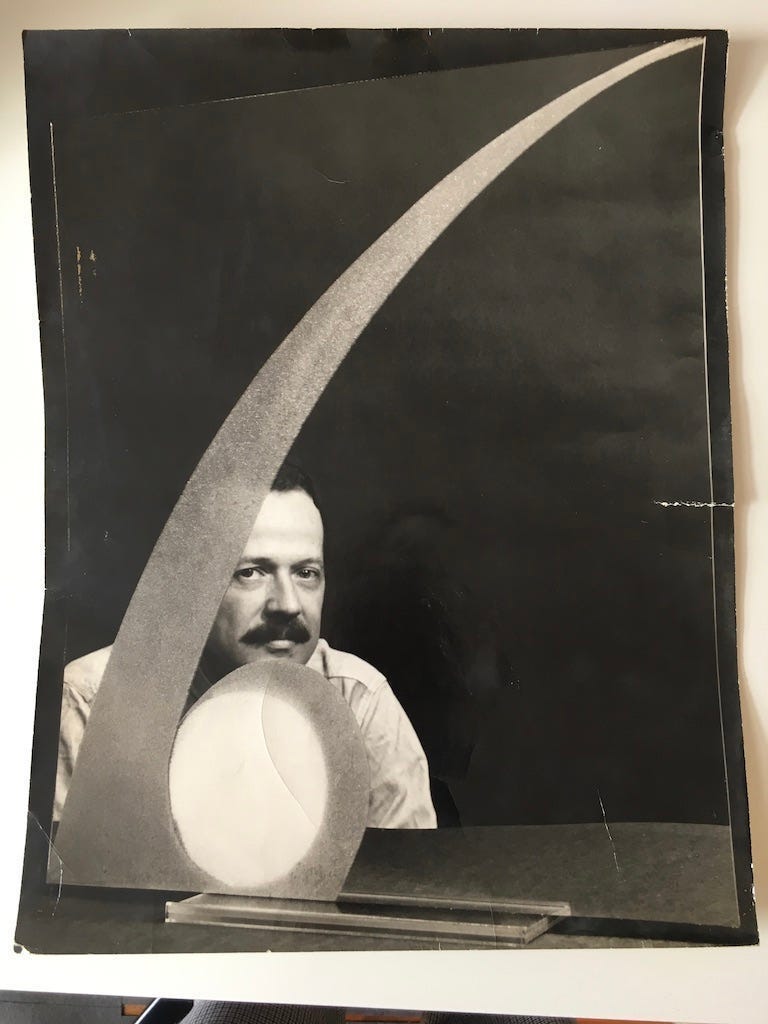

When I look at this portrait today my father looks wary, a little hunched. He’s so familiar (family) but this was before my memories start. One can’t tell the blue of his eyes, a grayish shade my youngest sister inherited. This photo too is damaged, as you see from the tears and folds. I carried it upstairs with a load of clean laundry, tucking it under my chin because my hands were full, and snapped a photo of it with my phone. As an image it’s crooked and the layers are visually confusing — my father peering at us from behind his own Plexiglas artwork, itself at an angle to the table it rests on.

The photo curves off the white desk I lay it on, and that sliver at the bottom edge reveals the gray carpet and wood floor beneath, which mimics the slivers within the photo: the geometries formed by the diagonal arc, like my father’s right shoulder…. Which is when I realize that this is not a photograph of my father sitting behind a spray-painted piece of clear Plexiglas but a portrait of my father in the mirror of his own artwork. Because otherwise my father’s shoulder would reach to the edge of the black background, right? On my left the sun streams through the window across a stack of folders. If I’m literally bringing the past into the light, reflecting on reflections, it’s all too obvious.

“Plastic” is a cliche about the 1960s. The Graduate immortalized it before the decade was even over. But the word covers a lot of ground. Plexiglas, for example, is actually a trademarked version of a thermoplastic made from a chemical, polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA), discovered in the early 1900s by the same kind of German emigré who revolutionized paper products by inventing cellucotton. Otto Rohm wanted to strengthen glass so he laminated it with PMMA and ended up creating a transparent product called acrylic. In 1933 the stable, scratch-resistant, shatter-proof version was trademarked as Plexiglas, but other companies, like DuPont, trademarked other versions, like Lucite. These products were first used in the war effort for aircraft windows then spread into the consumer markets. In the 1940s Laszlo Moholy-Nagy at Chicago’s Institute of Design was one of the few artists experimenting with the material.1 Moholy-Nagy made paintings on transparent plastic in the 1930s, a concept my father and some Op Artists would take up again in the 1960s. I keep one of my father’s table-top plastic works on a window sill: like most of his few remaining works on Plexiglas, it is spray-painted with geometric stripes in bright colors that let light through. A larger abstraction of intersecting green and blue shapes on Plexiglas hangs in my foyer.

By the time my father was working with Plexi he was living in Englewood, New Jersey in a suburban house on a tree-lined street with his wife and three young daughters. He commuted into Manhattan for his day job designing and selling picture frames for Kulicke Frames. The company was founded and run by the artist Robert Kulicke and his wife Barbara, who were also friends of my parents. Bob Kulicke loved frames. After serving in World War II and graduating from a Philadelphia art school, he studied with an art conservator in Europe and was an expert in fabrication and historical styles. He was also an innovator (in interviews he often insisted that he was a designer, not an inventor, because he developed ideas that had been tried before). Picture frames had been made of wood and carved and gilt for centuries, but Bob experimented with plastic and metal, creating lightweight and unobtrusive frames that kept the viewer’s attention on the art itself. Kulicke’s frames were also economical and could be sold in modular pieces instead of being custom-ordered for each specific work. It’s not an exaggeration to say that those frames transformed the art world. Kulicke’s obituary in the New York Times ends with an interviewer claiming that “the name Kulicke was like Kleenex in the frame world, a standard.”

Kulicke revolutionized the framing business by re-packaging art. The Abstract Expressionists exhibiting in midcentury New York City worked on huge canvases. It’s hard to tell from reproductions, but in real life a Jackson Pollock action painting, for example, takes up a whole wall of a huge room. Kulicke Frames made those oversized canvases lighter and less expensive to frame. They also suited the new art style, which would have looked incongruous in old-fashioned wooden frames. In his oral history for the Smithsonian archives Bob Kulicke said that Kline and Motherwell wanted their frames narrower and narrower until the wood wouldn’t support the pictures and he turned to aluminum. To de Kooning he finally said, “shut up it can’t be made any narrower.”

Later, the company rolled out the Plexibox, which encased three-dimensional objects in clear, sturdy boxes. In a sense, the Plexibox turned everyday objects into art; the plastic stood in for the glass vitrines used in museums. My father used a Kulicke Plexibox to display one of the Kleenex boxes his father designed, a meta moment worthy of a Borges story: a plastic box turned a cardboard box into an art work. That box may have been the same one displayed in the 1949 “Modern Art in Your Life” exhibit at MoMA2, though I found no installation view where it was visible. By the 1960s it could be protected by plastic from the very dust that the tissue was meant to wipe away.

To sort through my father’s art and photographs is to find the KULICKE sticker everywhere. Earle worked at Kulicke Frames for nearly a decade, though his relationships with the Kulickes and the company were volatile. My father’s friendships were always full of dramatic ups and downs. He took offense easily and held grudges—as did his friends. He quit and rejoined Kulicke Frames over and over, and dropped them (or was dropped?) completely when he left to start his own picture framing business in 1979. On an early resume my father claims co-credit for Kulicke’s revolutionary frames, and it seems credible that he might have had input, but there is no documentation for his version of events. My father would have been competitive with Bob for other reasons too: Bob was a more successful painter and turned the company over to his wife in the mid-1960s so he could devote himself full-time to his art. He too divorced and we saw no more of the Kulickes after that, though Barbara and her children lived a block away from my mother on Riverside Drive. Their son Michael had carved his name into the cement sidewalk near our apartment; I walked past that bit of historical evidence for years after he must have grown up and left home.

The move to New Jersey in 1968 frayed both my parents’ marriage and his job at Kulicke. In retrospect, they moved to the suburbs from the spacious apartment on Broadway that my mother loved because that’s what their peers were doing. My grandparents Andrew and Elsie again gave them money for the down payment (what had happened to the money given in 1964 to buy a townhouse that fell through? My mother doesn’t remember.) My youngest sister M was born in April and by June they had bought a house in Englewood and moved in. My mother remembers being aware almost immediately that it was a mistake and the letters she and my father wrote to his parents in Chicago bear this out. The house was much more work to maintain than a rented apartment: it needed repairs and redecorating and garden upkeep. My mother worked part-time so they brought an au pair with them to help with the three children under four years old. They acquired a dog. They had no friends there. And both of my parents added hour-long commutes to their jobs in the city.

To make things worse, up the street lived another artist more successful than my father. Richard Anuszkiewicz was an Op Art pioneer about my father’s age, doing similar geometric work on Plexiglas and canvas, but he exhibited with the high-profile Janis Gallery. We only lived in Englewood for two years, from when I was four to six years old, and I remember the chestnut trees, being bitten by our dog, playing with one of Richard’s daughters, and my father’s resentment of her father’s success. When we moved back to New York City in 1970 my father gave up working in plexi and left his marriage.

This week’s post comes in two parts. Tomorrow I will analyze this excerpt from my memoir Daddy-O and give some behind-the scenes account of my efforts to find that photo by Namuth. Stay tuned! If you have any feedback or comments, please share! I’ll respond.

My father was an art student in Chicago in the late 1940s but I don’t think he encountered Moholy-Nagy. He did own a copy of Vision in Motion (1947) though.

I like this section a lot. The tension is building, especially in the hints at your father's ambition and perhaps thwarted desires for success as an artiist.

Thanks! It’s strange to present them like this, out of order! But giving me ideas too--