Elsewhere I wrote about an institutional research trip—with appointments and applications and procedures. The kind where you check your coat and bag and bring only a pencil and laptop into the room with you. This week I’ll share some more humble research sources.

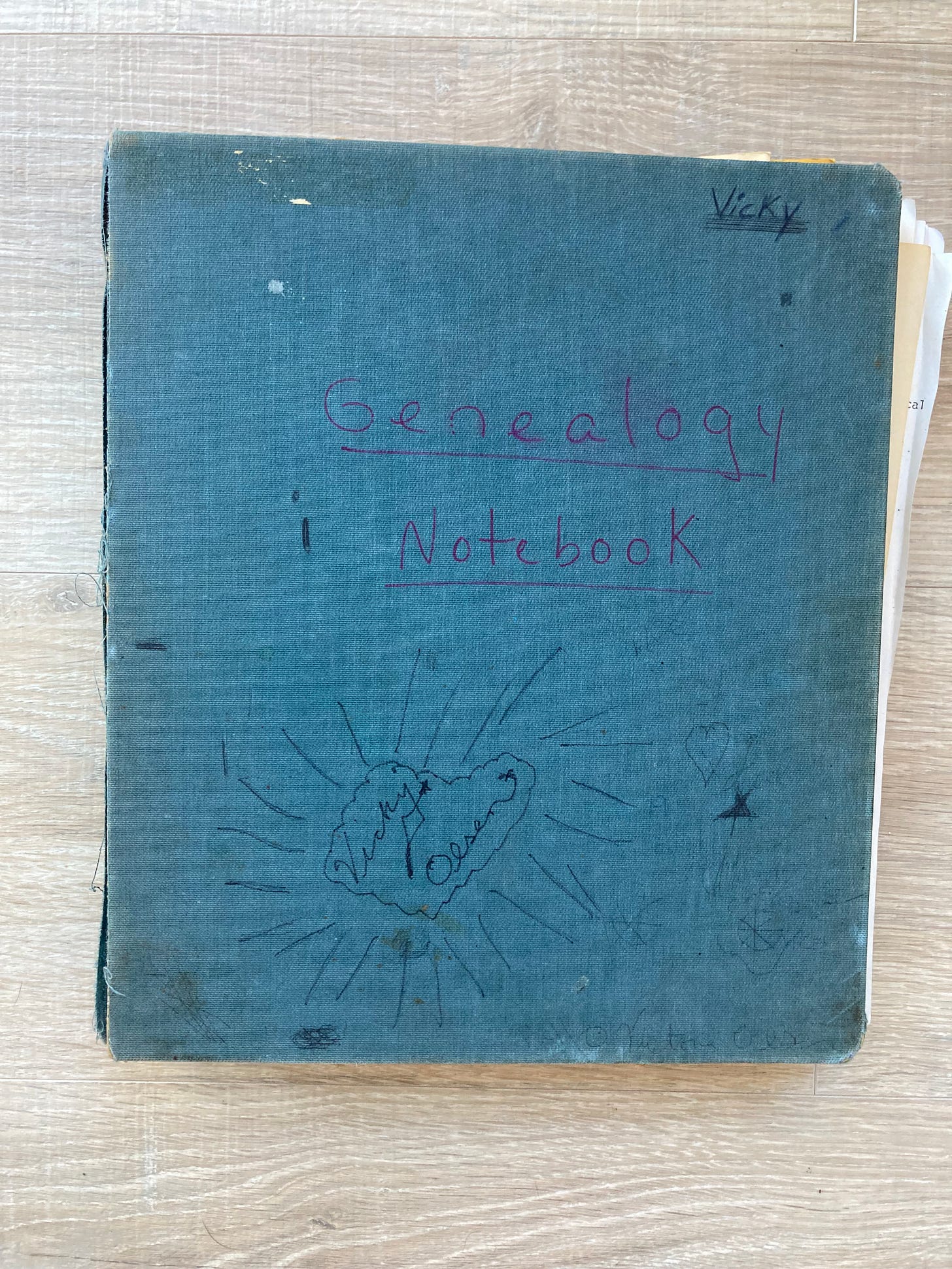

In a sense, my research for my family memoir began in 1977, when Roots aired on television. I was thirteen years old and wrote to my two surviving grandparents for their family histories. They both indulged me. And those letters to my grandfather Andrew were my first research gap: for years I couldn’t find them. Then last week my mother handed me a tattered denim binder labeled Genealogy Notebook. And there they were, just as I remembered them: Andrew’s shaky handwriting in ALL CAPITALS filling in the lines between my carefully scripted questions on a folded blue-ruled page. As a budding genealogist, I wanted to know the facts: names, dates, and places. I was already building an archive, already in love with documents, artifacts, and evidence.

During my genealogical mania I sat in my maternal grandmother’s den and sorted through piles of old family tintypes kept in the leather-bound steamer trunk she used as a coffee table. She identified names and relationships and I labeled them all with adhesive tape on the back, oblivious to any sort of archival practice. It was well before the internet era of digitized databases, so I filled out forms in triplicate, pressing down hard with a ballpoint pen, and mailed them to the National Archives for the Civil War records of her grandfathers and their brothers. I kept the photostats I received in the mail—curling in on themselves like scrolls of papyrus—in manila folders. These too reappeared in the Genealogy Notebook.

Those encounters with my grandparents produced stories I could never document. For example, my great-aunt told me that my father’s grandfather was orphaned in the Chicago fire of 1871. The boy and his sister were then adopted by a farmer who changed their last name. That grandfather, Henry Anderson, was born Galvin. It was an early lesson in the detours and red herrings of the research process. A search for Henry Anderson’s birth records would have gotten me nowhere (I never found the right Henry Galvin either. There were too many. And this story foreshadowed another: my own father had two birth certificates. One for his birth on December 26, 1926 as Sandford Earle Olsen and another in 1929 when his parents changed his name to Earle Stanton. Why, I wondered? He was already three years old. My father claimed that they didn’t want him to be called Sandy.)

Those early research skills stood me in good stead when I went looking for my father’s and grandfather’s names in libraries and online archives. I have paged through digitized records, searching for details about their lives and work and searched paper collections by hand. One winter day I walked a mile through slushy snow and single-digit temperatures to the Chicago History Museum to find no mention of my grandfather’s commercial design work in the annual Art Directors of Chicago Club exhibitions from the 1940s or 1950s. He was not a joiner, I concluded. I looked for reviews of my father’s paintings in New York City art journals. I combed oral histories of artists from his alma mater, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, to see if anyone referred to him. There was almost nothing. Sometimes I wondered if they left no mark on history apart from what was left in the boxes in my basement. It was unsettling.

But then I’d find something small and special: a reproduction of one of my father’s paintings among the Smithsonian papers of Thomas Hess, editor of ArtNews. Or my father’s name under O in two address books: one from a New York City gallerist and one from a teacher at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Earle Olsen—both with an e. These became the tiny stitches, hardly noticeable by themselves, that make up the whole portrait of a life and give credence to an interpretation.

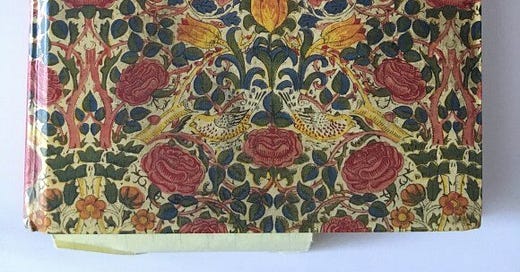

Finding these address books sent me back to my father’s address book, which leaned against the few other books and agendas I’d saved from his house when we disassembled it. It was a familiar book, covered in a paisley William Morris print, perhaps bought at some museum gift shop. It was battered from long use and stuck with scraps of paper carrying long forgotten phone numbers. When my father passed away I thought I knew everyone I needed to contact; it hadn’t occurred to me to call any of the unfamiliar names in that book. Later, though, I would find two of his oldest friends in there, fellow alumni of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago: Winston Hough and Robert Andrew Parker. I hadn’t known he was still in touch with them. Eventually I was able to speak to both of them about their memories of my father in the 1940s and 1950s.

In my memoir, this excerpt opens an early chapter and I think it does a good job of introducing me and my process. It went on after my father’s name change to talk more about the patronymic name Ol-sen for a family with no sons. (Maybe I’ll include that in another post!) An earlier draft also had a lot more background information about my grandparents’ families, but I cut what one of my readers called “the begats.” Overall, I think the bigger point is how and where to find your own family— perhaps where you least expect them.

In other words, you don’t know where the smallest detail will lead you. A stack of cancelled checks documented my parents’ daily lives in the 1970s, as well or better than any diary. My father’s day planner from 1969 pointed to his professional appointments with artists and galleries when he worked at Kulicke Frames. These sources gave me a slew of new names to research. From an inscription written in a National Gallery of London catalogue I traced a path to Godinton House in England, where my father stayed in 1954 and which I visited this fall. I will write about that trip and these characters in other posts, but here is my takeaway: mine the material right in front of you, no matter how humble. I looked for my father in all the usual biographical haunts—newspapers, letter collections, oral histories— and found much less than I expected. But smaller traces were everywhere.

As I’ve said, at some point I’ll be putting these exercises behind a paywall at some point and rolling out other perks for paying subscribers. Until then, feel free to use the comments to share your own research stories or tips—or try out this exercise. I respond to all feedback! And please share or like or restack this post— engagement is how writers find readers. Many thanks for your time and attention!

Exercise: Brainstorm a list of the most quotidian sources for your project. Maybe you have some already that you haven’t mined enough (like an address book) or maybe you can access some in public records— like telephone directories for places you’ve lived or historic local newspapers for locations that are important for your story. I’ve found the advertisements around marriage announcements, for example, to be especially useful for getting a sense of the cultural mood of that moment. Some digital resources require subscriptions but I am a great believer in the free trial membership if you can organize as many queries as possible into a short period, then make a note to cancel before you are charged.

Resources: One final note on address books: while drafting this piece a few weeks ago, I stumbled on this post by

that shows exactly how to mine an address book for emotional content as well as information: she writes,“my own past addresses are portals to entire worlds of feeling and experience, and the numbers and words make my heart beat faster.”

Genealogical newsletters I’ve enjoyed consistently include

’s Writing Family Histories and . Browse and enjoy!

Speaking of humble sources--that denim-blue notebook is a tantalizing hint about you, the biographer...

That denim binder kills! Because I had the same and it was everywhere in the seventies. When I read this I thought more about your name and how to changed it at my from my pov from Vicky to Victoria to write this, but the binder shows it! Also, wondering about your feelings about the records you kept as a born genealogist and the ones your father kept as someone who resisted being recounted as himself. Was it like being at odds or in league? How did it lead to this moment?