“(Why did people back then always pose for pictures standing by a car?)” —Sigrid Nunez, The Friend

Among the family albums and papers I inherited was a small white envelope labeled in my grandfather’s hand in all capital letters: EARLY CADILLACS. Inside were a handful of photographs of several long sedans from various eras. They were parked on residential blocks in Chicago, and documented from several angles. These images had no people in them, but others in the archive included family members sitting on running boards of classic cars from the 1920s and two where a grinning Andrew (my grandfather) and then a glammed-up Elsie (my grandmother) sit inside an old soft-topped Model T-style vehicle, posing. Perhaps these were taken in 1921, when they married and set up their own home. If so, they are as proud of this new car as of any new baby.

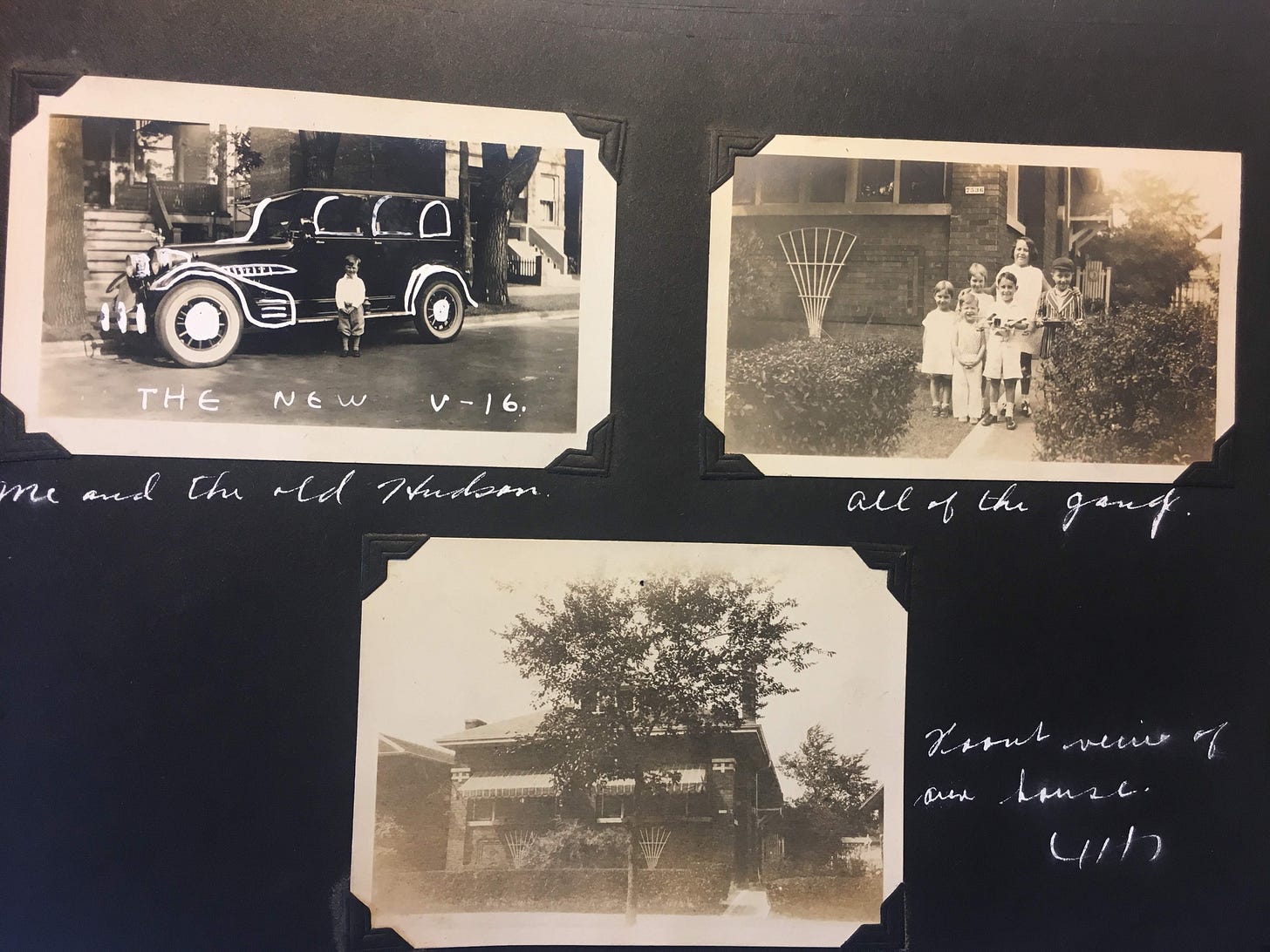

Altogether, my family photo collection includes some twenty loose images that feature cars in some prominent way. There are even more glued into the family photo albums. Inscriptions like “Earle and our Ford” and “Me with the old Hudson” turn the cars themselves into family members alongside my father Earle and his older brother Andrew Jr. Now, those photos curl at the edges, coming loose from their sleeves and falling out of order.

The earliest cars in our archive date to around 1917. At that time Andrew’s parents, an ironworker and a housewife, had settled on the western edge of Chicago and their only son was well launched. The road ahead promised prosperity, which it delivered, even through the Great Depression. Our family cars had the solid shoulders and metal bulk typical of a certain American mid-century bluster and confidence. As design objects, they were associated with the Streamline Moderne industrial design emerging from Chicago during the 1933 World’s Fair, which gave chrome curves to Electrolux vacuum cleaners and sleek lines to boats and trains. Those cars took up a lot of space. They cost a lot of money. My grandfather paid for all those cars by designing advertisements for Chicago companies like Allstate and later packages for Kleenex and Kotex. Paper, packaged as tissues or glued into Andrew’s professional portfolio, was the basis of the family fortunes. For my grandparents and their parents, who had arrived by steamships and railroads from the old countries of Denmark, Germany, and Ireland, cars were objects of status rather than symbols of any American dream of hitting the road; their cars were more about arriving than departing.

In contrast to his parents, who had arrived, my father seemed to be always leaving. After graduating from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (SAIC) in 1951, he escaped to New York City and never looked back. Offhand, I can count about ten addresses for Earle as he moved between apartments, houses, and lofts over the course of six decades in New York. He left home again and again: after he left my mother, most of our weekends with him were spent driving around in a vintage car idly shopping for a house in the country. We scouted Victorian homes in small towns as well as farm houses on acres of land or the occasional colonial brick mansion in need of TLC. We drove and drove, stopping at every flea market, antique store, or yard sale looking for art, collectibles, or interesting old furniture my father would cart back to his New York City lofts.

It wasn’t until I had children of my own that I realized not all kids enjoyed this. As long as we were fed grilled cheese and bacon sandwiches and ice cream along the way, my sisters and I were perfectly happy to spend long days like that, spending our allowance on costume jewelry, yellowing paperbacks, or, later, secondhand clothing. As teenagers, we wore men’s tweed blazers with stiletto heels, silk slips as skirts, and cashmere cardigans littered with moth holes. A car was just another aesthetic object: I didn’t learn to drive until I left New York City for graduate school in my mid-twenties, practicing on the road during a cross-country trip to California.

Growing up, I vividly remember my father’s serial collection of vintage cars: a Jaguar pops up in his letters from the 1960s (he bought two while they were married, my mother told me: “one was a lemon”). Later there was a Bentley, complete with a glass divider between driver and passenger. If we three children got loud and unruly in the back seat my father would press a button and the glass would rise up up up to silence us.1 By the 1980s he had committed to Cadillacs, like his father, and owned a succession of convertibles that he would drive in every town parade after retiring to a small town upstate, waving regally. He was easily recognizable wherever he lived because of those well-loved cars.

Cars brought us together and cars kept us apart. My grandfather eventually left Chicago after his wife died. His address book from his last years in Florida lists some friends (“The Jones,” “The Lutzes”) but many more service providers, from lawn care and barbers to restaurants and camera stores. Inevitably, the address book had a detailed listing for Lloyd’s Buick Cadillac dealership in Daytona Beach, including separate phone numbers for Mr. Deasy, Service; Mr. Hock, Sales; and Mr. Rheinhart, Body and Parts. It seems a lonely life, and that’s how I remember it. When my grandfather died my sisters and I attended neither the memorial in Florida nor the funeral in Chicago. My father inherited Andrew's Cadillac and the photos and other documents I draw on now, moved from basement to attic to basement.

A few years ago I visited the Henry Ford Museum in Dearborn, Michigan with the next generation of my family. My sister had moved to Ann Arbor for a job at the University of Michigan and it was one of our first sightseeing adventures into a part of the country none of us knew. To my surprise, the museum was filled with much more than just cars: it contained the ephemera of American cultural history, from farm equipment to dollhouses. Most of the objects seemed much bigger in three dimensions than I expected, in part because the museum itself was the size of an airplane hangar. There were only a few items—like Rosa Parks’s bus—that any of us specifically wanted to see so mostly we browsed like consumers, wandering the wide aisles like it was a supermarket, gawking. A group of eight, we’d drift apart, run into each other, and go off in pairs to get food or find restrooms. As a whole, the place felt like America’s attic, stuffed to the brim and overflowing with cultural memorabilia of uncertain significance. Like a photo album, it was an effort to freeze the shifting tides of time, to pin them in place for future study or reflection.

Most of the photos in my family album manage that task of preservation, of documenting our status and relationships in a frozen moment, but one stands out as an exception. In this one, the photograph is double-exposed; the car at the center of the image is in motion, its wheels multiplying as if spinning. The shadowy figures of the family overlap as ghostly apparitions from the past: my grandfather Andrew, grandmother Elsie, her youngest sister (my Great-Aunt Marie) as a girl with a bow in her hair, smirking from the driver’s seat. The two men toward the back are strangers. Those wheels, once attached in a Ford-like assembly line, are here coming loose off the page. Someone took this photo. Someone related to me, probably. And someone kept it for some unknown reason, despite its obvious flaws. I can interpret it like a fortune teller: the family will be radically shaken by events to come, and will disperse in different directions. I imagine their migrations as red lines crisscrossing an old AAA atlas, fanning out across the country.

Is this the same car as in the 1921 image I started with, where Andrew smiles from the camera with pride and optimism for the future? It could be. It could have been taken that same day, in front of the same house. The car is famously symbolic of American isolation: we commute separately, plated in armor, instead of investing in public transportation like buses and trains, where we would interact with each other. But my family photos show a sort of bonding around the cars too— as different configurations of family members stand before them, including the invisible photographer. For a family of recent immigrants, cars were worthy of multiple reproductions in our archive. These bulky metal objects would anchor us in place, connect us to each other, and drive us apart.

This essay is not actually an excerpt from my memoir, but an outtake. It didn’t fit anywhere and I thought it could stand alone, somewhere else. It’s an attempt at braiding together social and personal histories through a constrained data set— just the photos of cars in my family albums. The automobile is a lucky choice because it so easily symbolic in American culture. From the spinning wheels of the photo to my title “In Motion” to that final verb “drive,” having a central metaphor to hang your piece on is hugely helpful. In this case, it means that I can create coherence and continuity even out of motion and change over time. I just need to keep coming back to cars-as-objects in my family history and the related themes of diaspora and migration.

There are problems though. You can see why I had trouble fitting this in anywhere. It’s actually too self-contained. Some of the middle paragraphs swing a bit too awkwardly from personal to historical, without smooth transitions. The photograph I end the essay with would actually be a better beginning. It is more visually memorable and suggests emotional content. But I felt I had to introduce the family first….and hold the better photograph (the failure!) as a punch line, so to speak.

These are normal writerly choices and trade offs. We’re all used to them but I hope it’s valuable to air an example like this. I sent this piece to some personal essay venues and never got anywhere— for perhaps the same reasons it didn’t belong in my memoir. It is too removed from my own experience– or even my father’s. In fact, one of my last revisions was to change the final sentences from third person to first person (“their” to “our”) to make it more personal. In a sense, the essay shows me spinning my wheels, like the final photo. [See how valuable my metaphor is!]

I struggled too with how much to include about the history of cars in American culture. Much of it seemed obvious to me, but then that’s often where we misstep as writers— in assuming things that are obvious to ourselves are obvious to everyone…. I edited out a few general statements and the example of my father’s contemporary Robert Indiana’s references to Route 66. Overall, I think in this piece I do a pretty good job of integrating research without letting it pile up into deep drifts. I don’t detour too far from my family for too long. [There! Not all my self-critiques are critical.]

What do you think? How do you manage integrating background research into your memoir writing?

I end these weekly posts with an exercise for those of you working on memoir yourselves. Eventually these exercises will be behind a paywall but for now they are available to everyone. You can even post your version into the comments field for feedback— or just for sharing. Your choice!

Exercise: Identify a pattern in your family archive, visual or otherwise. What themes, objects, or even vocabulary come up again and again? I use the family cars as my example but maybe your history includes a word or phrase instead. Describe one such dominating pattern and then interpret what it might mean— for the culture and society of its time and place or for your particular family. Try balancing both elements (cultural context and personal story) in one essay and see how that feels. I’d be interested to hear about it!

Resources: Courtney Maum, who runs a valuable writerly Substack called Before and After the Book Deal, recently published a post about a related technique for fiction that she calls zoom in/zoom out. She talks about this in cinematic terms— as expanding a lens to include a big picture for context before returning to plot and character. It applies equally well to research in nonfiction though.

Is this a metaphor for your relationship with your father? a reader-friend asked me. Yes, though I hadn’t noticed it as such. That is a benefit of sharing your work!

This is the spiciest one! Love it. Those big showy cars say so much. My father bought a jaguar when he launched his company because he wanted people to look at him.

I like that this installment, again, has the phrase “you can see....” it’s such a friendly way to bring us into the workshop with you.