You all know I’m a Victorianist, right? By name and training. I’m often not sure what I’ve said to whom, what’s obvious and what’s not. It’s sometimes hard to know who I’m talking to here. There are readers I know “in real life” and readers I know only online. And readers I don’t know at all. I’ve been on Substack for over a year and I’ve mostly written about art and memoir, but this post reverts to an earlier Victoria. Indulge me.

Last year I began co-writing a mystery novel with a dear friend, excellent writer, and fellow Victorianist, Christina Boufis. She and I met thirty years ago at a camp-like summer institute in Santa Cruz called The Dickens Project. We both have Ph.D.s in Victorian literature, but didn’t end up as academics.1 This collaboration was her idea. She has published mysteries before and wanted to try a historical novel together.2 “We should use those degrees!” she said.3

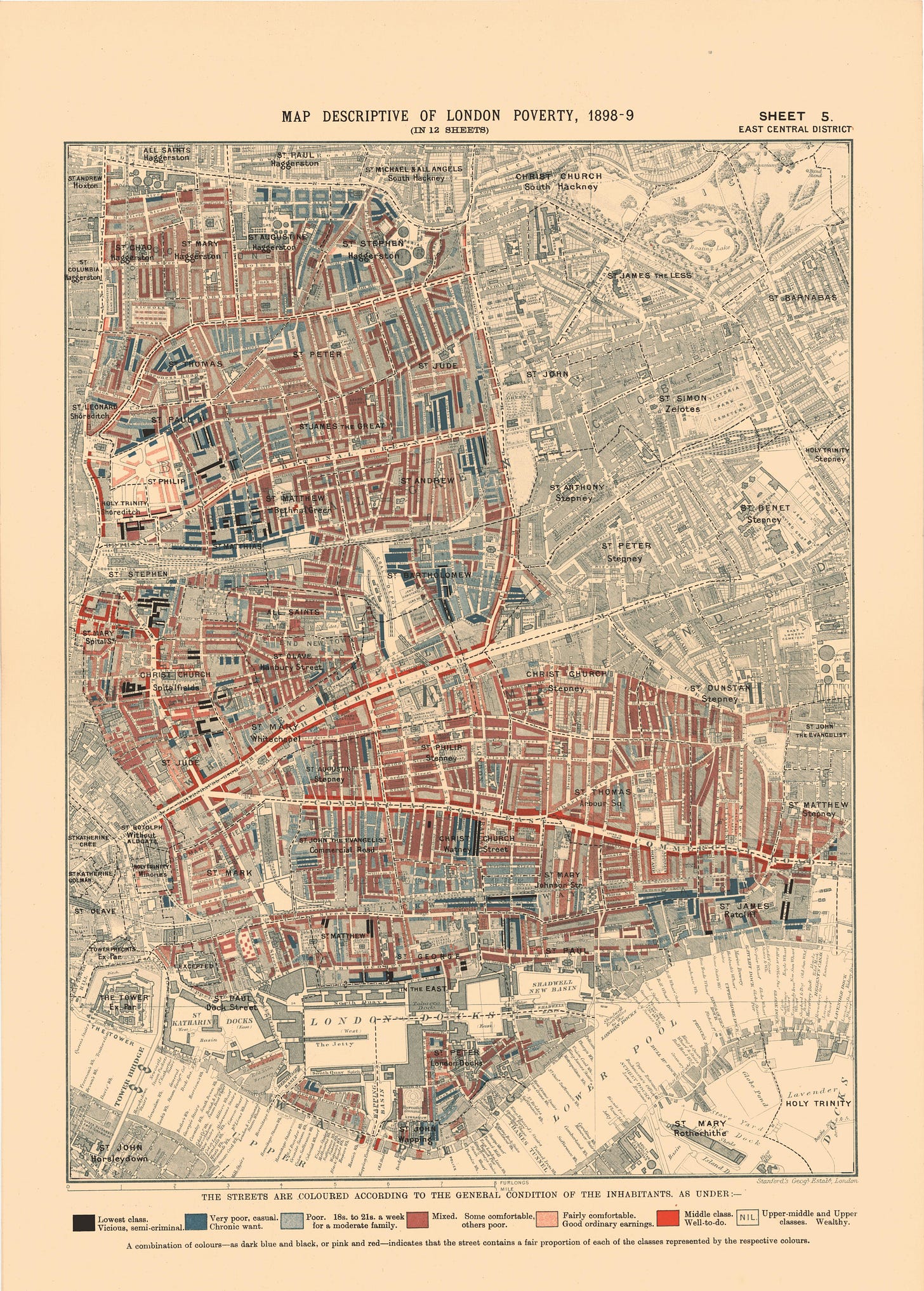

For this new project, Christina and I wanted to combine two iconic Victorian crime tales: the historical Jack the Ripper murders in 1888 and the fictional Dracula, first published by Bram Stoker in 1894. We wanted our novel to give voice to the working-class women who were killed in Whitechapel, including sections from their points of view. For those details we drew on Hallie Rubenhold’s impressively researched account of their lives in The Five. We also read up on Victorian crime and pre-Stoker vampire stories like Carmilla and Varney the Vampire. Last year I re-read Dracula on a flight from Paris to Boston, in seven and a half straight hours. It spanned take-off and descent, from old to new world, traveling East to West, like Dracula himself. I loved it, despite the problematic parts. It’s a great page-turner.

As we prepare to publish our mash-up, here are a few thoughts for those who haven’t read the original source:

The form of Dracula was, and is still, fresh and astonishing. Stoker tells the story through several points of view via an assemblage of documents, including typed diaries, handwritten letters, newspaper clippings, medical notes dictated into a phonograph, and telegrams. He is obsessed with new technologies and social change: the dictaphone, the typewriter, blood transfusions, criminology, psychiatry. This gives the sensational narrative the reality effect of “simple fact,” as Stoker calls it in the introduction. It’s a very clever conceit, and well executed. The “ancient evil” is contrasted with the hub of modernity. Our novel alludes to that structure by incorporating excerpts from actual Victorian newspapers of the time, which were fun to find.

The original Count Dracula was not a sexy romantic lead. He was an old creepy guy described in obviously xenophobic, anti-semitic terms. He crawled headfirst down castle walls and could turn into a bat, a wolf, a mist, and flickering light showers. He communed with rats. Gross.

Lucy and her three suitors are typecast out of romance novels: the cowboy-ish American, the doctor, the aristocrat. Of course she chooses the lord! But she wants all three of them, musing “Why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many as want her, and save all this trouble? But this is heresy, and I must not say it.” In the popular romance world, “reverse harem” novels are all the rage now.4 The tag line is often “why choose?”, which is a great comeback to the trad romance suitor-plot. Our novel focuses more on Lucy’s friendship with our Mina, whom we call Maude, and their fierce band of vampire-fighting women than with courtship.

“Why can’t they let a girl marry three men, or as many as want her, and save all this trouble? But this is heresy, and I must not say it.”

Dracula seems to be a paradigm of patriarchal heterosexuality: ie. old dude preys on young innocent girls. It’s been read for its anti-immigration fear-mongering and also as a recoil from the “New Woman” of the late nineteenth century, with her more assertive sexuality and professional ambitions. But there’s a definite queer subtext to the story too: as the three male friends vie for Lucy’s hand. Literary critic Eve Sedgwick called this a kind of “homosocial triangular desire,” in which men’s desire for each other is displaced indirectly onto a mediating woman that two men compete for. As Lucy weakens from the vampire’s predation, the three friends all share their blood with her through the new technology of transfusions. The logic of this is to share their virile good health with the fragile young lady, but it doesn’t really make sense since the elderly Van Helsing participates too. These repeated efforts don’t save Lucy (she needs to be sacrificed, perhaps in part for her “heresy”) but it effects a symbolic intermingling of all those bodies. In a wide-ranging essay for Guernica,

explores the biographical basis for a queer reading of another trio: Stoker knew and admired both Walt Whitman and Oscar Wilde. He notes too that Stoker and Wilde may have competed for the same Irish woman, Florence Balcombe, whom Stoker eventually married: “A strange love triangle presides all the same over the novel, though perhaps it is a pentacle: Whitman, Wilde, Stoker, Balcombe, and Dracula.”Bloodsucking may seem erotically charged but the deaths of Dracula’s victims were actually violent. Once turned into vampires, they needed more than a wooden stake through the heart to end them: they were dismembered in a gory fashion reminiscent of the Ripper murders against working-class women. In the end the suitors must mutilate Lucy’s body in order to “save” her from vampirism. The tone is more horror movie than literary classic: “May I cut off the head of dead Miss Lucy?,” Van Helsing asks her fiancé. In our book, Christina and I did lean into the camp sometimes, but we avoided explicit violence. (The Victorian newspapers were as grisly as any contemporary thriller in that regard.)

To end this list on an upbeat, I recommend that anyone who wants to know more about the origins and setting of the original novel check out

s travel essay on Bram Stoker’s Whitby and her exquisite, evocative photos of the Yorkshire coast.

Over the course of last year, Christina and I drafted our novel, called Some Dark Force, on a shared Google doc. We didn’t do much outlining, just adding sections one after another like an extended game of exquisite corpse. By the summer we were able to send it to a wonderful developmental editor, who helped us polish it. And now we’re self publishing it for release this summer. I’m proud of it! And it was FUN (insert joke about low stakes here).

If you’re interested in hearing about our research and production process, you can sign up for a dedicated newsletter on our website. Some upcoming topics will include our cover design process, an essay on a Ripper walking tour I took in London last year, and a review of the latest Nosferatu, by Robert Eggers. My personal Substack will return to its usual programming next time. I appreciate your patience! And your comments and likes!

Once upon a time Christina and I had also collaborated on an essay anthology, called On the Market, about the terrible academic job market we had graduated into. It hasn’t gotten any better.

This wasn’t my very first time writing fiction. In 2011 I self-published a middle-grade novel called Word Blind. Also set in “my” period, it was about two very different sisters dealing with their mother’s death. The idea emerged from research I had done on the Victorian origins of dyslexia, which was called “word blindness.” I enjoyed rethinking that research for a new container.

I had used my Ph.D. to publish a biography of photographer Julia Margaret Cameron twenty years ago, and I taught writing at New York University for many years, but I have never taught Victorian literature, as I had originally planned. Not once!

For examples of this genre, see authors Lily Gold and Annika Martin. Some reverse harem novels go to great lengths to insist that the men are not sexually interested in each other, only in sharing the central woman. Others explore the polyamory more fully.

Wow, how cool! I love hearing your process. So cool to collaborate with a friend. And of course, KRISTEN TATE is the best editor! Sorry for the shouting, I could not help myself. KUDOS on finishing the book!

Super fun read. I knew nothing about the original novel or history and your collaboration sounds amazing