Road Trip

The search for my father's paintings, part 6

This post is part of a series I’m writing about searching for my father’s lost or missing paintings. I’ve written about one I found and lost again, one I never knew about, one I loved and haven’t (yet) re-found, and two I found against all odds. Last week I wrote about one I took a ferry to visit in person. This week’s involves a road trip.

It started when I picked up the rental car. The company had upgraded me and the car in front of me was more like a truck than anything I was used to driving. It had no key. The nice man kept asking me questions about what extras I wanted to accept or decline. I could feel anxiety rising up my throat.

My plan had been simple: rent a car in Massachusetts and drive to upstate New York, where I would visit another one of the few surviving paintings my father had made in the 1950s. Or rather, I’d visit its owners, a welcoming older couple who had inherited it from their friend and neighbor, an art collector who had worked at the gallery where my father exhibited. I had found them in 2021, when a random internet search turned up another gallerist who had once worked at that gallery and remembered the painting. I corresponded with the owners and in 2023 I finally made the pilgrimage to meet them. I took a deep breath and hoisted myself into the car and started pushing buttons. I could do this.

I managed the traffic on the Mass Pike, stopped in the Berkshires, and stressed about what to bring the couple upstate as a thank you gift. I bought chocolate, then changed my mind and chose some artisanal bread. It was a cold, wet weekend and I worried I didn’t have the right clothes, then worried about driving on wet roads. In fact, I thought nonstop about bailing and going home. I could return the car early! Say I was sick and hide out at home! This was already an expensive trip– emotionally and financially– and what was I even expecting to discover? I already had a photo of the painting, called Waterfall at Sandy Hook, so why see it in person anyway? My sisters and I had sorted through thousands of our father’s artworks when he passed away in 2011, choosing our favorites to keep, storing some, and throwing others away. At the time, there were too many. It was all too much. Now, I was looking for anything else I could find. This trip felt like a box to check off, a loose end to tie up after finishing the manuscript.

After another four hours of driving through rain I made it as far as Corning, where my hotel turned out to be under renovations. I dragged my bag through dark empty corridors, listening for any voices. The ceiling light flickered and a sign warned that the water would be turned off for several hours, though the rain kept up outside. The hotel clerk called my room to tell me my car was lit up and running in the parking lot. I wished I had persuaded someone to come with me.

The next day another hour at 80 MPH got me to the home of J. and R., who met me at the door before I could knock. Outside the house looked like any of the others on the street: it was painted a cheery yellow, with a covered front porch. Inside, however, every room was packed full of antiques and collectibles from every style and period. Patterned wallpaper covered the walls and rugs lay on top of each other on the floors. R. was warm and talkative in a brightly-colored scarf. Her mother had been a painter. J. was earnest. “I’ve always loved collecting,” he told me. He was a tall man with a mustache that curved upwards into two circles. “I started with lamps when I was just a child.” Lamps! I marveled at the glass paperweights, the vintage clocks, the framed landscapes as they toured me around the first floor. Upstairs my father’s painting occupied a corner in their bedroom. “Where I can see it when I wake up,” R. told me. It was paler than I had imagined from the photo, with pinkish abstract clouds against a hazy background. “Thank you for taking care of it all these years,” I said.

They regaled me with stories of their friend, the collector Richard Sisson who had bought the painting in 1955, and his partner Peter Hanson, who had retired upstate after long careers in New York City’s art world. “It was quite a change for them!” R. admitted. “But we had so much fun, talking about art and hearing their stories. Richard had gone to Hollywood in the 1940s and landed one tiny role. We all laughed when we watched it on TV.” “There’s not much to do up here,” J. said. “But we had a great time. And when they started failing, we sort of took care of them.”

We walked as we talked and I started to relax as I listened. They bought only what they loved, combing estate sales and thrift stores, figuring out where to put it later. The overflow went into the church next door, which was deeded to their property. They renovated its interior and designed the open space to feel like a home showroom, with different living areas right up against each other. They threw Christmas parties under the stained glass windows and cozied up near the gas stove to watch TV from the sectional. It was a world unto itself, reflecting their shared lives and tastes. It was unlike any home I had ever seen, though my father too had loved and collected antiques. I marveled at its strangeness; these people were strangers, but their home spoke to me.

“Did Richard and Peter ever talk about being a gay couple in the 1950s?” I asked as we were winding down. Richard had been well connected to one queer art scene: he had known Glenway Wescott, the novelist, and George Platt Lynes, the photographer. My father may have known them too, but he didn’t come out to his daughters until the 1990s. He never talked about that world and we never asked. J. and R. shook their heads: “They never spoke directly about it. When gay marriage was passed we were sorry they hadn’t had the opportunity to benefit from it.” In an archive I had found a letter from Richard to a friend after Peter’s death, written with a shaky hand and grieving his partner of fifty years.

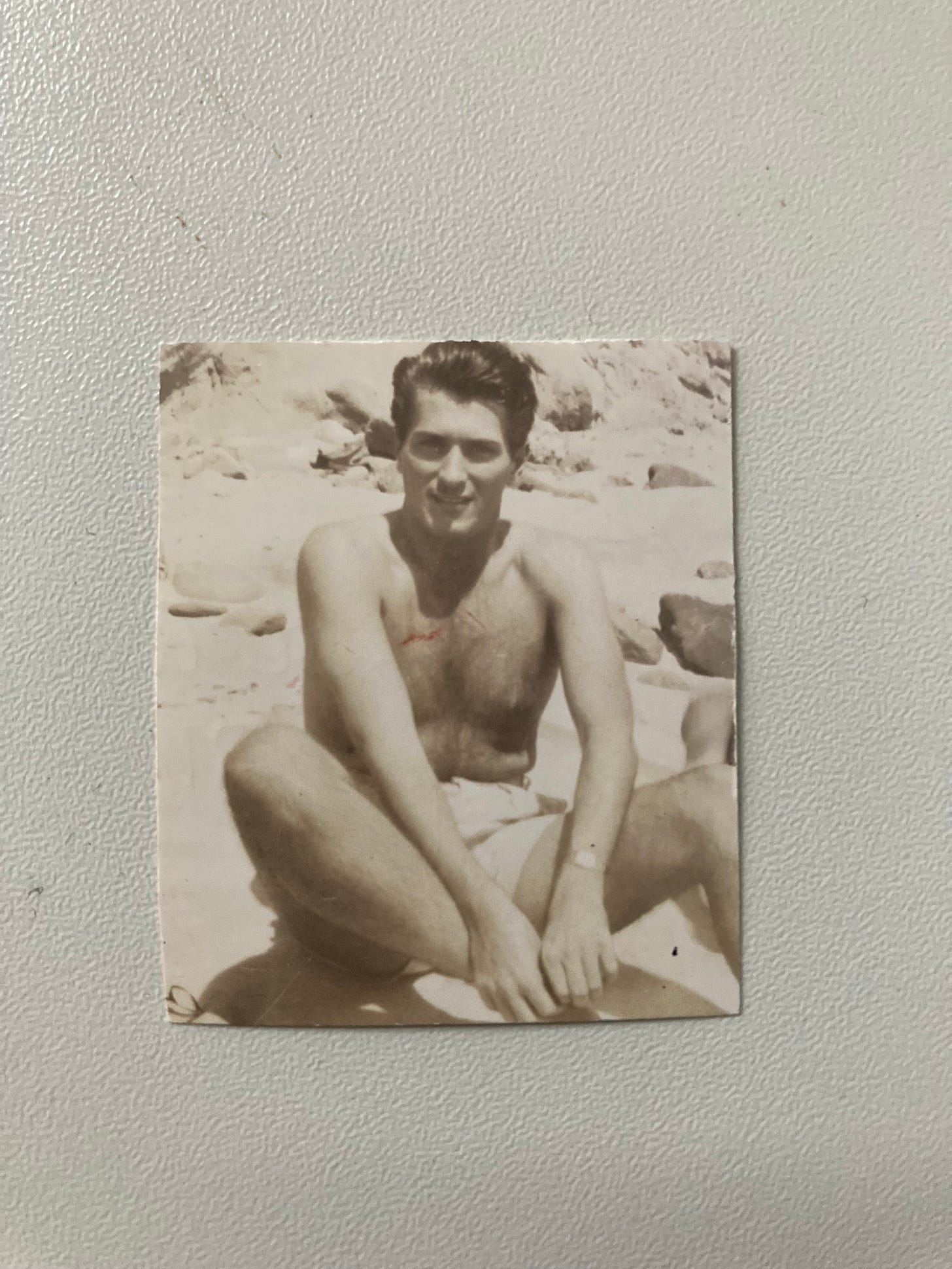

I left with a gift from R.: a small photograph of a young and glamorous Richard in a bathing suit, perhaps from his Hollywood days. I had learned nothing new about my father but felt inspired and even comforted to know about all these lives devoted to art, to see where art and love intersected. My father’s painting was in good hands and I had proven something to myself.

I have gotten out of the habit in the last few posts of analyzing my own excerpts but I’ll return to that briefly here. I am not sure I conveyed enough of my excitement at that visit— what it meant to me to meet these people and see their home, with my father’s work in it. There’s a reason I saved this story for last: it was tricky to write also because I was and am protective of these generous people and their privacy.

Why was the visit so meaningful? I think it was deeply moving to see the clear and uninterrupted lines connecting my father to Richard to this couple to me over seventy years. The painting itself forged those connections and I was astonished that J. and R. were as excited to meet me as I was to meet them. They loved this painting and extended that feeling to my father, and then even on to me. “Where art and love intersected,” I wrote above: I think I was also encouraged to hear Richard and Peter’s love story. I wish my father had found a relationship like that in his lifetime.

Writing exercise: I’ve neglected these writing exercises recently too and am still not sure if they are useful to anyone. But here’s one I could use myself: describe a memory or a scene in your writing project from an opposite point of view. In my case, what would this piece be like if J. or R. narrated it instead? What emotions or observations might surface then? It’s practice for view-finding and perspective-shifting.

Please like, comment, and share…. I am eager to connect with people. Thank you, again, for your time and attention!

Oh, Victoria, this is so touching. Starting from our analog world, we're still wrapping our minds around using these digital tools to preserve the context for treasured artifacts by combining photographs and words like this. I wonder if your new friends J & R might permanently associate your writing with the painting itself, either as a printout attached to the back of the canvas or a QR code referencing a link to this post, archived to the Wayback machine at Archive.org. The painting has a new home and a new life and it will carry on for generations. ❤️

Wonderful, delicately moving piece. So far this is my favorite. You're getting to the feeling beneath the words, the engine of the tale of finding your father, his work, and his place in the world. Utterly beautiful. Thank you!