Zurich, 1958

A research find and a summer memory

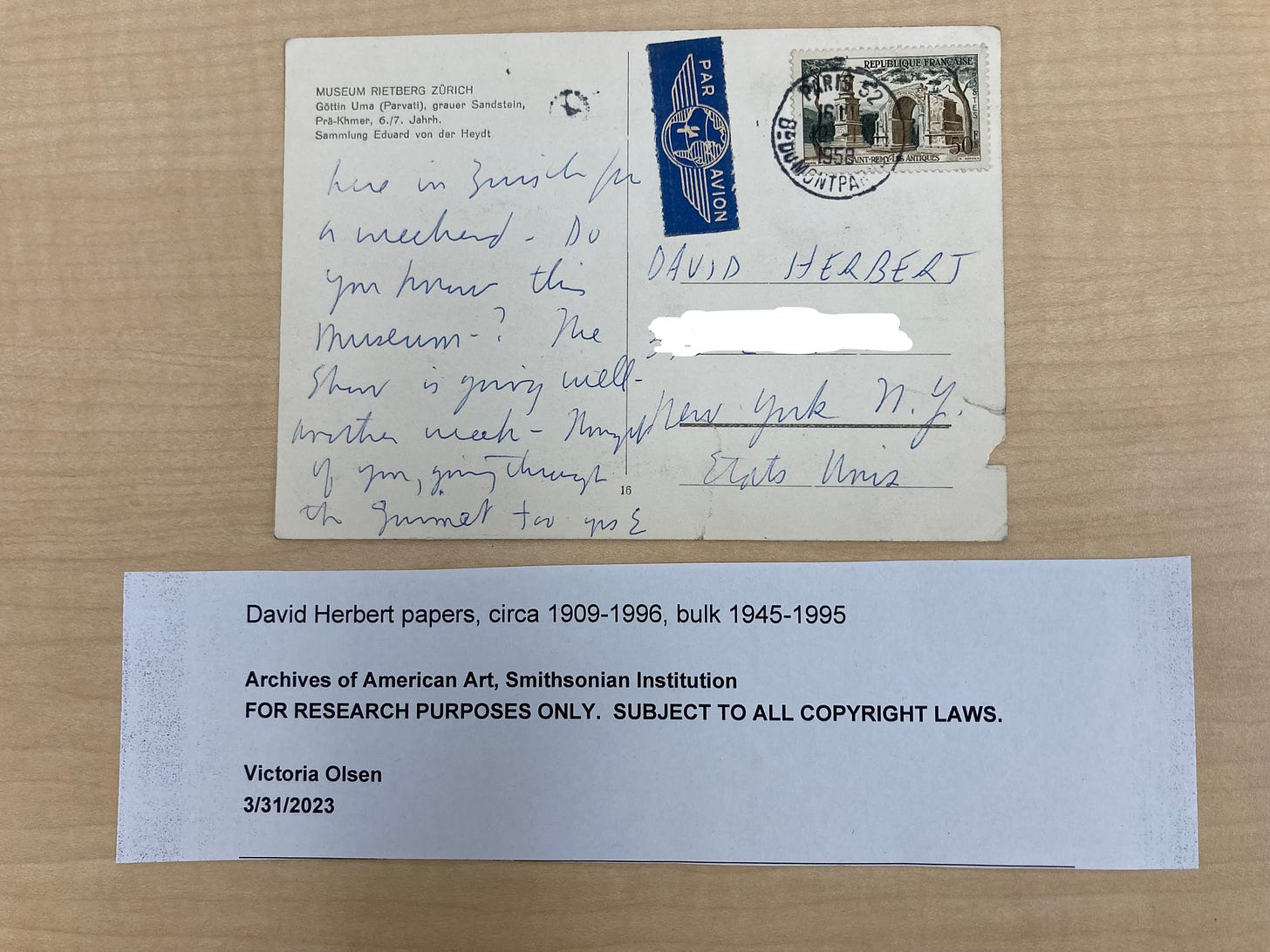

“Turn every page,” Robert Caro says. So when you’re in Washington D.C. at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art flipping through the David Herbert Papers box 2 of 7, “Correspondence: Illegible and Unidentified 1958-92” folder, you might suddenly encounter your father’s handwriting.

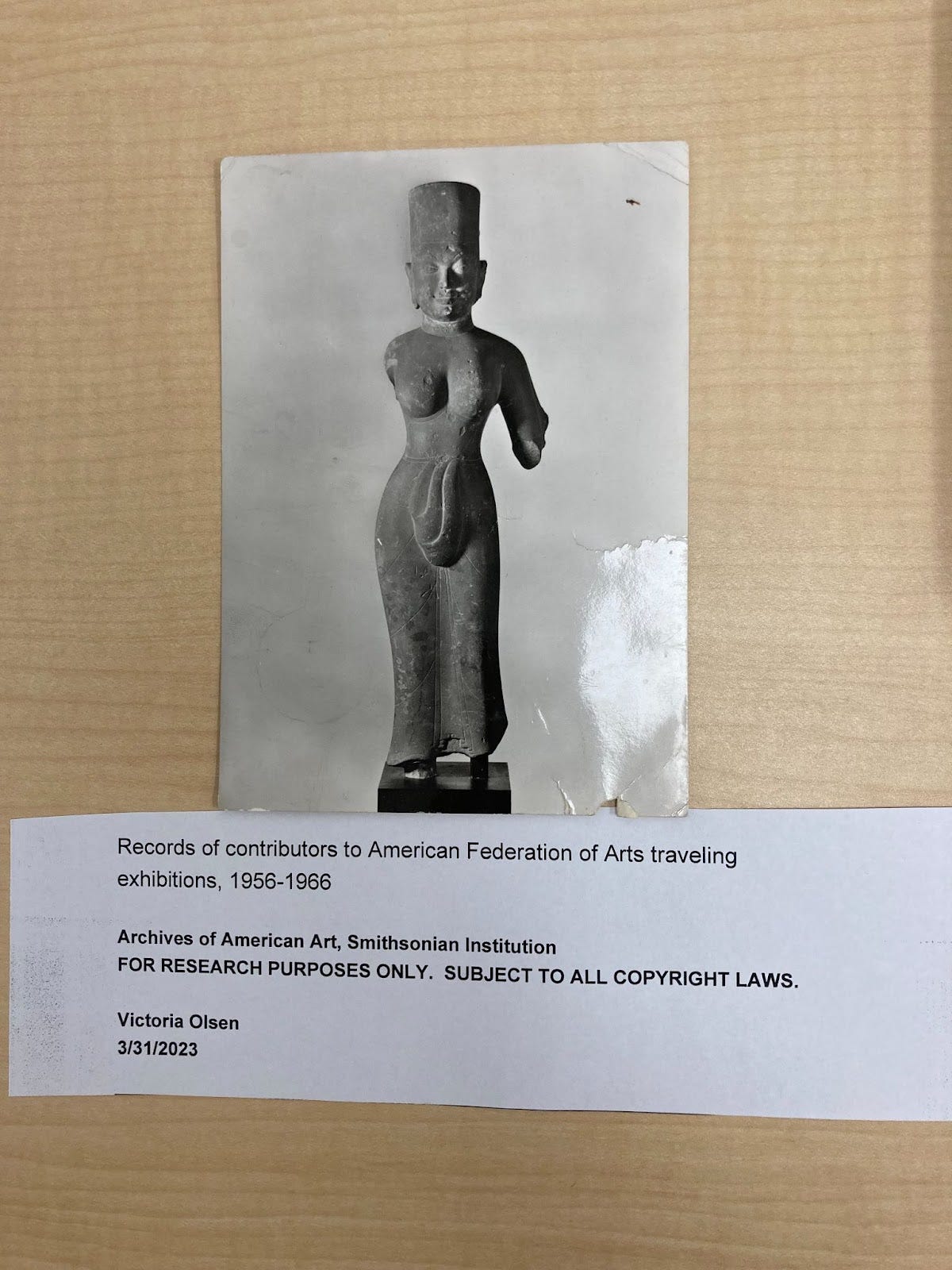

It’s a postcard from Zurich, stamped 1958, and signed only “Yrs, E” so I had to check my instincts with my sisters. “Does this look like Dad to you?” “Absolutely!” “Definitely!!! The handwriting, phrasing, and the E at the end.” There’s also the familiarity of the art on the front. My father admired that kind of elegant antique statuary, like this piece from the Museum Rietberg. He sent and received loads of art postcards, pinning his favorites up next to his easel in his studio.

What is it about this postcard that says “dad” to us? There’s the throwaway tone that starts in the middle of his journey and ends with “thought of you….” Those first few sentences are clipped and simple but they shift into dashes and a fragment at the end. My sisters and I can’t read the noun in the last sentence so we speculated: “Thought of you, going through the [Guimet?] too.” That could be the Guimet Museum in Paris, where this postcard was mailed from, after a weekend in Switzerland. The message feels dashed off.

David Herbert seems to have been another of my father’s gallerist friends from New York City. In 1958 Herbert worked for the Sidney Janis Gallery; later he would open his own. My father appears in his address book1 alongside the enigmatic initials N.F.L. (other names are annotated with the artists they collected). Like many of my father’s friends at the time, Herbert was gay.

Herbert became best known decades later as the supposed source of a cache of newly-discovered Abstract Expressionist works that were sold by the Knoedler Gallery in the 1990s. Over a decade of lawsuits it became clear that they were forged by someone who knew Jaime Andrade, an artist and Knoedler employee who had been in a relationship with Herbert. After Herbert’s death, the art forgers concocted a story that Herbert had had access to private wealthy collectors but kept the purchases secret because some of them were actually his lovers. There was never any proof of this claim, and the story unraveled as the angry buyers of suspect Pollock paintings sued the gallery. It created a crisis of confidence about the art market’s modes of authentication that brought down the long-esteemed Knoedler Gallery.

The “David Herbert Collection” was the fiction at the heart of the scandal, and now it’s the first search result for his name. A Vanity Fair article about the scandal places Herbert in the middle of a gay New York City art world. My father never mentioned any of this; I also didn’t ask.

So what did I learn from this find? My father was in Europe at the end of 1958, while he had a painting in the Whitney Museum’s annual show. If that show was up for another week then this was written in December.

What does this mean? Sending a postcard implies he and Herbert were friends, not professional acquaintances. The “yours” and the “E” imply a relationship that was casual or familiar. The postcard was not a momentous find, but it was satisfying. Every piece of evidence helps. And the process itself reveals how interconnected we all are to each other, and the past to the present. This random piece of paper survived when others didn’t only because David Herbert, someone my father once knew, saved it; after his death someone else thought to preserve seven boxes of his life’s output at the Smithsonian, where someone else cataloged it—there in “unidentified” and “illegible.” It is no longer unidentified: I informed the archivist that Earle Olsen was the author so the postcard should be moved to the folder labeled “Correspondence: O-P, General 1957-92.” That marks another relationship between me and the archive, helping each other: I’ve added one more piece to the jigsaw puzzle of my family memoir.

One summer, when I was in high school, my father took me and my sisters to Switzerland. He had exchanged his midtown loft for a home in Locarno, on the Italian side of the Alps. (Perhaps there was cat-sitting involved? I’m not sure.) We flew to Paris together and took a train there, then lounged around near Lago Maggiore for a few weeks, like locals. I don’t remember seeing much art, though perhaps we stopped at museums. Instead, that trip was about swimming in pebbly creeks and eating late into the night with friendly neighbors. The house was lovely but worn down in ways I hadn’t seen before: Europe was a place where an ordinary home might be hundreds of years old. The tiles were cracked, the rugs threadbare. One of us slept on a mattress on the floor.

For me, it was an early and romantic glimpse of adulthood: adults drank lots of red wine and ate when they felt like it. That summer I was considered old enough to have some adventures of my own in Europe, so one sister and I left together for Vienna, where some of my mother’s family were living, and rejoined my father and youngest sister in Paris a week or two later. I was probably sixteen years old, on the cusp of independence. It was a memorable trip and taught me some basics of managing foreign languages, currencies, and transportation systems. What I may not have realized is that it was probably based on a way of living my father had already experienced as a young man— wandering around Europe after college. He was modeling something for us that he had loved and valued. And it took root in all three of his children.

Did you take any memorable trips as you became an adult? Please share in the comments. And liking, restacking, and sharing helps writers find readers. Thank you to my new subscribers!

So much truth in this sentence, Victoria: “For me, it was an early and romantic glimpse of adulthood: adults drank lots of red wine and ate when they felt like it.” I appreciate its upfrontness.

"Adults drank lots of red wine and ate whenever they felt like it..." That made me smile...sometimes I *still* feel like the ultimate freedom is to be able to eat (or not) whenever you feel like it!