Turning Points, Part 1

What happened to my father's art career?

At this midpoint of the year I offer two possible turning points for my father’s life and career. I also just hit the halfway mark in the communal daily reading of War and Peace with Footnotes and Tangents. It’s a sign.

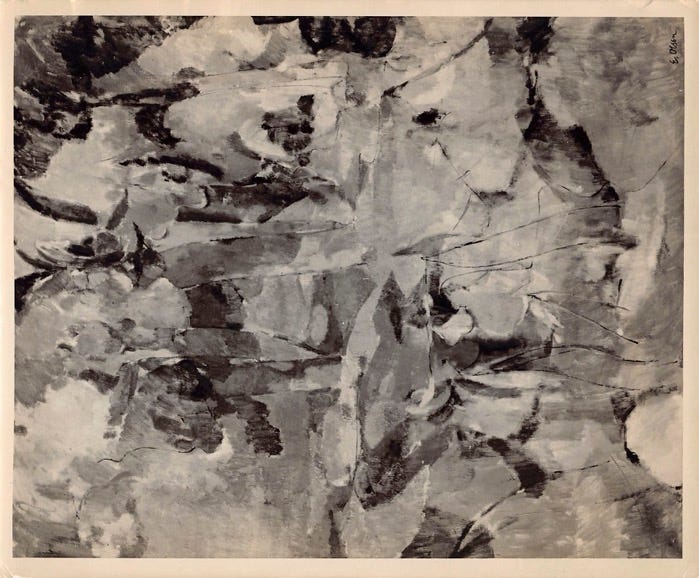

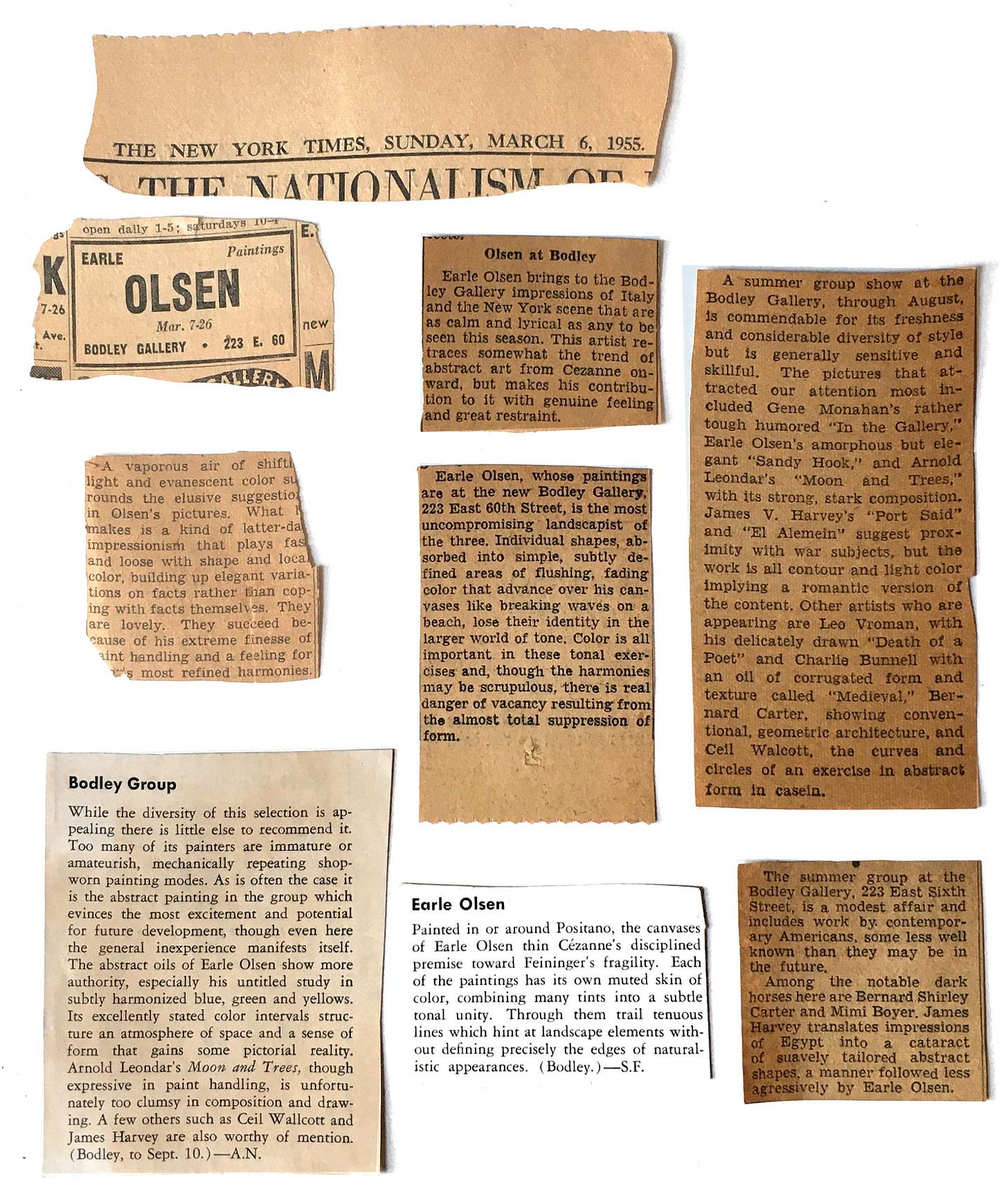

My father kept reviews of his work in an envelope marked REVIEWS. I’m as reluctant to read them as I am the reviews or comments about my own work. It’s too personal. I avoid them until I can’t any more. When I open the envelope they spill out like confetti, clipped from newspapers like the New York Times and the Herald Tribune. These clips are mostly positive, often citing his use of color. One critic rhapsodizes that

“Earle Olsen bring to the Bodley Gallery impressions of Italy and the New York scene that are as calm and lyrical as any to be seen this season. This artist retraces somewhat the trend of abstract art from Cezanne onward but makes his contribution to it with genuine feeling and great restraint.”

Another writes of

“a vaporous air of shifting light and evanescent color… building up elegant variations of facts rather than coping with facts themselves. They are lovely. They succeed because of his extreme finesse of paint handling and a feeling for (illegible) most refined harmonies.”

One complains about a summer group show but makes an exception of my father:

“The abstract oils of Earle Olsen show more authority, especially his untitled study in subtly harmonized blue, green, and yellows. Its excellently stated color intervals structure and atmosphere of space and a sense of form that gains some pictorial reality.”

Stuart Preston in the New York Times seems to begin with lyrical praise, then shifts:

“Individual shapes, absorbed into simple, subtly defined areas of flushing, fading color that advance over his canvases like breaking waves on a beach, lose their identity in the larger world of tone. Color is all important in these tonal exercises and, though the harmonies may be scrupulous, there is a real danger of vacancy resulting from the almost total suppression of form.”

This suggestion of superficiality will dog my father’s critical reception. Reviewers return to phrases like “amorphous but elegant.” And they often compare him to someone else: Cezanne, Feininger, or contemporary artist Tal Coat.

I find other reviews by searching through periodical databases and they are often worse (these are, after all, the ones my father saved). In April 1955 Laurence Campbell of Art News wrote of Earle’s one-man show at the Bodley:

“It seems painting with a piece of someone else’s painting in mind. As sensations landscape they are limited, undernourished. But his colors, limited to a few greens and tans, are restful. $60-$200.”

Earle and his friend James Harvey exhibited at the same galleries—like the Bodley and Parma—so they must have been especially competitive. Jim was represented first by the Roko Gallery and then by the Graham Gallery. Earle started with Bodley, then moved to Grace Borgenicht, who gave him a one-man show in 1958. This would be the pinnacle of his art career but he was advancing steadily, with a show at the Rhode Island School of Design in 1956 alongside Hedda Sterne, and paintings in the Whitney’s annual exhibits of 1956 and 1958. The Whitney had bought a work on paper for their permanent collection from Borgenicht; another painting ended up at Brandeis University’s Rose Museum of Art.

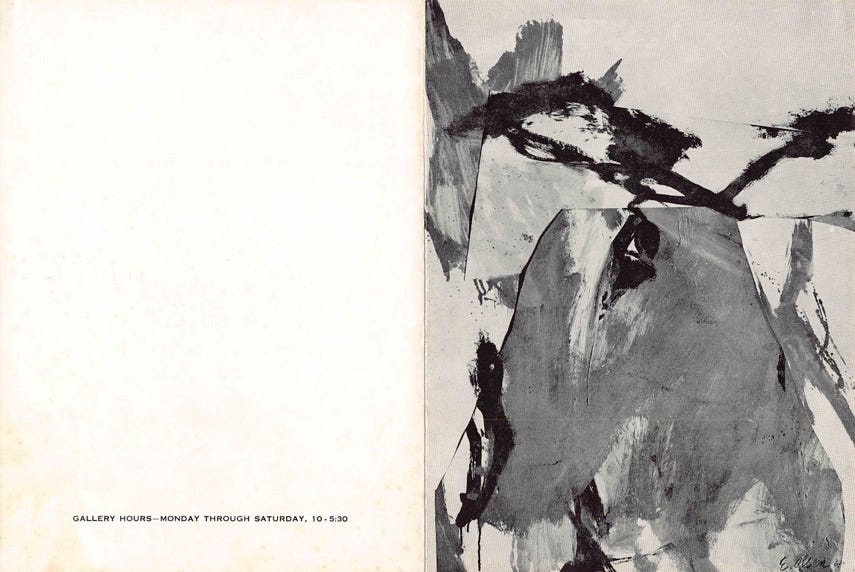

Then something happened. Or something didn’t happen. I’m not sure. But by the early 1960s Earle is out at the Bodley and Borgenicht; his only subsequent show in New York City was at the Angelski gallery in January 1962. Art critic Brian O’Doherty of the New York Times covered that show in two sentences:

At the Angelski Gallery, 1044 Madison Avenue, Earle Olsen is showing expressionist abstractions of the de Kooning variety. They are professional works with all the virtues of sensitivity and good color but lack the power to pull them out of the usual.

Was that a killing blow? (I taught Brian O’Doherty’s essays on art for years without knowing he had reviewed my father’s work. I never got up the nerve to contact him: what would I have said? would he even have remembered that show? He has since passed away.) By 1962 my father had met my mother, and she remembers how devastated he was by that review. In a 1963 oral history for the Archives of American Art Jim Harvey is blunt: around 1958 Earle’s work became “derivative” and Borgenicht had to “shove him out the door.” According to Jim, Earle not only took on the “the technical aspects” of de Kooning and Kline but also the subject matter so his work began literally reproducing them:

He just sort of tumbled I mean, after withholding from the whole thing [Abstract Expressionism] for years…when he finally did, you know, come to it, he came to it with such a bang and a wallop that it almost destroyed him, I think, and I can almost say that even now he still hasn't recovered. I mean, in seeing his painting you can't find any of him in it.

It’s a startling condemnation to come from a friend, in a very public forum. The purpose of these oral histories was to document and preserve exactly these contemporary opinions. It’s possible that my father agreed with or accepted Harvey’s view. In the early 1960s he took a full-time job with Kulicke Frames. Over the next decades he watched his Abstract-Expressionist peers rise in stature, then new artists and movements overtake them (stay tuned for my post on the Warhol connection…). He spent the rest of his career ordering, measuring, and installing section frames for their exhibits. He kept painting but he essentially gave up on trying to sell or display his work.

This excerpt is itself a turning point in my book; it comes midway into my memoir, and now midway through this calendar year. A hinge comes in handy in telling any story. It provides a shape to differentiate the sections and track forward motion. You can see Jim Harvey constructing his own narrative in his account of my father’s work: the vocabulary of a rise and a fall. To mark progressive change, novelists can shift time period or point of view. Filmmakers can shift location by cutting from one place to another. Biographers and memoirists can use a before-and-after moment to organize a life story, though where to put it is a subjective decision.

“On or about December 1910,” Virginia Woolf claimed, “human character changed.” In the essay “Mr. Bennett and Mrs. Brown” she attributed this change to the shift in class relations in early twentieth-century England, and its corresponding depictions in novels. But by the time she wrote about that shift in 1924 she had the hindsight to also understand the impact of the Post-Impressionist show organized by her friends Roger Fry and Clive Bell to introduce English audiences to the then-radical art of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Cezanne, and Seurat. Influential exhibits are useful hooks to hang art-historical changes on. Similarly, history textbooks may choose a a decisive moment to start a war or a social movement. Yet, halfway through War and Peace, where I’m at now in my year’s reading, Tolstoy resists any single explanation for the rise of war in Europe in 1812:

“Nothing is the cause. All this is only the coincidence of conditions in which all vital organic elemental events occur.” (Book 9, chapter 1)

In other words, a turning point should be understood as a device, an organizing structure.

I see my father’s life story as divided into several possible turning points but one lands in the early 1960s, as I describe here. Next week, for part two, I’ll offer another possible interpretation.

Please like, share, comment, etc. This is how I get to know you as readers and writers.

Writing exercise: Find a turning point in the life’s story you’re telling. It need not be the only one, but a credible one. What does it turn from and to? Where does it belong in your own narrative? How do you interpret it?

My father worked for Bob Kulick in the mid 50s. They were lifelong friends.

The comparison with Roger Fry’s post-impressionist exhibitions is really interesting. Sometimes I think that cultural shifts are triggered by a critical mass of events. The post-impressionist exhibitions. Avant garde performances by the Ballets Russes. Charlie Chaplin films. Jazz. Cubism. The publication of In Search of Lost Time, Ulysses, and Mrs Dalloway. Like a boxer knocked to the ground by a devastating succession of blows, eventually the old guard collapses and a new era unfolds.