Last week’s post on my father’s friend Winston reminded me that I had planned to write character sketches of some of the people who crop up in my memoir about my father’s art career. I wrote one already about my grandmother Elsie Anderson Olsen. This one will try to describe a complicated figure in my family’s story: my grandmother’s youngest sister, Marie.

During the 1970s my divorced dad would bring his three daughters down to Florida for an annual visit to his widowed father. We’d swim in a hotel pool and eat ice cream, and sometimes make a side trip to Disney Land or Marine World or Sanibel Island. It sounds like fun for a kid, but even then I felt the tension. My father and grandfather didn’t particularly get along; my grandmother and my father’s older brother had both passed away by then and they were stuck with each other. On the sidelines of this drama, making wise cracks, was my Great Aunt Marie, who lived near my grandfather in Daytona Beach. She was friendly enough, but I was afraid of her back then. Look at her portrait, above. That lifting eyebrow. The shadow of a smirk. She was scary!

In 1977, when I became interested in genealogy, I wrote Marie for information about her family. Over the years, she sent me letters stuffed full of family stories and images, carefully labelled in her hand with dates and names of everyone present. According to Marie, her childhood had been difficult: her mother Alice (born Elise Stieber) was a well-educated round-faced young woman from Germany who arrived in Chicago around 1891, became a governess, and somehow fell into marriage with Henry Philip Anderson, a horse cab driver who was rumored to have made his money ferrying prostitutes to and from brothels. Marie reported that Henry drank a lot and disappeared for stretches of time. Each of the six kids left school after seventh grade to support the family: the girls became stenographers and the boys took up odd jobs. Alice managed the home as best she could and once kicked Henry out, Marie said.

One letter was filled with Marie’s own eclectic life story: “I went to work at age 15 and being much more interested in dancing and having a good time was fired from the first 8 jobs I had much to the disgust of my whole family.” She worked as a wardrobe mistress in the theater, a taxi dancer (ten cents a dance), and at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933.

Oh, and I almost forgot - I managed to marry at age 19, hitchhiked from L.A. to Yelm, Wash. on my honeymoon (we were the hippies of the thirties!) Terence O’Leary was the poor soul’s name and we worked on farms from state to state. My experiences there would fill a book and some were very funny.

The couple divorced when he entered a monastery. She became a secretary (all her letters to me were typed) and was one of the first women in Chicago to join the U.S. Marines Corps Reserve in 1943. She was opinionated. She forwarded me copies of her incensed letters to politicians on subjects from gun control and abortion rights to the Supreme Court Justice hearings for Clarence Thomas. In 1987 she wrote to the President of the National Organization of Women after a convention in Philadelphia, in which she bemoaned the “disheveled” appearance of her fellow attendees and the disservice they did to feminism by not being better groomed. When I asked her about her life and feminism in a 1991 exchange, she was blunt:

I hate to disillusion you, honey - but in my youth feminists in any form did not openly exist - those of us who scratched and fought our way up the puny ladders we were exposed to were considered odd, different, man-haters, sure-to-be-old maids, because we openly admired the suffragettes who got us the vote, but mostly we were so busy trying to make a living because the depression was a great part of our lives.

Much later she described her sister as having lived "in complete subjugation" to my grandfather Andrew. “Elsie’s relation to a woman’s movement - none,” she wrote.

When Elsie died in 1968 Marie encouraged her widowed brother-in-law to join her in Florida. She supervised his move in 1970: hiring workers to clean and do yard work and doing much weed-pulling and maintenance herself, sweating in the heat. In her letters to Andrew, Marie complained about her finances and teased him about his "harem" of admirers. He started seeing her almost daily. She was a lesbian, but that didn't stop Andrew from proposing to her as a way of ensuring she would keep taking care of him. I remember my father laughing that his father didn’t seem to understand that the “friend” Marie lived with was a romantic partner. I knew Marie was gay decades before I found out that my father was too.

Marie turned Andrew down. In a 1979 letter to my father going over estate matters, Andrew noted this as a moral point in her favor: “Remember that if I had married your Aunt Marie your inheritance would be much less than what you will get by law. Many conniving women would take advantage of me to gain so much.”

Nonetheless, when Andrew died in 1980 Marie and my father squabbled over their shares of Andrew's estate, which never generated as much income as either wanted or believed they deserved. Marie inherited his house. My father inherited Andrew's Cadillac and the photos and other documents I draw on now, moved from basement to attic to basement. They both received lump sums of cash, but the balance of the estate was left in trust to pay for his three granddaughters’ educations. Though my father must have known about the will, it still must have hurt his feelings. It must have confirmed his suspicion that his father didn’t trust him with money. At least, that’s my most generous interpretation for why my father spent the next decade trying to get his hands on it. “Florida” became synonymous with the bank trustees and lawyers who stood in his way. “I think I should dissolve the trust,” he’d say over a glass of red wine, as if it were his.

In 1991 the inevitable crisis erupted. My father and Marie asked me and my sisters to agree to dispersing the remaining balance in the trust to them. My sisters and I were all in our twenties by then; our college tuitions had depleted the account, but two of us were still in graduate school. Marie wrote to the three of us, defending her care of our grandfather and describing her financial straits: “the bank here has advised me that they are waiting to hear from you girls in response to their letter. I didn’t realize that my financial security would rest in your hands, and I am not sure that that was what your grandfather meant.”

In 1991 I was just converting to word processing documents and I still have a printout of the reply I sent to Marie:

It seems to me that the bank is willing to cooperate with any plan that meets the approval of all five of the trust beneficiaries, so I think we should be able to figure out a plan that keeps everybody happy….I can well imagine how unpleasant it is for you to discuss this with us, and to require our approval, but believe me it is equally uncomfortable for us, and we’ll try to be flexible and sympathetic.

Marie replied, “I’d really prefer to leave the discussion of the trust matter to my attorney than run the chance of losing the wonderful rapport we have at present.” She did explain, though, that Andrew had always told her that she and Earle were his beneficiaries and he would “help” with our education “IF the trust funds permitted it.” The capital letters were hers.

I wonder now that it didn’t occur to me to ask anyone for help with this negotiation. The person who should have been looking after my interests—my father—was clearly looking after his own. My sisters and I came up with a compromise and signed the papers. I never even consulted a lawyer.

My parents, who rarely agreed on anything, both believed that Marie was always angling after Andrew’s money. They thought she lured him to Florida to cheat their children, the “heiresses” as Marie called us, out of their inheritance. But she did take care of Andrew for the last sixteen years of his life, and why shouldn’t she have earned something for all that thankless work? My father certainly hadn’t exerted himself to do any of it. Despite the legal and financial entanglements, Marie was always kind to me, signing her letters “you have my love.” In one letter she wrote,

I am so proud of you and your sisters. It is unfortunate that your grandparents aren’t alive to know of your individual successes. Andrew would be so pleased - and God love her, your grandmother would regard you three with awe….having so limited schooling.

In her own way, Marie mothered a whole generation of her family, and fiercely supported the women. She stood up for herself in ways that I admired, even when it made us into antagonists. I didn’t begrudge her her share of my grandfather’s estate, such as it was. The money never lived up to anyone’s expectations, and reinforces how much Andrew must have deeply believed that it was the source of all his value. Sadly, my father and Marie proved him right. Neither of them liked him much. I didn’t either, at the time. Now, though, I am grateful that he thought ahead enough to protect my sisters’ and my educations.

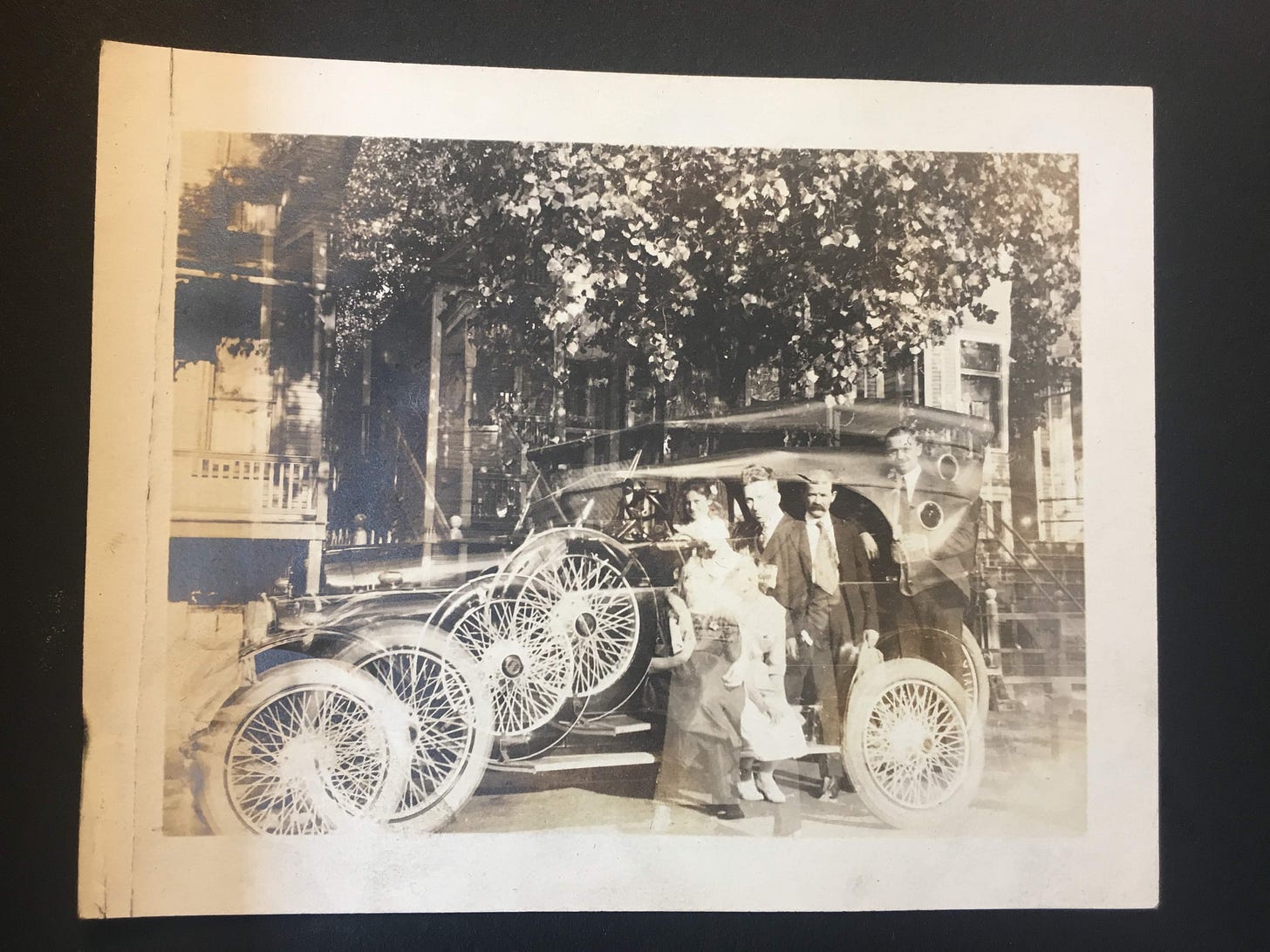

When Marie died in 1995 my father’s cousin Alice sent me a videotape of her funeral at Arlington National Cemetery and a fancy linen tablecloth—presumably from Andrew’s house—embroidered with the paternal O. It was yet another artifact to be interpreted, like the overexposed family photo of the 1920s car I wrote about earlier, with a young Marie at the wheel. The character sketch I wrote about my grandmother Elsie focused on the objects she left behind— because I had no letters and no memories to round her out. But in Marie’s case her voice is everywhere in the family archive— sharp and amused, fond and sardonic. She was a three-dimensional, contradictory character, who can tell her own story and represent herself.

Please like, share, and leave a comment. I appreciate the support!

REMINDER: I’ve opened a Calendly link for office hours so readers can schedule 15 minute introductory calls with me on Google Meet. No agenda needed, except to talk about research and writing— mine or yours. I’m just interested in getting to know you.

COMING IN MAY: a special double posting on the life and death of my father’s brother for Memorial Day….

What a glorious finish: "She was a three-dimensional, contradictory character, who can tell her own story and represent herself."

And what a challenge to write a balanced sketch about someone with so many angles. Well done!

I love stories about real people in all their dimensions. "A complex character" indeed! Nice work!