Daddy-O

For Father's Day, a character sketch.

Six months into this newsletter, what else can I tell you about my father? I’ve explained about his birthday. I’ve told you the Cracker Jack story. You should also know that he liked to walk arm in arm with his daughters, he liked to drink sherry on the porch of his Victorian home, he loved beef bourguignon. (“Did you find the pearl onions?” he’d ask my husband, who often cooked his birthday dinner.) He was squeamish about blood. I’m less worried about the accuracy of my memory (a lost cause) than I am about the completeness of my research. Have I collected all the remaining details? No.

Earle was a collector all his life, with a highly-developed eye. Having an “eye,” or innate visual good taste, was a genetic inheritance I missed out on, though my sisters got it in abundance. Earle rolled his own eyes about museum-goers who said they “knew what they liked,” but he was equally passionate about his instinctive preferences—and his tastes were eclectic. He liked the interior decor of the mid-nineteenth century American Empire, the Baroque portraiture of Rembrandt, Holbein, and Velazquez, and the operas and symphonies of Mozart. But he also admired early American folk art. He hated both the flowery excesses of Art Nouveau and the dour Danish Modern interiors he grew up with. When mid-century modern furniture came back into style at the turn of the twenty-first century he was confused: that was the bourgeois, determinedly-unstylish style of his parents and he instinctively recoiled. Having terrible taste was a head-shaking shame, but also a moral failing. Once he described my sofa in San Francisco as “tomato red” and I understood that he was mad at me. My sofa, and I, had disappointed him.

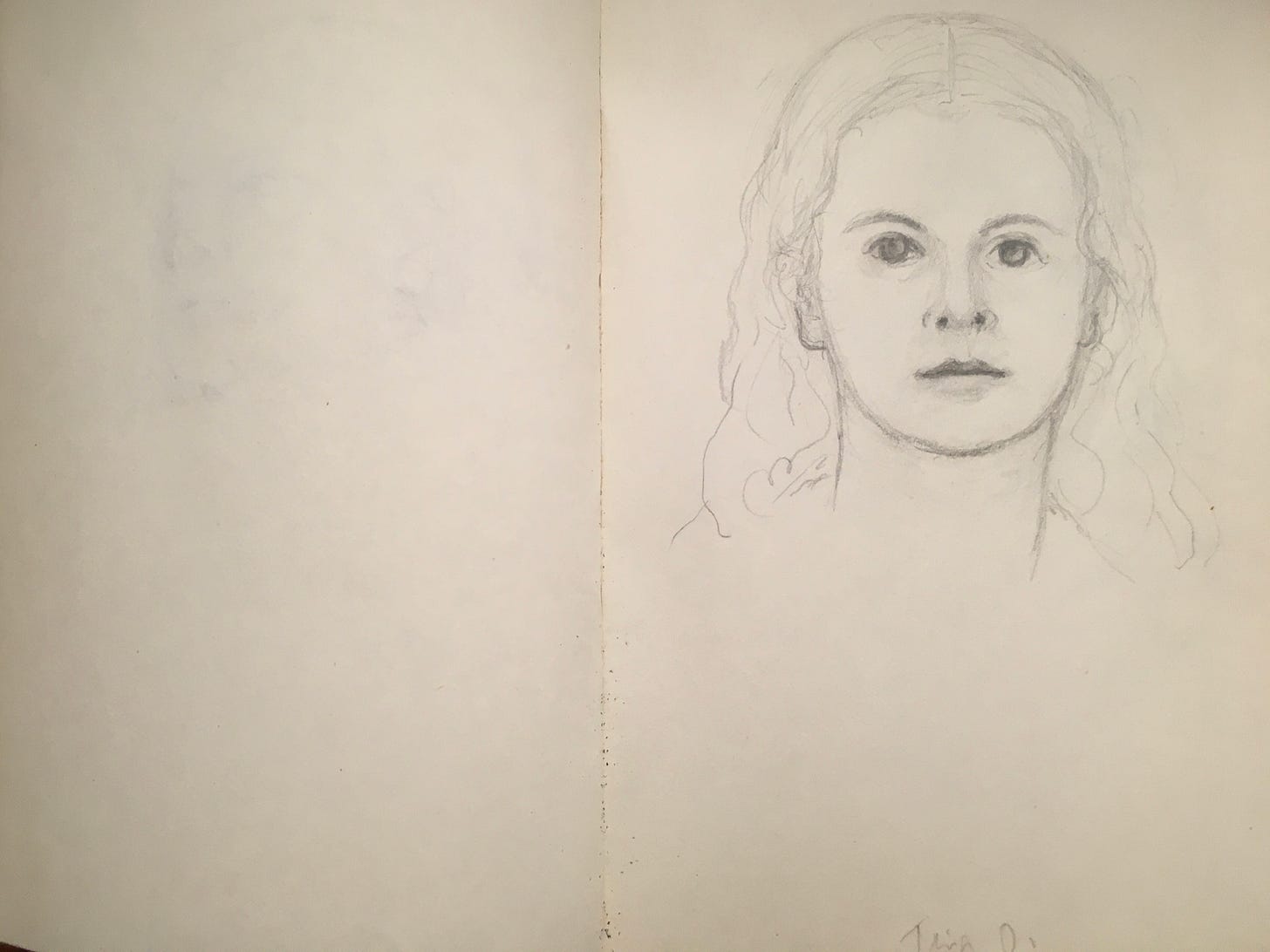

Earle painted during his custodial weekends with us, but mostly I remember him sketching, filling black bound books with pencil drawings of us, of people he had seen on the street or the subway. As a child, it was normal to pose, to be still for him: a little boring sometimes but not burdensome. The sketches he made of us capture something life-like in each child. He made a rough painting of one sister that was full of motion. He sold that one, which puzzled me at the time. Sketching us felt personal. My father’s portraits felt like real people to me, and family members. How could he sell any of them? And he rarely did.

In the only painting he ever made of me, I’m a blank blond-haired child, expressionless. I don’t remember sitting for it. It looks more like my youngest sister in our family portrait than me, like the princess in Las Meninas, like the central child in Seurat’s Sunday at the Grande Jatte, which my father grew up seeing at the Art Institute of Chicago, like Maisie in Henry James’s What Maisie Knew…. I could go on. This girl is generic. Except… look at those eyes, darting to her right in her utterly still face. And those dabs of red accent (like the tomato of my sofa, maybe?). How did he see me?

How did I see him? Here are some more details:

After my father left my mother in 1970 he paid her no alimony and dragged his feet about childcare payments until she had to sue him for them. I know where the court papers are but have been afraid to read them.

In the meantime, he bought a summer house in Greenport, Long Island, admitting to his father in 1972 that he had stopped working for most of that year to paint. My grandfather scrupulously recorded all the money he sent his son from 1974-76: it totaled over thirteen thousand dollars.

These are facts, but the evidence is hardly unbiased; I am the one presenting it. I loved him but I knew him well; I loved him and I knew him well.

There was no question of joint custody back then; we stayed with our mother. But we spent every other weekend with our father as well as some vacations. And we had a lot of fun together. My dad made crepes for us Sunday mornings and drove us around in his vintage cars. We went to diners and ate caramel apples on trips to the country, endlessly browsing through antique stores and yard sales, sifting through piles of old postcards and costume jewelry. After he sold the Greenport house we haunted open houses for country homes upstate, my sisters and I squabbling over who (hypothetically) would get which room. When my father finally bought one on the Hudson River in the mid-1980s we’d spend Saturday nights at church auctions, using paper plates to bid on antique furniture to go with it. We listened to Cat Stevens and watched James Bond movies, or Alfred Hitchcock. At Christmas he decorated all the plants in his house with sparkly white lights and signed our presents from “Daddy-O.”1

This excerpt from my memoir about my father lands early in the manuscript. Here I paired it as a character sketch with his visual own portraits of us. His sketches are similarly informal, a little hasty, unfinished. Even his painted portrait of me is a bit rough, with a mere outline of a chair, body, and background. I too try to start with physical evidence, adding some bits of his voice and taste. I chose that first photograph of my father on purpose too— because of its fish-bowl view, its distortions. The house seems too large, though it was actually that central in my father’s life.2

It is obvious that I am already interpreting evidence in this piece, telling a story, not showing it in scenes with action. What do I want to figure out—and why does it matter? I started this book project wanting to know how my grandfather’s success in commercial design impacted my father’s career in fine art. But that might not matter to my readers. More universally, I wanted to know whether art and family had to be in conflict. But I wanted to avoid conflict too. And a memoir needs conflict.

I loved him but I knew him well; I loved him and I knew him well.

To know and love my father was to see his childishness and selfishness alongside his charm, both laid out in plain view. Like everyone else, he was a mixed bag of flaws and gifts. The only reason for me to believe he was exempt from this human condition was that he was my father.

Please like, share, and comment if you enjoyed this post! I’d be interested in hearing from you about other father-types on this Father’s Day…. Father’s and Mother’s Days in the United States were a relatively recent commercial invention that we didn’t celebrate in my family until I was an adult. I still resist it as a gift-giving obligation, but it works as an opportunity to recognize and credit the roles special people play in our lives. (This year in the U.S. it also falls on Bloomsday!)

I use Daddy-O as the title of the whole memoir as well as this piece. My father used it as a signature and it evokes the 1950s so well.

Someday I will write a whole post about my father’s house upstate. He loved it so!

You write: “Having an “eye,” or innate visual good taste, was a genetic inheritance …”

I once thought this was true, but I don’t believe it anymore or at least I don’t think it’s complete. I think this is a skill that can be learned. I, born with the “gift” of an analytical mind, have learned to approach seeing in an analytical way—and a way I couldn’t do when I was young. I’m not claiming that I have a highly skilled eye, just that I’ve been able to develop some skills, and I now believe that seeing is a learnable skill.

Maybe “having an eye” presents as if it were an unobtainable gift when you encounter artists who not verbal, not analytical, and thus not “gifted” with the ability to explain their taste and what they’re seeing. When they exercise their judgement, it seems magic, because they don’t explain it in non-magical terms.

Your dad did have an amazing eye though :-) I’m thinking of him today. This was a beautiful piece.

I like the portrait of you very much! He caught something of you from so little. I want much more about how you feel about what you’ve learned about his walking away from responsibility, of course. And I recently unzipped my parents divorce documents, in an act of bravery. (Check out “Riptide.”) I look forward to reading and learning more.