Name Games

Etymologies and patronymics in family history

I just started a series of posts on my search for my father’s paintings. But this week I got pulled into two Substacks I subscribe to with posts about naming (see the Resources below). One of my delights in Substack is these serendipitous discoveries, and I like to make opportunities for conversation in Comments. So I’m detouring from the paintings this week to excerpt a piece of my memoir about family names…. BTW, speaking of names, I want to clarify that I avoid naming the living people in my private life in these posts. I’ll use initials as needed, though that’s particularly ironic in this piece about names.

In the 1970s my family lived vertically in a twelve-story building on Riverside Drive in New York City. There was a brief period when we three Olsen sisters would take the elevator down two flights to play with two of the three Anderson sisters. “Son of Anders,” I remember saying to my Dad. “Why don’t we have a name like that?” (Clearly I didn’t know then that Anderson was in fact one of our own family names. I later learned that “names like that” were called patronymics, after the father.) He explained, “We do. Olsen means son of Ole.” Since I knew no one named Ole, I hadn’t even recognized it as a name. Besides, the -son in their name was hidden as -sen in ours. Later that slight difference meant a lifetime of spelling out O-l-s-E-n, or specifying “Olsen with an e.” It was a little less common, maybe. Like my father’s name: Earle with an e.

Yet we were emphatically a family with no sons. Three was quite an abundance of daughters and I was never sure how much my parents had hoped for a boy. It seemed impolite to ask, one of the many things we didn’t talk about; bodies, money, and religion were on an official list of taboo topics, but there were plenty of unofficial ones. I knew they had chosen the name Eric for each baby, which would give that imaginary son his father’s initials. My grandparents Andrew and Elsie had named their first son Andrew Peter Olsen Jr., but there would be no Earle S. Olsen Jr. or Andrew P. Olsen III.

Later, when I learned of other naming traditions I imagined being called Victoria Earlovna in Russian, or Earlsdottir in Icelandic. My father could have been more accurately called Earle Andrewson. He inherited patronymics on both sides, being a son of Andrew Olsen and Elsie Anderson, but that was actually part of a family story I’ve mentioned before: Anderson wasn’t his mother’s biological family name because her father was adopted. Elsie’s father had been born Henry Philip Galvin to an Irish couple in Chicago. Henry’s father was “lost at lake,” a particularly poignant description for marine deaths in the Midwest, and his mother died in the Great Fire of 1871. Henry and his sister Lizzie were adopted by a farmer named Anderson in Indiana (or downstate Illinois?) who changed their name. (Maybe. Versions of these stories have cropped up in different arms of the family but no one has confirmed any of it.)

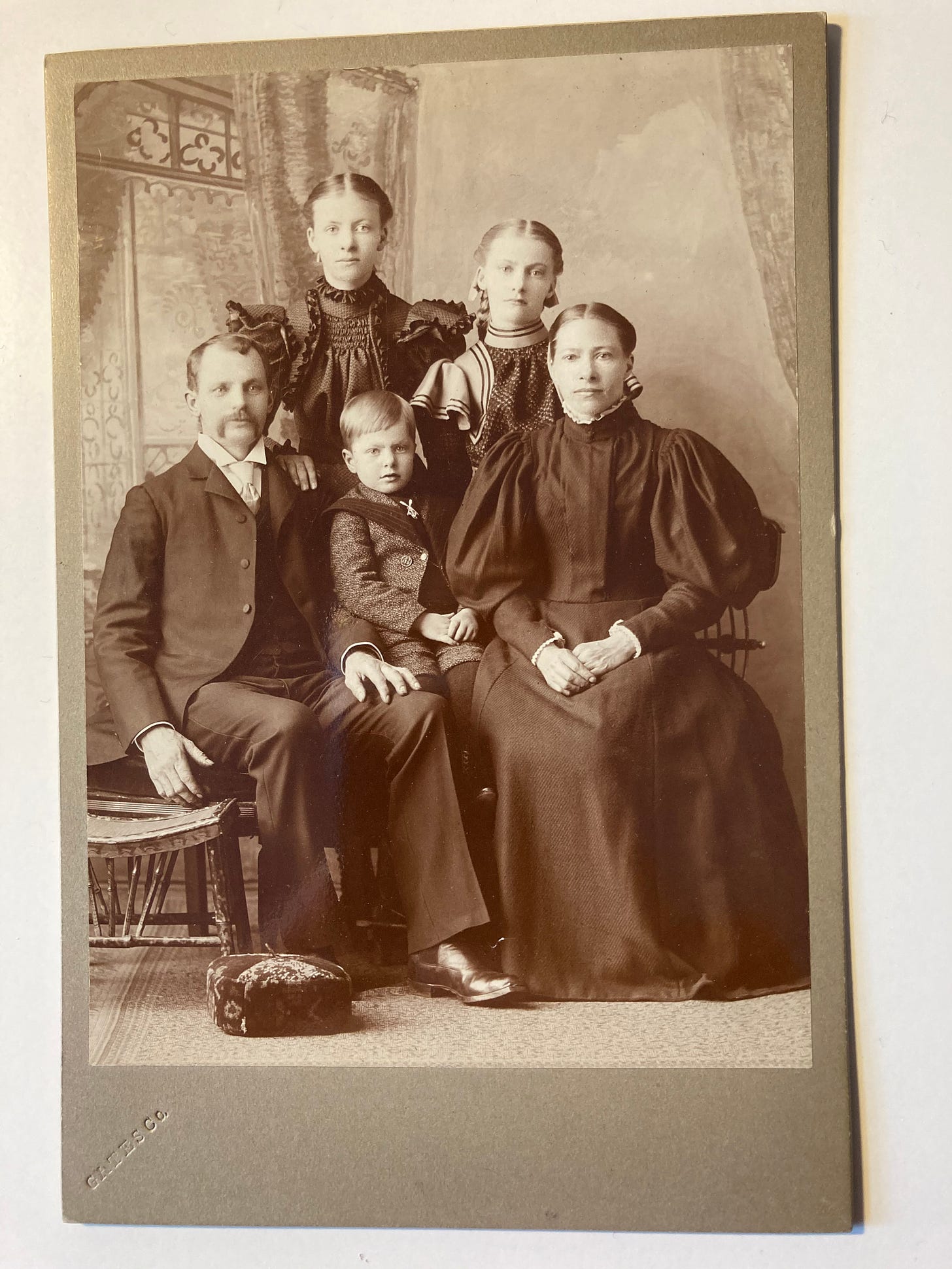

After my father passed away my sisters and I found family photo albums in his attic, including studio portraits of his Olsen grandparents taken in Copenhagen before they emigrated. They document Andrew’s origins, and foreshadow the portrait of Earle and his daughters I began this Substack with. Taken in Chicago on Christmas Eve in 1898, one is a classic studio portrait—the kind that documents respectability, complete with a faux backdrop of curtains and an ornamental window. What appears to be a small tapestry footstool lies in the foreground, a sign of gentility. The family is dressed for their parts: my father’s grandmother Karen in a mutton-sleeved dress, his grandfather Hans in frock coat and handlebar mustache, and the two teenage girls in their ruffled dresses. The eldest, Anna, rests one hand on her father’s shoulder, while May, standing next to her, loses both arms behind her mother and shadows. It’s an unnerving illusion, almost predicting her disappearance from the family; she will die of influenza in 1904. Anna lived long enough to dote on her nephews but never married. Family photos like these visually represent something about who occupies the central space in the group. Here it is not the patriarchal father Hans, but my grandfather Andrew, the only son, ten years younger than his sisters. That boy is the center the family orbits around. My father Earle would occupy that space in our 1970s family portrait, but he had no sons of his own.

The family albums provide the sort of facts (names, dates, cultural clues) that define a life. One can label the figures “industrious Hans,” “stern Karen,” or “dutiful Anna,” but they have no dimensionality. The photos attest to the immigrant family’s successes: their prosperity, stability, and health. They owned a home and a car, funded by Hans’s work as a skilled iron molder. In later photos Karen and Anna wore aprons and frumpy sack-like dresses with big ruffles. They were never stylish like my grandmother Elsie with her little hats and neat gloves. It’s easy to idealize family photographs like these: we see our relatives in a moment suspended from the rest of their daily lives. We save the ones that make us look the best, or present a certain desirable impression. Photo albums package families.

Between the births of their two sons my grandparents lost an infant daughter. She was named after Elsie Marguerite, but the spelling varies. On her birth certificate the child was Margaret Jane. Later I found MARGUERITE JANE 1925 inscribed on the short end of the family tombstone in Oak Woods Cemetery in Chicago’s South Side. Names were very important in my family, but no one was named after Elsie or Andrew. It seems clear why my parents didn’t choose Elsie, a name now most associated with Borden’s dairy cow, who debuted in 1936. Both of my sisters originally had birth certificates for BABY GIRL OLSEN. Our parents filled in the names later and never gave them middle names.1 My husband has no middle name either, but he tried on several as he grew up: first Skip, then Keith, after The Partridge Family.

Unlike some of my friends, who experimented with their given names, I never desired another name because my parents had bestowed upon me a perfect one. It was long, elegant, historical. It was easy to spell and pronounce, or translate into other languages. It was familiar but I never had to be Victoria O. because there were too many Victorias in the room. It was a queen’s name. And best of all, it meant “victorious.” In Latin! If ever a name heralded great things, it was mine. My sisters were almost as lucky, also with royal names. Together we were an impressive lot, representing the power of western culture— Roman, Christian, Anglo-Saxon. We were a female triumvirate when our mother called us for dinner in one long exhale.

I was fine with being Vicky (except when misspelled Vicki), but when I entered the academy I reclaimed Victoria. It was too good not to use, especially since I was actually a Victorianist. My name had become my destiny; it was a name to live up to. Except it was really the other way around: it was *because* my name was Victoria that I first started reading Victorian novels as a child. I read Cecil Woodham-Smith’s biography of Queen Victoria. I read Alcott, Bronte, and Eliot (and Austen, though she was a foremother). I expected to name my daughters “Charlotte” or “Cassandra” or “Amelia.” Boys’ names were much more boring so I didn’t really plan for sons.

To name is to control, as those British imperialists and European explorers knew well. To name yourself is to claim power, to begin to grow up. My sisters’ and my first efforts at naming reflected our youth, and our parents clearly gave us free rein: we named our cats Pokey and Cato (short for Cat-Olsen). In elementary school my best friend and I wrote long family sagas in installments; the best part was always naming the Cast of Characters. I finally had a chance to name a real person in the 1990s. I was living in San Francisco as a newly-married graduate student, grappling with my transition from promising academic to stay-at-home mom. In June 1994 I submitted my dissertation and earned my Ph.D. A month later my first child was born. My husband vetoed my most extravagant literary names and we settled on a three-syllable Hebrew name that went well with our two-syllable last names. That fall I went on the job market and ended up with one interview at the only hiring convention for tenure-track jobs in my field. The trip there in December was a haze. The baby wasn’t sleeping and neither were we. I remember laughing with my husband when the toothless baby lunged for a hot dog. I remember little about the interview; I never had another one. Victoria-the-Victorianist had not been enough after all. A name is only a starting point, a claim without evidence. (I became a biographer instead, and eventually a writing teacher, so I did get a happy ending.)

In 1998 my husband and I had a second child and gave them a Latin name, also three syllables. But again it turned out that a name was not a destiny. That child renamed themselves with their initials, and ditched their cis-pronoun. They are creating their own character and writing their own story.2 My own much-loved name is now an embarrassing sign of historic imperialism— literally a sign of conquest on public places all over the world. A name is a flag planted in the earth that says “I am here.” One’s name is one’s label, the external representation of the internal essence. It is like a brand, or a package. Names package people.

I see now that this excerpt is longer than my usual post, though I’ve cut it down from the original. I cut out some actual names, for example, and added some explanations you would need that readers of the memoir would already know. This section appears early in the book and I use it to introduce a familial cast of characters: my grandparents and then my great-aunt (who was my main source of information about them later on). Then I transition into a section on brand names (you can see that coming in my conclusion about “packaging.” My grandfather Andrew was a commercial designer and my family memoir covers both his design career and my father’s fine art career. I’ve written one post about Andrew’s careeer already but promise to write more about branding and product names in the future, especially Kleenex and Kotex, which were Andrew’s main claims to fame.

Thanks for reading this far! As I’ve said, I’ll eventually turn on paid subscriptions, but in the meantime, enjoy the exercises and resources here and in my archived posts. And special thanks to Kathleen/Kathrine/Kate Motley and Jeff/Jeffrey Streeter for prompting this piece!

Exercise: Dig into the etymology of the names in your family and try to untangle some of the influences and associations. Where does a name fit and where might it mislead? Where is the influence clear and where is it hidden? Feel free to share any stories in the comments.

Resources:

KateMotleyStories’s recent post on What’s in a Name inspired this one. She writes entertainingly about how her name evolved over generations, and a link led me to…

Jeffrey Streeter’s Changing Names, part one, about how his name has evolved internationally. I only just now realized that there’s a part two! so be sure to read both fascinating pieces.

My middle name, Clark, was chosen to honor my mother’s Scottish grandmother, but now feels like a reference to Andrew’s biggest design client, Kimberly-Clark. As a child, I wanted to change Clark to Clara because I hated having a boy’s name (and because of Heidi…).

They are an artist and drew the small portrait of me that I use in my profile and logo for this newsletter. :)

Thank you for the mention Victoria, much appreciated. I enjoyed your article. Of course, the name Victoria became popular because of Queen Victoria - who was christened Alexandrina Victoria. Her German mother was called Victoria, but it was an unusual name in Britain at the time.

This is lovely, I so enjoyed reading it, Victoria. And thank you for the kind mention.

I'm really pleased to have found your newsletter!