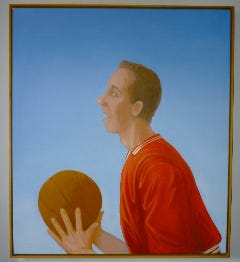

In the 1980s my father, who had spent his early career devoted to abstraction, turned to a series of portraits he would call his “Blue Sky” or “Human Comedy” paintings. These were not the first portraits he ever made, but they were the only series. The subjects were taken from the parade of faces my father saw around New York City at the time, or from newspaper clippings that struck him. With their focus on uniforms and gesture, the individuals can seem like “types” — and I think that’s what my father intended by the Human Comedy title. But they were also formal compositions, playing with a limited palette of primary colors and a constant blue sky background. There are at least fourteen of them, though I’m not sure I’ve counted them all.1 I’m not sure why he stopped; perhaps his interests just drifted off to the next thing. He didn’t speak much about his process.

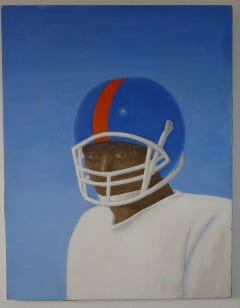

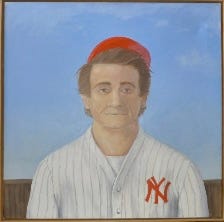

The woman in yellow, above, echoes a classic three-quarter portrait format, like the Holbein paintings my father loved. I admire the flatness of this composition and the balance of colors. The football player (below) reduces that classic format even further— removing the clouds and even the lower face, which is literally guarded. In contrast, the baseball player seems wide open and squared-off, but his blankness is still ambiguous. The Yankees logo provides a bit of context the football player lacks (though I know my father modeled him from a photograph of a New York Giants player).

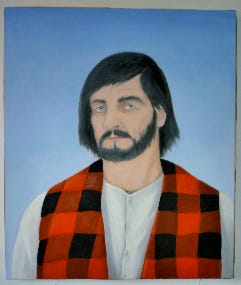

Some of the Blue Sky works do have more personality than these, which seem intentionally generic. The man in the red-checkered vest (below) is one of my favorites because his expression is so striking. He seems engaged in some dispute with us, wary and skeptical. His eyes are off center, his mouth flat. Similarly, the man in the Jamaican hat looks back at us with some reserve. His faint frown is highlighted by the framing of his mustache and beard.

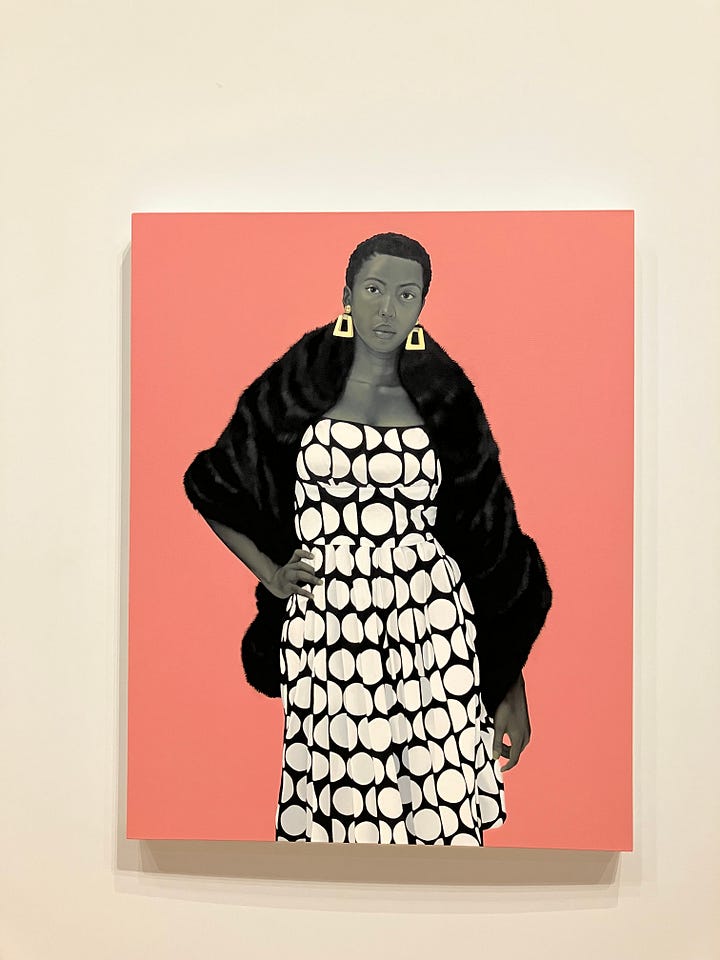

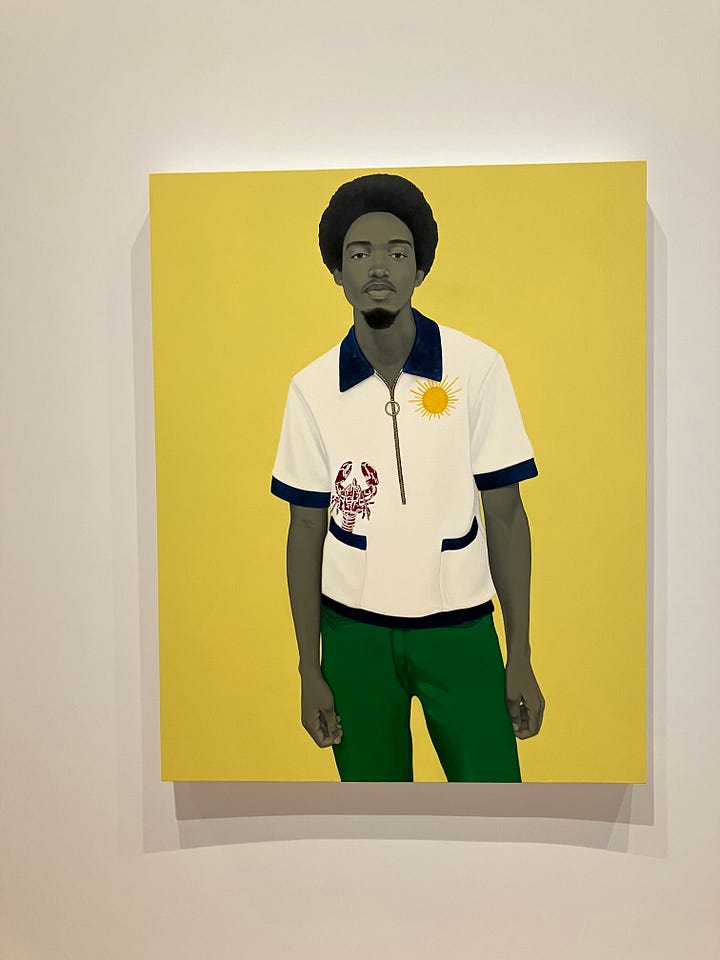

I bring this series up now because I recently saw the Amy Sherald exhibit, on display at New York City’s Whitney Museum of Art through August 10th. Sherald is best known for her commissioned portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama, but that exquisite painting is just one of many in her hallmark style of flattened representations of people standing against blank solid-colored backgrounds. Sherald, a Black woman herself, almost exclusively paints Black people, especially women. She cites a broad art historical lineage through Edward Hopper and American realist painters, but to my eye her work is closer to the formal experiments of Alex Katz than the more social or psychological tradition. Like my father’s works, few of Sherald’s subjects are named. Instead, her titles usually come from quotations and phrases.

The Obama portrait is miraculous, and in person it has a sort of elegant seriousness that I imagine was exactly what both artist and sitter intended. Obama looks monumental, like statuary, a symmetrical face atop a solid pyramidal foundation, with its own geometry. Like with my father’s Blue Sky paintings, the light blue background provides both contrast and universality. The blues of nature evoke constants against human variety and change.

Sherald’s almost full-length portraits are bolder compositions and more finished than my father’s informal works. Her background colors vary and her sitters’ outfits, like Obama’s dress, command attention. But, despite Sherald’s amazing proficiency, these are not exactly psychological portraits either. The faces are mostly expressionless, and very still. The woman in the swimming cap (below) looks almost like her face was cut out and pasted in. Indeed, the figures look almost like paper dolls. And I think this was probably intentional. I think Sherald wants to hold something back, to protect her sitters’ privacy. Above all, these beautiful portraits convey respect, which also keeps them at a bit of distance.

In contrast, most canonical portraits push personality forward, even to the point of quirkiness. I recently finished reading Jean Strouse’s Family Romance (2025), a remarkable account of John Singer Sargent’s twelve portraits of the Wertheimers, a family of London-based art dealers. For Sargent, the interpersonal dynamics among one large family that he personally knew well was irresistible. Like some long-running dramatic series, he painted them over a decade, while the children grew up, married, and left home. He was after idiosyncrasies within a constrained form. In her book, Strouse quotes Sargent’s bon mot that “a portrait is a painting with a little something wrong about the mouth.” Perhaps in painted faces it’s the mouth that holds the most personality, not the eyes. The mouth, mobile in life but fixed on a canvas in some awkward shape, is too hard to pin down.

“A portrait is a painting with a little something wrong about the mouth.” —John Singer Sargent, quoted in Jean Strouse’s Family Romance.

Despite Sargent’s claim, I don’t see anything awkward about the mouths in Sherald’s portraits or my father’s Blue Sky paintings. It’s the relationships among the whole that matter most, in the compositions or in a family. For the paintings, it’s the weighing of parts— eyes, nose, mouth, but also brows, chin, shoulders… and gesture for the few who have gestures. The humanity in the Human Comedy is proportional.

I haven’t hung any of these Blue Sky paintings on my walls at home, or any other portraits for that matter. They may ask for too much engagement, like living with another person’s presence. Even the Sherald exhibit was almost too much— whereas one of her paintings at a time is beguiling, a room full of people staring back at you is uncomfortable. Sargent’s Wertheimer family was intended to be displayed together at the Tate Britain, but they are rarely all united. Maybe that too is overwhelming. Last year, at an exhibition of Sargent and Fashion2 in Boston I became actually nauseous and dizzy from the crowds and the overstimulating details spilling from every wall. I sat down on a bench outside, breathing deeply and blaming myself. I had been looking forward to that exhibit!

Like eyes, noses, and mouths, the pieces of this essay connect categorically (portraits, American) but hang together loosely. Spanning widely different artists, centuries, and sitters, these works have few obvious commonalities, besides decontextualizing their subjects by placing them in empty rooms. Yet all engage with similarity and difference, theme and variation, in their own unique ways. How do you see these sitters, through these artists’ eyes? How do they seem to see themselves? Let me know in the comments!

Thank you, as always, for reading! I love the opportunity to connect dots for myself and others, to figure out what I think. I appreciate the company.

A related post about my father and portraiture, which discusses some sketches and a portrait of me:

Daddy-O

Six months into this newsletter, what else can I tell you about my father? I’ve explained about his birthday. I’ve told you the Cracker Jack story. You should also know that he liked to walk arm in arm with his daughters, he liked to drink sherry on the porch of his Victorian home, he loved beef bourguignon.

The 14 subjects I’ve counted include a Black football player, a Black woman in a yellow sweater, a white army veteran in a camouflage jacket, a white baseball player, a white basketball player, a white man pointing his finger horizontally, a white man wearing headphones, a bearded white man in a red checkered vest, a white woman in a red snowsuit, a Black man in a Jamaican hat, a white man sitting on a rooftop, a white male runner, a white male hippie, an older white woman in a lavender coat. Some of the blue skies include clouds; many are just flat blue.

Sargent is still having quite a moment. Another exhibit, on Sargent and Paris, is now on at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until August 3.

"Perhaps in painted faces it’s the mouth that holds the most personality, not the eyes." Wow, I think that may be true! While I admire them greatly, there is an force to these portraits that would overwhelm my home if they hung on my walls. Maybe it is the combination of the flat plane and the intensity of their gazes. Wonderful paintings!

I also like theportait of the man in the red-checkered vest. The face is so well done, so expressive. If you changed the clothes, it could also be an early renaissance Italian portrait.