I began this mini-series with this post about finding a black-and-white reproduction of a painting by my father filed under the miscellaneous Os in Thomas Hess’s papers at the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian Institution. Hess was the influential editor of ArtNews in the 1960s. Later, I ended up finding the painting itself for sale on eBay and (spoiler alert) decided to let it go.

That research gave me the idea though to try to track my father’s other early paintings, mostly from his Bodley and Borgenicht exhibits in 1955 and 1958. Any paintings that were lent to exhibits by collectors were marked as such in catalogues so I knew that Richard Sisson had bought “Waterfall at Sandy Hook,” which reappeared in a show at the Rhode Island School of Design museum in 1956 and then the Borgenicht in 1958. A Dr. Lewis L. Heyn of Princeton, New Jersey had purchased “Panorama” and a Miss Caroline Schultz of Great Neck, New York had purchased “Trees.” Max Kahn, a faculty member at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (my father’s alma mater), bought “The Grove,” which was chosen for display at the Whitney Museums’s annual show in 1956. At first I had no luck finding any of those individual borrowers or those paintings (many rabbit holes here, stay tuned!); institutional collections, however, were easy to track.

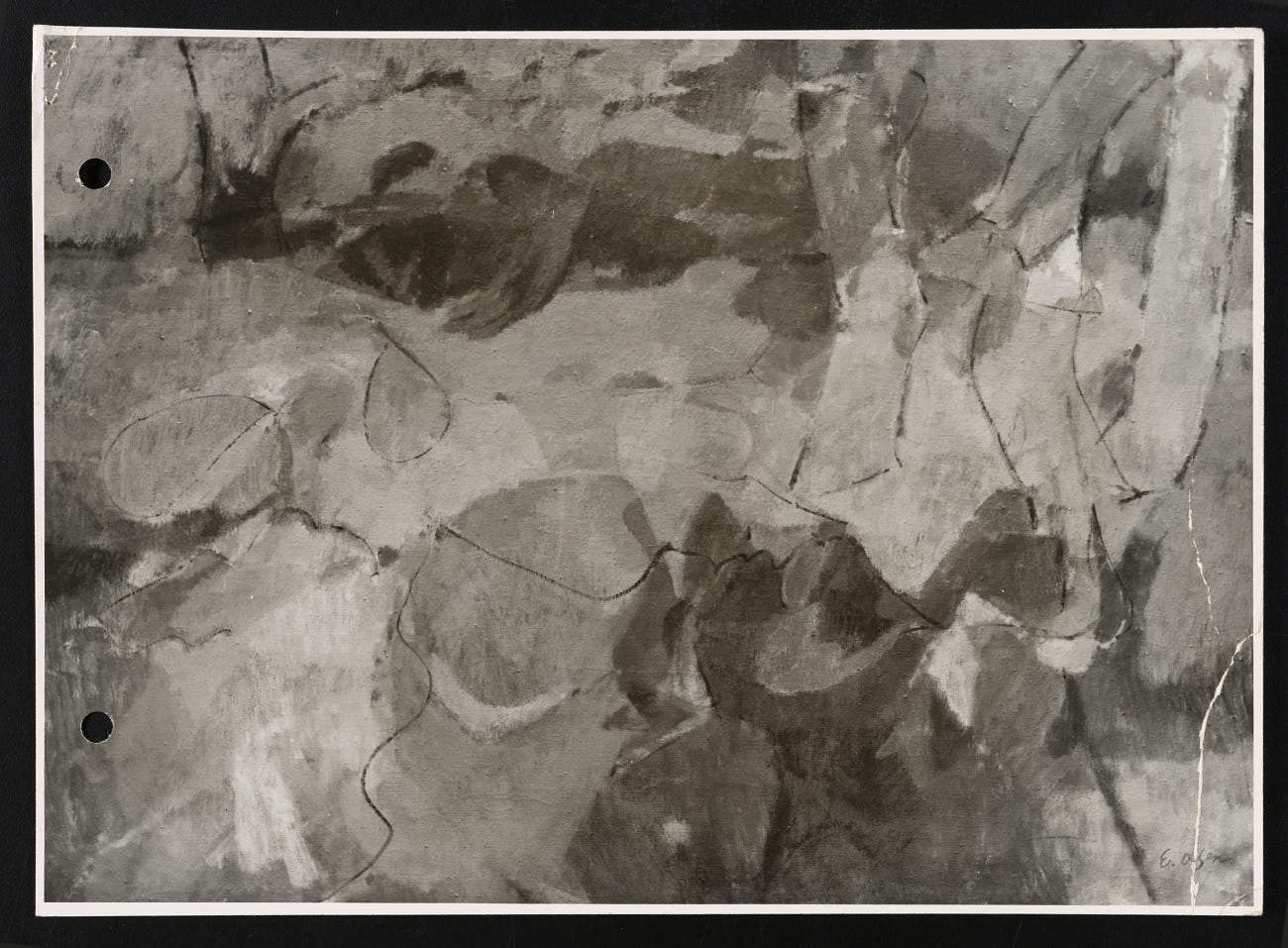

For example, I quickly found another of my father’s works in the Smithsonian’s digitized archives. In 1965 Grace Borgenicht Brandt donated one of my father’s paintings from his 1958 show at her gallery to the Finch College Museum of Art on East 78th Street. A folder under his name includes her letter and a reproduction of the painting itself, called “Fall Woods” (1955). I had never heard of this college, though I grew up in New York City, and it turned out to have an interesting history of its own (more rabbit holes). It was founded in 1900 by Jessica Finch, a Barnard alumna like myself, as a preparatory school for women, then became a college for women in 1952. From the start it emphasized hands on learning, with a strong art program.

Finch College’s museum was founded in 1959. Under Elayne Varian’s direction, it became an influential supporter of contemporary artists, though my father never seems to have exhibited there. Then, Finch College went bankrupt in 1976 and the museum’s administrative and exhibition records went to the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art. Their finding aid includes one sentence about what happened to the art:

“the permanent collection was sold at that time, and the proceeds were used to pay Finch College employee salaries.”

A folder labeled “Paintings out of Museum, circa 1970-1974” includes handwritten notes about various destinations for different works. There were Rauschenbergs and Frankenthalers to place, Lichtensteins and Stellas, even a Picasso. Someone scratched out directions on a yellow legal pad, noting the original locations like “Admission Office” or “Snack Bar.” My father’s painting, along with many others, ended up at Chalk House, a building around the corner on the Upper East Side. And then the trail vanishes.

Except there’s one last curious rabbit hole: Chalk House was named for its real estate developer, an O. Roy Chalk I had never heard of. He had a wide-ranging career: he was born in London, grew up in the Bronx, and started his career in the transportation industry. According to his obituary in the New York Times, he founded a commercial airline in Central America, bought a railway used to transport bananas there, and owned the DC transit system for awhile (who knew it was even possible to buy a city’s transit system!). He founded the El Diario/La Prensa newspaper in New York City as well as the American-Korean Foundation. He collected art and unique gems, leaving a Chalk Emerald to the American Museum of Natural History and a bust of Thomas Jefferson to Monticello. He got around— and the building on 77th and Lexington Avenue is still named for him. Many of the works from the Finch College Museum of Art’s collection seem to have ended up there, though I don’t see any connection except proximity.

It’s normal, this randomness. It’s a miracle the handwritten note was findable at all. And digitized. I can’t complain.

I confess this isn’t exactly the same excerpt as this section of the memoir. I added the rabbit hole about O. Roy, for example, on a whim. In general, I can be looser here than there.

But I didn’t add a new insight I just had now, writing this: was my father’s painting moved from Chalk House instead of to it? Perhaps the museum had loaned works to a nearby building for more display space. The handwritten pages are vague and incomplete. If the collection was liquidated to pay salaries, I found no record in these archives of the proceeds.

Another confusing insight to come back to sometime: despite the research I have done, there is more that I am avoiding. I have not gone to Chalk House to look at the lobby. That might be fruitless, but I haven’t even tried. Neither have I compared the black-and-white reproduction of “Fall Woods” to other reproductions of my father’s work to see if they match. I only want to know so much— more, but not everything.

Welcome to all my new subscribers! Instead of an exercise this week, I’m including a poll so I can get to know you better as this newsletter evolves. Please help me out by responding— as always, I appreciate feedback.

This was so interesting, Victoria. I went down the O. Roy Chalk rabbit hole (great initial!). He seems to have been quite a colourful character. He seemed like a figure out of "Nostromo" at first glance, but then his experiences in Central America made me think of the work of one of my favourite Latin American writers, Miguel Ángel Asturias (who will doubtless make an appearance over at English Republic of Letters at some stage). Thank you for that.

And I hope you can track that painting down!

i love the sleuthing!