At Sea

Swimming in naval records....

I’m back to paternal genealogy this week, with an emphasis on military records. I’ll end the month with two pieces about my father’s older brother, Andrew Jr.

Both my grandfather and father served in the U.S. Navy for their respective world wars. Neither of them ever went to sea.

In my basement, there’s a water-stained box1, originally for 72 sheets of Handcraft Vellum papers, Deckle Edge, that is labeled in all caps in my grandfather’s careful hand ”SOUVENIRS OF HIGH SCHOOL AND NAVY SERVICE OF ANDREW P. OLSEN.” The box is filled with Andrew’s characteristic thoroughness; if it were stored in an institutional archive, the container list, detailed view, would inventory all of his high school grade reports and his leaves from the U.S. Great Lakes Naval Station, just north of Chicago’s northern suburbs, where he served during World War I.

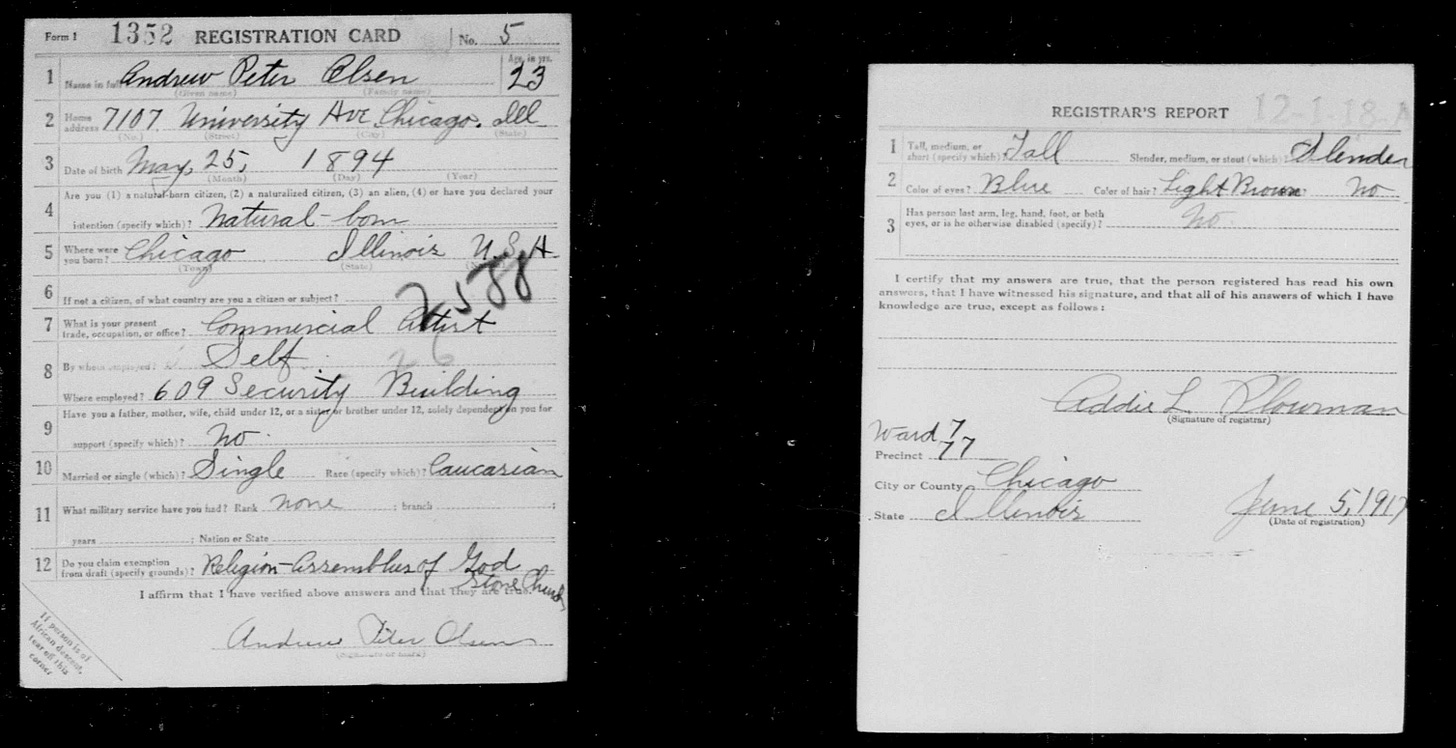

After graduating from a technical high school in Chicago in 1911, Andrew spent several productive years working in the advertising department of Domestic Engineering, the weekly paper of the Plumbing, Heating, and Ventilating Trades. Then, on April 6, 1917 the United States declared war on Germany to enter World War I. The nation’s standing army was small, so on May 18th Congress passed the Selective Service Act requiring all male citizens between the ages of 21 and 45 to register for the draft. When President Woodrow Wilson called this “a new thing in our history” he may have been noting that for the first time draftees would not be allowed to hire a substitute. On June 5th, the first day of national registration, Andrew (aged 23) presented himself to the draft board. I have a copy of his draft registration card. The U.S. National Archives holds 24 million others. In March 1918, Andrew was called up and enlisted in the Navy.

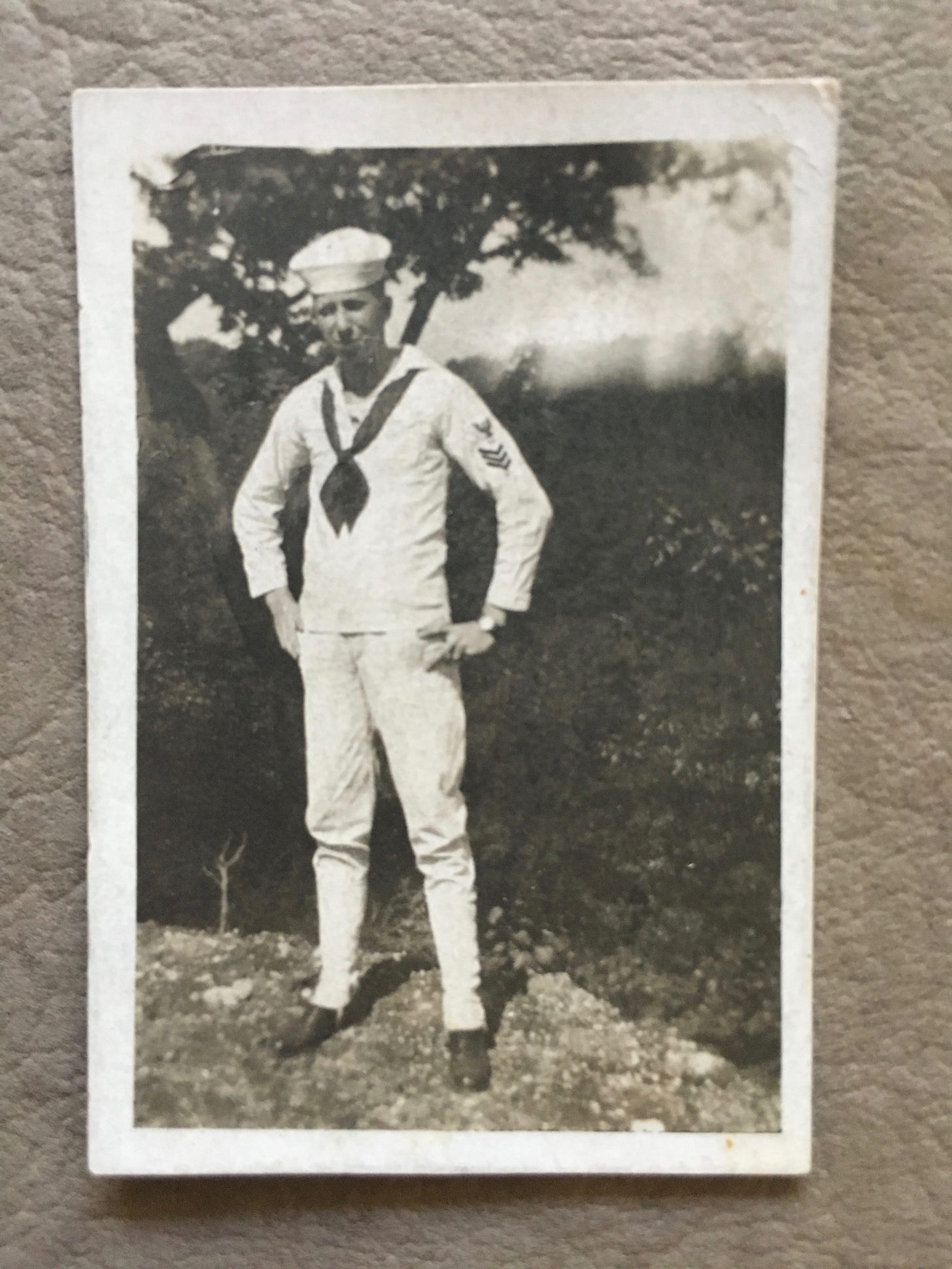

In 2022 I wrote away to National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in D.C. for anything else they might have. In response I received 48 pages of scanned documents about Andrew’s year at the Naval Station. He was fair skinned with blue eyes and light brown hair. He was gangly: six feet tall and 141 pounds. He started out in March as a Landsman (or unskilled) Electrician, but by July his aptitude for art was already noticed and his rating was changed to Painter. In fact, he began a two-month course of preparation to enter the Department of Naval Architecture in Washington, D.C., though that never happened. The war ended on November 11, 1918 and Andrew left active duty on January 30, 1919. He stayed in the Reserves, earning $52 a month, until his honorable discharge on September 30, 1921. The last page of the records has his fingerprint in pink ink.

Andrew returned to his commercial art career in Chicago, married, and had two sons. In September 1941, at age eighteen, the eldest son, Andrew Jr., enrolled in The Citadel and ended up in the U.S. Army Air Force. He died during his service in May 1944 (I’ll tell that story in a cross post for

on Memorial Day). The U.S. government had dropped the age of conscription to eighteen, so in December 1944, my father came of age, graduated high school, and was promptly drafted himself in February 1945. He liked to say that his father wrote a letter to the U.S. Navy requesting that, having lost his eldest son to the war, they keep his remaining son on home duty. I thought this story might be an exaggeration or a family myth, but I duly found the Navy’s response among Andrew’s saved papers. The U.S. Navy Captain politely tells him that “all assignments of personnel are made by the Bureau of Naval Personnel” and cites the official policy that “consideration will be given to the return to, or the retention in, the continental limits of the United States” only for families who lost two or more sons (ie. the Saving Private Ryan scenario).In the family photographs of my father heading off to the Navy the scene looks surprisingly convivial: my father in uniform with his mother, Aunt Anna, and cousin Beverley dressed up and all smiles.2 Is my grandfather present behind the camera? If so, he was outside the happy group of women surrounding his only surviving son.

My father’s experience of military service closely mimicked my grandfather’s twenty-five years earlier, complete with the same carefully preserved leave passes. The Great Lakes Naval Station was completed in 1911 and remains the largest naval training center in the country. During World War I it trained 125,000 sailors; during World War II it trained one million. In 1942 it was the first training site to accept African Americans. By 1945, when my father was there, it was fully integrated. My father was assigned to a radio technician program and described the intense pressure to keep up. “I had to pass every test at the end of each unit or they’d send me overseas,” he’d say. I don’t know how true that was but by the time he was discharged as a Seaman First Class in July 1946 he had graduated from the Naval Training School programs in Pre-Radio Materiel, Elementary Electricity and Radio Materiel, and Radio Materiel. He had served one year, three months, and seven days, according to his Notice of Separation. And he was never sent overseas. He was very lucky.

The family archive includes a folder for Olsen, Earle that contains a crumbling manila envelope labeled Official Records; in it a booklet from the War Department explains that the Seaman First Class was responsible for “a number of routine duties connected with anchoring, mooring, or docking a vessel, such as taking soundings with a lead line, handling mooring lines, rigging a gangplank, and handling anchor chains.” It is much easier to imagine my artist father tinkering with a transistor radio than doing any of those tasks. Under Related Civilian Occupations, the brochure suggests how these skills could transfer to the transportation, logging, construction, manufacturing, and mining industries.

In case you’re wondering, only the last few paragraphs about Earle are actually in my memoir about my father’s art career. Andrew Sr.’s naval service is not relevant enough to include, but this Substack can be a place to park some interesting research that I don’t know what to do with. The question of what is “relevant” to the “main story” remains tricky to determine. There is something curious to me about my family’s relationship to the Navy that I can’t pinpoint. For example, why did my grandfather take so many photos of his sons in sailor suits? In another post, I speculate that they may have been studies for Sailor Jack when Andrew worked on the Cracker Jack box. My father was the least militaristic person you can imagine but he relished his association with the Navy. His military experience was atypical of his peers — who mostly fought abroad and came back changed — and atypical of my friends’ parents, who were more likely to be Vietnam War resisters than World War II veterans. In the end, my best guess is that Earle liked the stylishness of the Navy. His favorite color was dark blue. He liked double-breasted jackets with brass buttons. He loved Leonard Bernstein and Jerome Robbins’s Fancy Free (1944), and the movie version of On the Town. As usual with my father, it’s all about the aesthetics.

Please like, share, or leave comments and I will respond. Welcome to my new subscribers! (Most of my pieces will actually be about art—!)

You may not remember that early in this research I took out all the family records I had stored in my basement and left them on a table under a water pipe…. See this post for more details.

BTW, I used this photo for another post in a different context — about all the photographs of cars in my family archive.