Cracker Jack and Me

An Olsen family myth, analyzed and with an exercise

When choosing an excerpt from Daddy-O, my memoir about my father Earle Olsen’s art career, to share this week I tried to find something Thanksgiving-related. This was the best I could do— just because it is sort of about food [shrug emoji?] and takes up stories we tell about the past. I acknowledge that I wrote and shared this piece from the ancestral and traditional homelands of the Wampanoag nation.

When my father was dying in an Albany hospital my sisters and I tried to get him to talk a little bit more about his father’s design career, but it was too late. Earle was 84 years old and recovering from brain surgery. In a short video recording I took with my phone we hover around the bed, prompting him.

My sister: “Your dad worked on some famous products, right? Like Cracker Jack?”

Earle, eating chocolate ice cream: “Oh yes. Cracker Jack. Morton Salt.”

My sister: “Can you tell us about them?”

Earle: “Sure.”

Long pause while he focuses on the spoon.

We gave up.

While I was growing up, my father’s stories about his father’s success as a commercial designer in Chicago had a swirling cast of characters, but the star was undoubtedly Cracker JackⓇ. In what I consider the “classic” package design (ie. the one I grew up with) Sailor Jack and his dog Bingo face outward and Jack salutes us. My father always claimed that his father Andrew P. Olsen designed the Cracker JackⓇ box and the boy and dog were based on his older brother Andrew Jr. and their dog Rex. My father told that story so many times that it even appears in his friend James Harvey’s oral history for the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art.1 (In other words, it’s in an archive; there is evidence.)

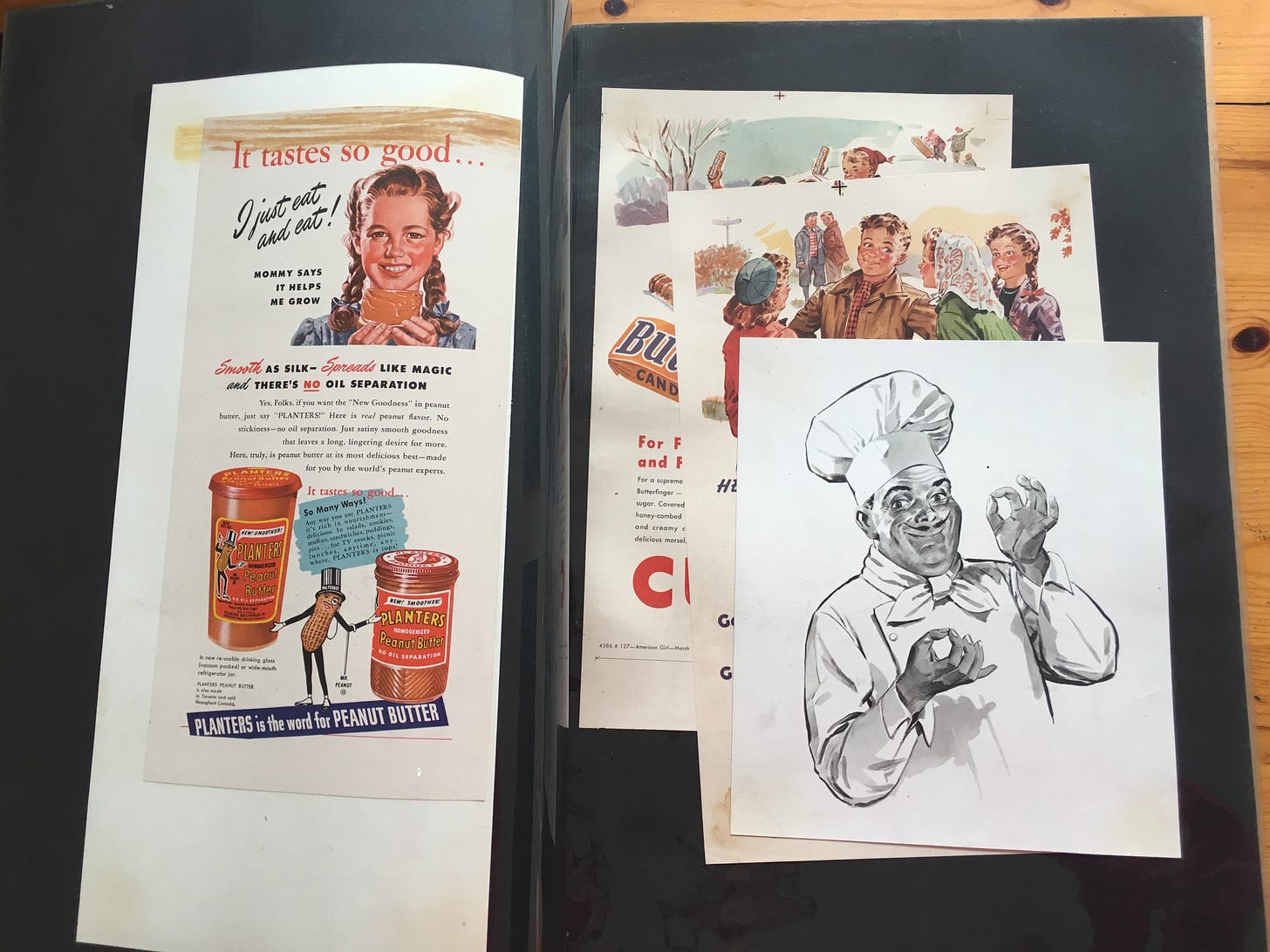

My grandfather’s professional portfolio spent decades in my father’s attic, then another in my basement. It’s a black book filled with clips and awards, and mottled with mold spots. The items may never have been carefully mounted but now they are a mess: coming loose from the glue and crumpled. They include flyers for the Commercial Solvents Corporation as well as print ads from national magazines like Vogue and package demos for Kleenex boxes in the 1950s. The earliest clipping is an ad in the Saturday Evening Post for Dr. West’s toothbrush kit in December 1929, when my father was three years old. The products range from International Cellucotton products (the precursor to paper company Kimberly-Clark), Abbotts Laboratories vitamins, Sendra gloves, Planters Peanuts, and Allstate insurance. Most of these were Chicago-based companies. My grandfather also documented every award he ever received; even the fifth place certificate for “five and ten” packaging is carefully saved.

There is not a single image or reference to Cracker JackⓇ.

In searching for evidence for my family’s story, this photo is all I found. My father is the boy standing on the right in the white sailor suit. His older brother, curly-topped, holds their black and white dog in a similar position to the pose in the ad, with the dog between his legs. They may be at Pennelwood, a family resort where they spent many summers in cabins on a small lake in Berlin Springs, Michigan. My guess is that it was taken around 1933, when the boys were about six and ten. Photos of sailor outfits are surprisingly common in our family albums—and my grandfather and father did indeed both serve in the Navy. In one photo Andrew Sr. stands on their front lawn with both of his sons in sailor gear. In another, young Andrew Jr. stands at attention, saluting in a naval cap. In yet another he wears the same kerchief as Sailor Jack, which raises the possibility that the photos themselves were studies of some kind.

However, Cracker JackⓇ tells their own origin story. The company was founded by Frederick William Rueckheim and his brother Louis in Chicago; they sold the candy at the World’s Columbian Exposition there in 1893. They later added Henry Gottlieb Eckstein to the company (his contribution was the wax-coated inner lining that kept the candy popcorn fresh). In 1908, when “Take Me Out to the Ball Game” was released, Cracker JackⓇ earned its now indelible association with America’s favorite pastime. The iconic package, still more or less in use today, emerged during World War I; the boy and dog were registered as a trademark in 1919. The company claims that the boy was a grandson of Frederick’s who died at age eight in 1920. The dog was a stray Eckstein adopted.

You can already see the problems this story poses for my family’s version. Andrew Jr. wasn’t even born until 1923 so how could he have inspired a package design trademarked in 1919? My grandfather Andrew Sr. was indeed active in the Chicago advertising world by the 1920s but the best we could argue for our side is that he could have worked on the package design for the cardboard box in the 1930s, not that he created the figures. Yet the family story was so specific! The dog, the sailor suit, the brother. Why make it up?

Besides, the model’s death feels a little too neat, doesn’t it? It’s a cliché ending for a sentimental story about a candy swathed in nostalgia, which the baseball anthem reinforces. Even in 1908 the song lay the foundation for an American mythology: sunny days, leisure, and simpler times when all you needed to do was “root, root, root for the home team” and count to three strikes. Even today the company’s ad copy emphasizes nostalgia and memory, claiming that it tastes “just as good as you remember. And…who can forget the thrill of opening the surprise inside?”

My father loved childish things, like candy (and root beer, incidentally), as much as he loved that Cracker JackⓇ story. When we three were kids we’d all happily sing “The Candy Man” song as we bounced off the leather seats of his vintage cars, stuffing gum wrappers into the ashtrays of their doors. He was that candy man, making the sun shine and the world taste good. When McDonald’s started appearing on the East Coast in the 1970s we stopped at a drive-thru en route to my dad’s summer house in Greenport, Long Island, getting frosty shakes, several orders of French fries, and apple pies. Sweets were a huge part of any time spent with my father, and a big reason why we loved those party-like weekends with him after the divorce. (These details too feel sentimental now. I am recycling nostalgia.)

That excerpt was one of the first pieces I wrote in my memoir, when I still thought of it as a book about two generations in commercial design and fine art, when it was still as much about Andrew as Earle. Maybe you can’t tell from this bit but there was too much research. I digressed into the rise of advertising firms in Chicago, early 1920s campaigns for cigarettes and soap, and the stories behind other “mascots” like Chef Boyardee, Mr. Peanut, and the Morton Salt Girl (who was also appropriated by my family sometimes, but who had no real life model).

My story focuses on the candy and the past instead of the emotional core: my father’s brother Andrew Jr. He was the Sailor Jack; he was the family member who died at age 21, while training to be a pilot during World War II. My father’s nostalgia for childhood and the good old days was rooted, to use the song’s verb, in that devastating loss. I approached that family story as an academic, interested in ideas about popular culture and eager for documentation. But why did my father re-tell that story over and over? For the feelings— of grief and connection to the past. Memoirists need to find the emotional core of their stories. This helped me to understand something else: it doesn’t matter if the story is true or not.

What is “true” about ads– or family stories? Both begin somewhere, with a claim usually based in something factual, but drift away from their “sources” (in the sense of corroborating evidence, but also origins). In my family, these origin stories were all intermingled, and characters like Sailor Jack and the Morton Salt Girl were more real to us than the family members we never met— like Andrew Jr. My father left his hometown of Chicago and hardly kept up with anyone; the brand names with those little Ⓡs became part of our family tree.

What’s missing from Andrew’s portfolio—the Cracker JackⓇ boy, the Morton Salt Girl—seems just as interesting as what’s there. Is it too much to interpret the Cracker JackⓇ story as a way to hold on to Andrew Jr. and Rex? Maybe. Where my grandfather packaged consumer goods, my father ended up packaging art itself: he earned his keep as a picture framer. Earle made a custom Plexiglas box to encase the cardboard box his father had designed for Kleenex brand paper tissues, and kept it on display in his living room. That was the public legacy, packaged in stories retold and boxes reframed. But he kept Andrew’s portfolio moldering in his attic and never showed it to anyone.

Eventually I intend to keep the memoir excerpts free, but put some of the analysis and exercises here behind a pay wall. For now, everything is free and I encourage you to try the exercises that follow the critiques and see if these posts can help you structure your memoir, clarify your meaning, or just generally tune your writing skills. Feel free to share your exercise below in the comments— if you want feedback please say so and I will respond to it. I appreciate any likes, shares, or comments!

Exercise: Write a paragraph or two describing a central myth in your memoir and trace it back to its sources. It may be a family tale like this one, an origin story, or even something assumed but never talked about. It can be big or small. Then do some research or analysis: Where does the story come from? Whom does it benefit? Why does it matter to you or your story now? And, finally, what happens if the story isn’t true?

(An example of a memoir that looks at a family story through art history is probably Edmund de Waal’s Hare with the Amber Eyes (2010), which traces several generations of the Ephrussi family through their collection of netsuke figurines. I wrote about a Jewish Museum exhibit based on the book here. I’ll be collecting and posting a Resources page for these references soon.)

Harvey, himself the package designer of an iconic box (the Brillo soap pads package that another Andy made famous), repeated the story as an example of successful package design, claiming that the Cracker JackⓇ box had been honored by the Museum of Modern Art (that’s wrong, though true of Andrew’s design for yet another cardboard box—for KleenexⓇ. Stay tuned to these pages for more on that box!).

I keep coming back to this phrase: “You can already see the problems this story poses for my family’s version.”

It’s so punchy and direct— it pulls me in as a fellow detective in this story.

This too: “Yet the family story was so specific! The dog, the sailor suit, the brother. Why make it up?”

It’s funny to me now that no one even thought of confirming the story while my dad or grandfather was alive. That too says something about its function --