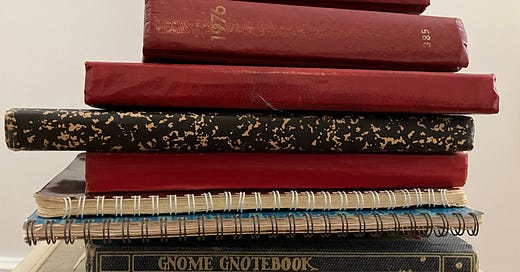

I recently descended into my basement in search of my old diaries. I didn’t, and don’t, want to read them. I just wanted them out on shelves instead of moldering in cardboard boxes. I found a few, in various formats. I also found a stack of elementary school composition notebooks, among which were two early pieces of writing that I reproduce to study here. They are mirror images— biographies of each of my parents, written just as they were splitting up.

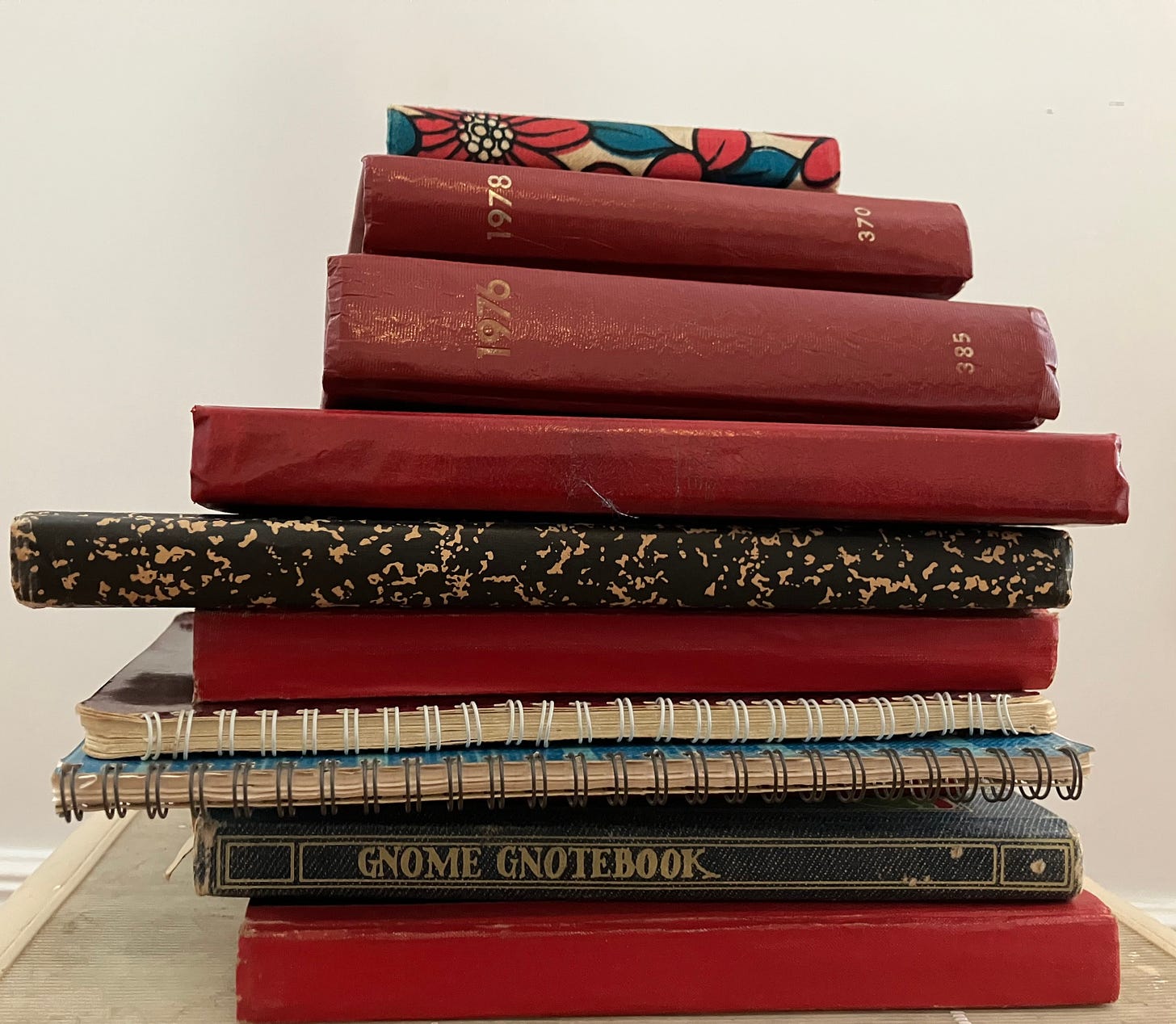

My father’s, undated, comes first chronologically, I believe, and includes a “final copy” and first draft. There’s stuff to like — for example, the vivid anecdote on that first page. I don’t remember that hornet story from any other telling, and my father rarely said anything nice about my grandfather. The Tarzan story is a happy, evocative memory— so child-like and so dated. This biography confirms some early family myths that were told and retold—about my grandfather designing the Cracker Jack box and my father painting on window shades as a child. It mentions the Japanese Bridge painting I still have on my wall. It reveals something new: that one of his pictures is hanging in his old elementary school. (Note to check that, but seems unlikely to still be true.) I also made mistakes in this account: my youngest sister wasn’t born in New Jersey; all three of us were born in New York City. The chronology ends in 1972, which is probably when I wrote this, in second grade. I made only a few changes to the first draft: I added one new sentence about my father’s job at Kulicke Frames, capitalized “Tarzan,” and corrected “there daughter” to “their daughter.” I don’t seem to have discovered the paragraph yet, and sentences lie side by side without any connections or hierarchy. I had no ability— yet—to prioritize.

Can I hear my own voice in this account? I see tiny details of my habits, like misspelling “untill.” I actually remember distinguishing until and till, which I had conflated, then learning when to use til. I hear my interests, emergent: the family and art, genealogy, an obsession with names. On page three I mention that my parents wanted to name “there son (if the had one) Eric or Peter Earle but they never had one” [sic]. There’s my father’s brother’s death, my sixth birthday in St. Vincent. It’s like a Greatest Hits album that will be played and replayed. The grooves of childhood— both mine and my father’s— are being carved here. (Why do I use the passive voice? Am I not myself doing the carving— with a pen??)

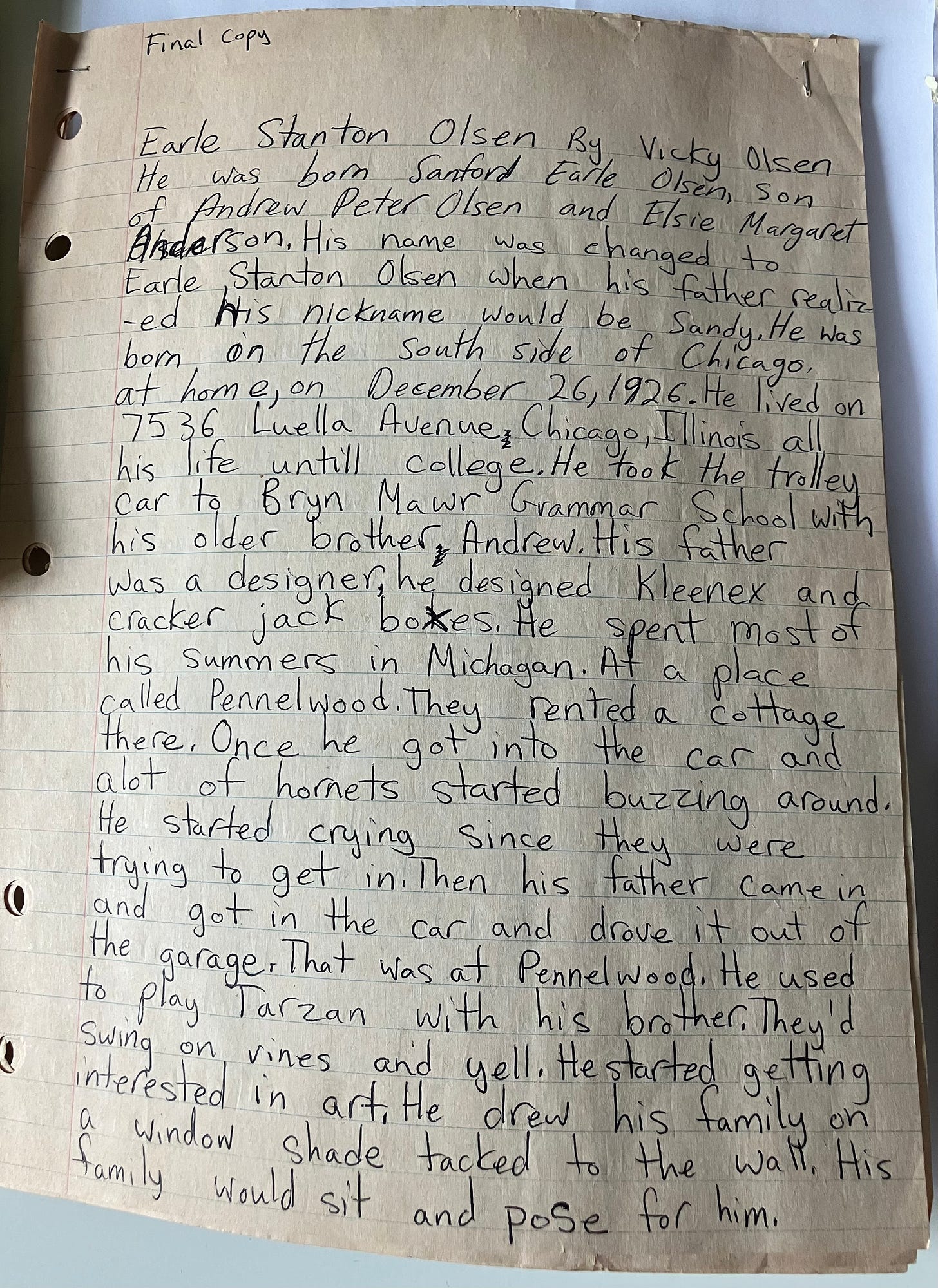

A year after I wrote that piece about my father I switched from my local public school to Bank Street School for Children, a private progressive elementary school. Is it too much to see that impact on this next piece of writing? My mother’s biography has no draft or “final copy.” It begins with a bang— a “believed to be haunted” house and some vivid dialogue (exclamation point!). It too has no paragraph breaks. It has more run on sentences, more misspellings (like Redding and Abler for Reading and Ambler in Pennsylvania), more theres for their. There are words crossed out and subjects dropped. But there’s much more attention to feelings. My mother is “worried and scared” on page one, then reassured. She is “very frightened” on page two when she moved homes, then the next move became “an adventure!” On page three “she made a important decision to go to social work school, to become a social worker.” I am starting to prioritize— and I am attuned to my mother’s emotions in ways that I wasn’t to my father’s. Perhaps he didn’t share them with me.

Both biographies taper off as the family dissolves but the similarities and differences intrigue me. In each, my parents’ separation is the next to last sentence. In each, the subject of the biography is an active agent: my father’s story concludes: “In 1972 my father got separated from my mother. He got a house is Greenport, L.I.” My mother’s story concludes “1971, she got separated from my father. 1973, got ears pierced!!” All those “gots” feel like a passive voice, though in each case there is a different actor. Reading this now, my confusion back then seems evident. Even now I find the dates hard to organize in my head. I still wonder whether my parents split up in 1970, 1971, or 1972, when it should be easy to find out, then remember.

Although both pieces seem clearly written for school, only my mother’s biography has any teacher’s feedback. At Bank Street, we called our teachers by their first names and there were no grades. I had two favorite teachers there, Michael Cook for my last year in sixth grade, and Josh Robison1, for two years of fourth and fifth grades. Josh commented on this piece in blue marker:

“This is a really interesting report— I think you should try to write in complete sentences — but your reporting is really fine. Thanks — Josh.”

I delight, now, at those dashes that seem to undermine his pointer about complete sentences but it is quite true that my mother’s bio devolves into a list of years and fragments. That last line about her getting her ears pierced has always stuck with me. I wonder if I didn’t want my parents’ separation to be an ending, so in both pieces I tacked something on after it.

Overall, those pieces hold up fairly well. Reading them as a teacher myself, I’d say I had a pretty good sense of drama and an admirable attention to specific facts and details. The fact that I wrote them at all seems so telling—that child was a proto-biographer, proto-memoirist, proto-storyteller. She was already me.

Thank you so much for reading! I appreciate likes, shares, and reposts. And I’ll respond to any comments —

Josh Robison came from a musical family and married the conductor Michael Tilson Thomas in San Francisco ten years ago. That’s the last news I heard of him. I kept up with Michael Cook for many years after leaving Bank Street and went to his memorial when he passed away in 2011.

This is so interesting -- and how great that you kept those journals, even if you don't want to read them (as stated at the outset...) I was struck by how your mother's own voice came through to me (through you!) in her bio. She must've also been a good storyteller!

Wow. From little seeds… I don’t know, there’s some metaphor here about growing into who we are, and how the earliest versions of ourselves manifest in later life. Amazing to be able to look back and see the seedlings.