Last week I wrote about finding one of my father’s paintings. Another week I wrote about a painting I found and lost again. Spoiler alert: today’s painting is still lost. I was intending to go through all the “successes” before getting to the “failures,” but I read James Lee’s wonderful post on portraits this morning and impulsively changed my mind to feature my father’s missing self-portrait today instead. I had also been moved by Rona Maynard’s vivid piece on her artist father yesterday. Together these seemed like a sign with an arrow for me. So on this rainy day on Cape Cod I’ll start us out with an excerpt from my memoir set in sunny Spain….

It’s 6AM, July 2019, Reus, Spain. I’m in the kitchen of the house my family rented for our first-ever reunion. Mother, sisters, brother in law, nieces and nephew, husband, daughter. My father has been dead for eight years. Now, here, I’m exposed, upset.

My father’s self-portrait is gone. And other paintings are missing. When I complained about it I somehow ended up fighting with my sister, fighting with my husband. That night I lay, motionless, next to him, trying not to take up space, wishing I could run away.

That painting took up too much space: we couldn’t divide it all so we left some in storage near my father’s home. My father’s surviving art was problematic: a lifetime of work is bulky. Some of it was oversized. One close-up head of my mother took up most of one wall in his dining room, one of three portraits of her that I know of. Many would be difficult to hang anywhere. What to do with the large painting of a nude man against a cosmic background of planets and spheres? My father lived in a three-story Victorian house. These paintings would be impossible to hang in our smaller homes.

But there were a few we all knew we wanted to keep— or knew we couldn’t easily let go of, like the two tall narrow paintings of elderly figures, which we thought of as portraits of my father’s parents. The old man was dressed in a raincoat, as I recall, and didn’t particularly resemble Grandpa Olsen. The old woman, though, in her fur coat and styled hair, was “definitely” Grandma Olsen, we thought. We hadn’t known what to do with those— there were three of us and two paintings and they weren’t the kind of paintings you could easily display just anywhere.

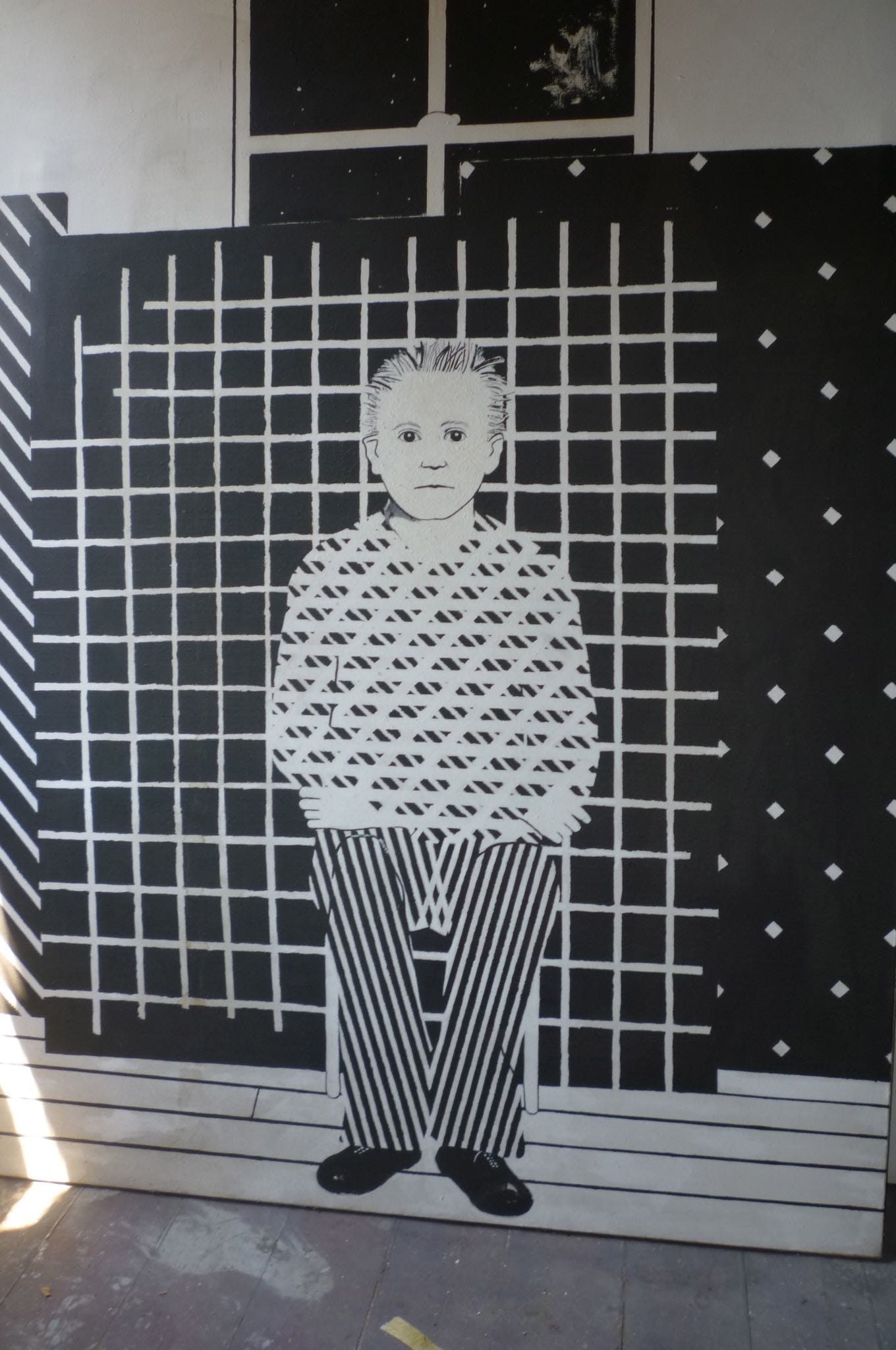

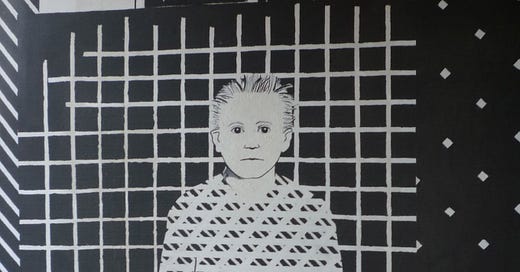

In another large portrait, shown above, my father painted himself as a young boy, sitting in an armchair looking straight out at the viewer. Behind him is a grid of black and white lines, but it’s the boy’s expression that always grabbed me—wide-eyed and innocent. Each hair on his head was singled out in a vertical spike. What was ahead for him? Who is he looking at? As a self-portrait it has a generic composition but it’s poised (or posed) at the cusp of my father’s work in abstraction and realism. Offhand, I can’t think of any other self-portraits he drew or painted, though he made other images (like the nude I mentioned above) that combined realistic figures with abstract backgrounds. But this one is so vulnerable, before he grew up to become my beloved and difficult father.

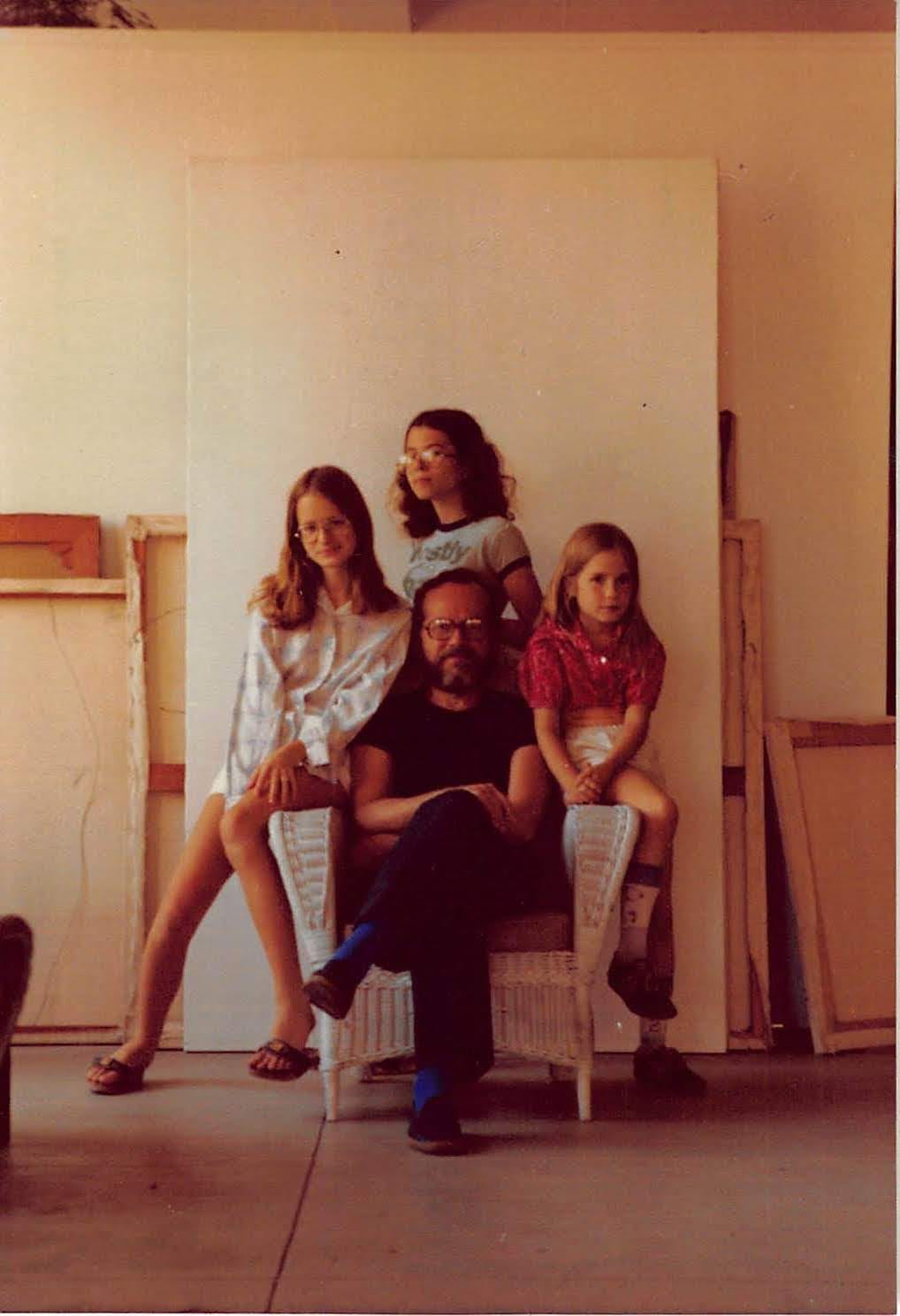

Compositionally, the self portrait resembles the family photograph of my father in his armchair, encircled by daughters (shown below— does he realize he is echoing that photograph, replacing the three daughters with three paintings?). It feels like a visible representation of the past he tried to erase by leaving the Chicago of his childhood. Early in my memoir I ask rhetorically, where do art and design intersect? Now I would answer: in the geometric quadrants of my grandfather’s design for a Kleenex box and the grid behind my father’s Boy in Chair.

That painting, which was “mine” in the sorting we did after my father’s death, is missing. I think. We made no complete inventory of which paintings went where.

Here’s what I can reconstruct:

Four years after my father’s death we discussed getting the large paintings from storage. I write my sister, “I wonder what happened to Boy in Chair?”

The emails taper off.

Nine months later we get an email from the storage facility that we have to collect what’s left. We agree to keep the two large portraits of our mother. I send my sisters an email: “Let's include the grandma painting too if you're taking them off the stretchers to store. I'm not sure what else is there but I'm okay with you donating it or you two deciding about the rest on the spot.” (Have I forgotten about Boy in Chair? Where else could it be?)

My sister and brother-in-law go to pick up the art. They are doing us all a favor. Somewhere there’s an email where they mention rolling up three large canvases. There’s no mention of which ones or what happened to the others, and now no one remembers. My anger spills out in every direction, four years later and thousands of miles away. If I forgot about claiming Boy in Chair I have only myself to blame.

The next morning in Spain I’m up too early. People are starting to rise as light enters the kitchen. I can see the sun as a bright red ball over the horizon. Soon it will be hot here in Spain. Time for me to go running, to escape.

It is my father’s death, of course, that I’m mourning in my grief for the lost paintings like Boy in Chair. The painting is gone because he’s gone, and the hero-worship I felt for my father when I was the same age as the boy in the chair is gone too. The man who filled the wicker chair in our family portrait is gone. In one drawing he called “3 Graces,” he sketched his three daughters surrounding an empty chair.

It’s difficult not to edit and revise these excerpts as I post them. Today I did indeed excise names and some family references, as well as some of my own melodrama. (It’s unseemly.)

Although we’ve lost the original, I do have another reproduction of Boy in Chair that I could have used for this post. But, frankly, I can’t resist that footprint in white paint on the floor, the trace of my father’s living presence right up against his painted black shoe. “Footprint” is another word we use for a personal stamp (literally an imprint of a body), like an artist’s eye. Self portraits say “I was here” and the footprint photo does so doubly. I’ll include a different unedited image below so you can see the painting next to another oversized portrait (modeled on my mother, we thought, though she doesn’t remember sitting for it). Both had been stored in his dusty attic for decades (the ancient plaid wallpaper adds some extra geometry).

So be it. Maybe some of the lost paintings will indeed show up, but I mourn them anyway.

Resources:

You can find other examples of my father’s portraits here. In the 1980s, he made a series he called “The Human Comedy” and my sisters and I called “Blue Sky.” I’ll write about those too someday.

- wrote the post I mention above on painting portraits, with many wonderful examples from his own work, including Self Portrait with a Head of Flowers that he leaves unresolved and mysterious….

- wrote about her own artist father here in another post I found inspiring this week. The relationship of art and family is central to her piece too.

I very much enjoy the conversations sparked in Comments and the way a restack from one writer can help me find another (h/t to Jeffrey Streeter for pointing me to Rona’s piece!). Thank you, community! I appreciate and respond to all comments.

There is something uniquely painful about losing the person, and then, not just any physical reminders but creative work in which their animating spirit has been preserved. I have been really moved by these essays. There is also the pathos of lost artwork, even if it is by an artist one hasn't met. I recall my late mother, in the midst of her Swedish death cleaning, shipping off her collection of original paintings by Canadian Ojibway artist Benjamin Chee Chee to a gallery in Toronto, which had agreed to sell them for her. The gallery owner died soon after, and everything he owned "disappeared." She could not track down an executor, an attorney, or any contact. Was an 80 year old woman going to pursue this further from another country? Maybe I will come across these paintings somewhere, someday.

Victoria, I love the self-portrait of your father. It feels so modern, so anticipatory of the work of younger artists to follow. As I read, I kept thinking, Where is the Boy in Chair? But that's who you continue to look for in this wonderful memoir. A possible title?